Dr. Twede is an internationally renowned thought-leader, an eminent researcher, and an inspirational educator. She embodies an all-too-rare combination: someone who is not only knowledgeable but also is generous in sharing that knowledge.

SA: You were a research assistant to the late Dr. James Goff, founder of the Michigan State University School of Packaging. Please share an enduring lesson learned from him.

Dr. T: Dr. Goff envisioned the contributions that packaging education could make to industries and to societies. Packaging graduates will understand the complexities of packaging decisions and will be able to critically evaluate the economic, environmental, and

social effects. Graduates will understand that they are not limited to any single material and will be able to compare packaging systems on an objective basis. Furthermore, Dr. Goff’s research emphasized the reduction of unnecessary packaging. His contribution to fragility theory

led not to more cushioning, but to less, by decreasing the fragility of sensitive products.

SA: As an expert in the economics and performance of packaging, what is your advice to brand-owners regarding how to manage the trade-offs between those two aspects?

Dr. T: Follow the money, because packaging performance can increase sales and can reduce the cost of advertising, logistics, damage, and disposal. Decisions should be based on long-term strategy as well as short-term problem-solving.

SA: Today, globalism and supply chain management are top corporate concerns, but for decades prior, you were championing the role of packaging in logistical systems. How good a job is industry doing in leveraging packaging in that area and what can be done to accelerate progress?

Dr. T: Supply chain management gives us the tools to leverage packaging. By managing a supply chain as a system, we are better able to achieve the vision of Dr. Goff and of Dr. Bowersox, the legendary MSU logistics scholar: that packaging is a tool to physically and virtually integrate supply chains.

The industry has come a long way towards integrating packaging and physical logistics. An example is that the days are gone when the corrugated box industry dictated the form of a shipping container.

Transportation is the highest cost in most logistical systems, and packagers have most

significantly reduced transport cost by reducing cube. We now consider pallet patterns during the product/packaging design phase. Companies like IKEA employ cube reduction as a competitive advantage and go so far as to vacuum-pack pillows to reduce transport cost.

Packaging postponement has also reduced transportation cost for visionary companies like Hewlett Packard and Gillette. Likewise, warehousing and material handling costs have been reduced through packaging standardization.

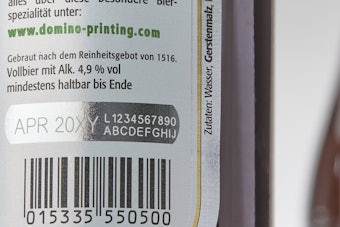

Packaging also plays a role in streamlining information management with the use of automated identification, like bar codes and RFID. By substituting information for inventory, packaging can make supply chains more responsive and lean.

But there is still a long way to go. To paraphrase a certain well known Hollywood blockbuster, space is the final frontier. Carriers’ dimensional weight pricing policies add further incentive to reduce the cube of packages. That applies to logistics, in general, and especially to e-commerce. And I don’t know why more e-commerce retailers don’t understand that truth. The last pillows I bought, from a U.S. retailer who will go unnamed, arrived in a box twice as big as both pillows combined, wasting packaging materials and transport cost.

SA: What about returnable shipping containers? Although they are typically associated with industrial goods, what are some examples/opportunities for their use with consumer packaged goods?

Dr. T: Reusable shipping containers are rarely used for consumer goods because of the complexities of the supply chains and the diversity of consumer package configurations. Most consumer goods don’t move fast enough to justify the higher cost of sturdy reusable containers, and their supply chains lack the control necessary for efficiently returning them for reuse. The wide variation in the size of consumer goods and packages is effective for product differentiation but is not compatible with standardized container dimensions. And there are no third-party players that have demonstrated a capability/willingness for investing in, pooling, and redistributing containers.

The best we have is the pallet industry with standard 48” x 40” GMA pallets. The reasons for their success are standard dimensions that can accommodate a number of pallet patterns, the low cost of wood, and their ubiquity, which facilitates a market for buying used ones to resell to a new user.

There are notable exceptions. Consumer goods, like bread, soda pop, and Fritos, which are directly delivered to stores, are the largest users of reusable containers because the vendors control the reverse logistics, picking up empties as they stock store displays.

Some retailers, like Kroger, require reusable plastic crates (RPCs) for fresh produce, and contract with a third-party that owns and controls the logistics. RPCs are up to 10 times more costly than the equivalent corrugated box/tray, but the savings accrue over time.

By far, the most prevalent reuse is of fibers. Corrugated fiberboard boxes are the most recycled form of packaging for technical, economic and logistical reasons. It is a good reminder that there is a demand for reusing shipping containers and their materials.

Frito-Lay even reuses relatively inexpensive corrugated fiberboard boxes, finding that they are capable of being reused up to 10 reuses. It evidences the strength of regular slotted containers (RSCs) and the potential opportunities for their reuse. Citing another example, the MSU campus reuses the corrugated boxes in which it receives food for the cafeterias, by making them available to students for packing to move back home, and has developed a simple sorting system to facilitate it.

SA: Please share some of the insights and hopes gained from your decades of involvement in projects aimed at using packaging to reduce world hunger.

Dr. T: In the 1980s through 1990s, I worked with the U.S. Food Aid Program, where our emphasis was on delivering American food to needy recipients in some of the most challenging logistical systems in the world. In this case, our emphasis was on protecting the food at a low

packaging cost. We developed test methods to judge and compare the protection afforded by packages and we developed damage feed-back mechanisms to track actual loss and damage. As part of this effort, I learned about the importance of reproducing damage in laboratory tests and tracking performance through a damage claim system that can assist packaging decisions.

But I also learned that the development of a country’s own packaging supply industry is key to reducing world hunger. Recent USAID programs develop a country’s own agricultural capability, including ways to package indigenous food products, in order to improve a country’s internal distribution and export capability. Packaging education can play a vital role. A good example is Thailand, where our alumni have developed university programs to facilitate its growing packaging industry. The packaging industries in China and India have developed in tandem with university and national packaging research institutes. Such initiatives are also underway in African and South American countries, many of which are facilitated by the International Trade Commission.

SA: Your most recent research has been on the history of shipping containers. Are there some insights that you would like to share?

Dr. T: 4000+ years of packaging progression reveals some universal functions of shipping containers. We packagers of today share the same concerns as ancient packagers who developed baskets for gathering, two-handled storage jars called amphorae, barrels that colonized the world, and shipping sacks made from various materials. And so it goes, right up to modern-day wooden and corrugated boxes, pallet loads, and ocean containers.

Although packaging forms and logistical systems have changed over the millennia, the

functions performed by packaging have remained constant. This is an inspiring message for those of us who work with logistical packaging, making us heirs to a long tradition of delivering the goods.

The time-tested, universal design factors include:

- geometry to facilitate lifting, carrying, storage, and stowage for transport;

- protection and containment to extend shelf life and prevent damage;

- economics to minimize the cost of packaging;

- reuse and/or recycling to conserve resources;

- relationships between associations of transportation carriers and packagers, including packaging education;

- standardization of containers to facilitate trade; and,

- identification to communicate origin, quality, and net contents.

SA: With Michigan State University bestowing more packaging degrees than any other institution, how does MSU ensure that its curriculum is responsive to the dynamic needs of industry?

Dr. T: The MSU School of Packaging’s Industry Advisory Committee first met in 1953. They approved a new curriculum that included seven packaging-specific courses: Principles of Packaging; Wood & Paper Technology; Packaging Materials; Industrial Packaging; Consumer Packaging; Packaging Cost Analysis; and, Packaging Problems, plus a Senior Seminar that included 12 weeks of practical experience in industry. Over the past 65 years, the curriculum has changed, but we still have an active Industry Advisory Committee (IAC). They and the MSU Packaging Alumni Association (MSPAA) provide strong support and meet with us regularly. Over recent years, their advice has led to an increased emphasis in computer-aided design, financial evaluation, and sustainability.

In lieu of an academic accreditation body, such industry advice is common for most packaging education programs. Last year, as part of our strategic planning process, they helped us with a major curriculum review. We started with expected learning outcomes--the skills that employers expect our graduates to bring to the workplace. In response, the IAC and MSUPAA recommended the desired technical, economic, and communication skills. They additionally emphasized differences among science, management, and engineering, and the need for a rounded perspective about packaging, to be delivered in a freshman seminar course.

Speaking of freshmen, Packaging is now a true 4-year curriculum, unlike the old days when most students transferred in from other majors as juniors or seniors. Today’s incoming students have heard about packaging as a major and are aware of the status of MSU’s program. We call this the uncle-and-aunt effect, because, although a few of the freshmen are sons or daughters of alumni, many more have heard about us from aunts and uncles, in addition to unrelated graduates. This gives students more time spent within the curriculum to develop their packaging expertise.

As a result of mapping the student learning outcomes to our undergraduate curriculum, we are now proposing three paths to graduation: packaging science; packaging value chain; and, packaging engineering. More courses are required from related departments, like food science and business. We have added new packaging courses to help students better understand the industry and to get more practice with the design process. And we are implementing an outcome-assessment review process to track improvements.

And, along with the rest of the university, we are also responsive to industry’s demand for sports talk. Those Spartans play great ball! Go Green!

SA: And on that public service announcement, we’ll call this interview a wrap. Thank you, Dr. Twede.

____________________________________________________________________

Sterling Anthony, CPP, is a consultant specializing in packaging, marketing, logistics, and human-factors. His contact information: 100 Renaissance Center, Box-176, Detroit, MI 48243; telephone 313-531-1875; [email protected]; www.pkgconsultant.com