Contract Packaging magazine developed this online survey, conducted with assistance from Packaging & Technology Integrated Solutions (PTIS), a consultancy that helps companies to better integrate packaging into an overall management strategy, and Global Sourcing Solutions (GSS), a company that offers purchasing and supply chain consulting and staff development training services.

This survey represents the views of both large and small companies—and both buyers and suppliers of contract packaging services. Respondents are from companies with more than 2ꯠ employees and from companies with fewer than 100 employees.

Approximately 18% of the total respondents were from companies with more than 2ꯠ employees. Roughly 7% were from organizations with 1ꯡ to 2ꯠ employees. Almost 10% were from companies with 501 to 1ꯠ employees. Another 22% were from organizations with 101 to 500 employees, while 44% were from companies with 100 or fewer employees.

Contract Packaging acknowledges the contributions of PTIS principal Brian Wagner and GSS principal Lowell Hoffman. They assisted in formulating the survey questions and interpreting the results.

Materials costs and energy prices are escalating. How are these increases altering the relationship between buyers and sellers of contract packaging services? Conversely, does the type of existing relationship impact the ability to effectively manage cost increases?

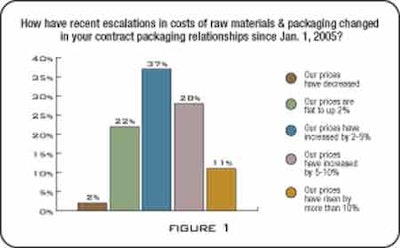

A whopping 39% of respondents to a targeted survey on contract services say that recent increases in the costs of raw materials and packaging have, in turn, increased the cost of their co-packing projects by 5% or more since January 2005. (Fig. 1).

But an analysis of the results also makes it clear that although contract packaging has grown significantly over the past 10 years as an industry in the United States, many of the rules are still being written. Still, in the majority of cases today, the buyer wields more leverage than the supplier of services in negotiating materials costs.

Contract Packaging invited readers to complete its on-line survey in May 2006 and received about 200 responses. Significant results from the data and analysis show:

Top-line findings

• About 57% of respondents say the buyer and the service provider share equal responsibility for controlling costs in their contract packaging relationships (Fig. 2). Otherwise, the buyer takes responsibility slightly more often than the service provider.

• Approximately 51% of supplier respondents and 50% of buyer respondents say increases in energy costs are prompting costs to be included in periodic negotiations (Fig. 3). And 29% of the buyers claim that energy costs are being passed through to the buyer, according to contract provisions, while 25% of the suppliers say they are absorbing the higher costs.

• Asked to what extent price changes resulting from underlying raw materials and packaging cost fluctuations are covered by specific contract language with “defined pass-through computations,” 61% of respondents say price changes are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. The percentage remained consistent with both buyers and service providers.

• A clear cause-and-effect relationship exists between rising prices and the buyer’s response of changing or adding suppliers (Fig. 4).

• Interdependency—some call it partnership—is broadly recognized as a solution when supply chains tighten. For example, 62% of buyer respondents say that joint collaboration on supply management has increased as a result of disruptions in material supply changing the buyer’s role in supplying critical packaging materials (Fig. 5).

• Many of the buyer responses were from companies with 2ꯠ or more employees while most of the supplier responses came from companies with 500 or fewer employees. This disparity suggests that the purchasing leverage still often resides with larger consumer products companies. When the buyer and supplier don’t share cost-controlling responsibility equally, the buyer is twice as likely as the supplier to have the control.

The survey generated 59% of its responses from buyers of contract packaging services and 41% from service providers. The percentages presented in this article, unless otherwise noted, represent responses in total from both buyers and suppliers.

The format of the survey was developed with a supply chain viewpoint in mind. The objective was not only to determine the impact of cost inputs on current pricing but also to assess existing buyer-supplier relationships and then to gauge how these relationships are changing as a result of price pressures.

Price impacts on co-packaging relationships

Price escalations have been significant and affected buyer-supplier relationships. Escalating energy costs are bringing about higher operating costs across the supply chain for consumer packaged goods. Prices, in turn, are rising for raw materials, packaging plant overhead, and transportation. For consumer packaged goods companies, these factors could reduce profit margins. Anecdotally, contract packagers are saying that rising costs are routinely an issue in pricing negotiations for their services.

Fig. 1 plots the degree to which rising energy and materials prices are factoring into the relationship between buyers and providers of co-packing services. Significantly, 39% of the respondents indicate that their prices have increased by at least 5% since the beginning of 2005—and 11% say the increase exceeds 10%.

Lowell Hoffman, principal with Global Sourcing Solutions, finds that troubling. “In most cases, the buyer is setting the minimum-maximum level, which has little to do with service and can add unnecessary costs,” observes Hoffman, a former purchasing and materials executive for two decades at National Can Corp., Kraft Foods, and Colgate-Palmolive. “Suppliers are often in the best position to suggest inventory replenishment policies, as they best understand their ability to respond to changes in demand.

“One-third of the survey respondents jointly manage inventory policies. That reflects a willingness to understand both the buyer’s changing requirements and the supplier’s commitment to provide service.”

Other impacts

Tight supplies of energy resources and raw materials reflect the current state of co-packing relationships in other ways, the survey finds. When asked how order-to-fulfillment cycle times, expectations, and results have changed, 43% say they are satisfied with no changes while 25% say they have increased their tolerance for delays—evidence of a comfortable relationship, Hoffman concludes.

However, the results show that team negotiation, when led by either purchasing or other departments, correlates with greater expectations in cycle time reduction.

A look at Fig. 3 shows how increases in energy costs have affected co-packing contracts. About 50% of buyers and 51% of suppliers say the costs are included in periodic negotiations. After that, the costs increases are most often (29%) passed through to the buyer, according to contract provisions. About 25% of the time or less, suppliers shoulder the higher energy costs.

“I found it of interest that only 26% had included energy costs changes in the specific price adjustments defined in the contract,” Hoffman observes. “This may well be appropriate as for many contract packaging operations, energy would be expected to be a minor overhead cost rather than a significant process cost. If energy costs were in the MRO (maintenance, repair, and operating cost) category, I would expect the supplier to absorb this cost. As a buyer, I would be reluctant to include energy costs in periodic negotiations if it was not a specified direct and variable cost.”

The value of interdependency

Brian Wagner, partner at Packaging & Technology Integrated Solutions, has more than 20 years of experience in supply chain management and innovation management for companies such as Kellogg’s, Sara Lee, and Burger King. He is a big believer that collaboration brings the best results in successfully navigating the supply chain.

“It seems fairly consistent from the data that when an individual purchasing professional tries to negotiate on their own, they don’t come out as well as if they had collaborated with others,” Wagner notes. He points to survey results showing that increasing raw materials costs are bringing about more collaboration across the board between the buyers and the suppliers of both services and materials when negotiating supply management issues.

Both Wagner and Hoffman find that the survey data support the importance of active collaboration between buyers and sellers through the involvement of stakeholders, whose own success depends upon the relationship.

As Fig. 2 shows, 57% of the time, the primary responsibility for controlling costs on contract packaging relationships is shared between buyer and supplier. About 23% of the time, the responsibility rests with the buyer and 20% of the time, the responsibility falls primarily on the supplier.

Further analysis of the data indicates that:

• When buyer and supplier share the responsibility for controlling costs, joint collaboration on supply management has the best chance of increasing, 62% of the time (Fig. 5). Pleasing to Hoffman was that a significant number—59% of respondents—say that overall, joint collaboration on supply management has increased.

• When buyer and supplier share the responsibility for controlling costs, increases in energy costs are mostly likely to be included in periodic contract negotiations, 56% of the time. In a shared-responsibility relationship, it would be difficult to ignore a supplier’s introduction of energy costs into negotiations. “I view this response as good evidence of the co-dependency observation that’s evident in the survey data,” Hoffman says.

• About 31% of respondents say that prices are flat to up 2% when the purchasing manager consults other stakeholders in contract negotiations. But 36% say that prices rise 2-5% when the purchasing manager handles pricing negotiations alone. Overall, only 26% of the time does the purchasing department alone handle negotiations for changes in contract pricing on the part of the buyer. In more than half of relationships (54%), the purchasing department consults other stakeholders, or these other stakeholders participate on the negotiation team.

In addition, the buyer is mostly likely to be willing to fund capital improvement projects—nearly 20% of the time—when the purchasing manager leads a negotiation team or consults other stakeholders during negotiations for prices changes. The buyer is at least willing (2% of the time) to fund capital improvement projects when the purchasing department handles negotiations alone for changes in contract pricing.

“This data, to me, is evidence of the importance of team-based relationship management,” Hoffman says. “If I am the buyer, I have to get price. I may not have anyone on my team who understands the overall process and can see the opportunity to invest in a more productive machine, a larger cavitation mold, or new technology.

“Additionally, as a buyer, I may not have input into my own company’s capital investment budget. Inclusion of operations or engineering managers on my negotiation team may well make funding of capital improvement projects with my supplier a frequent event.”

The survey results spell out a clear correlation between disruptions in shipments of packaging materials through the supply chain and the tendency to change or contract additional suppliers. Data in Fig. 4 point to what happens in cases of rather significant price jumps. When prices increase 5-10%, 30% of respondents say they add a new backup supplier, 26% significantly rethink their supply strategy, and 19% change suppliers.

When prices rise 10% or more, 40% of respondents say they significantly rethink their supply strategy, 35% add a new backup supplier, and 15% report multiple changes in suppliers.

“What I see is that when the going gets tough, the tendency is to go back to what I call Purchasing 101, or business as usual,” Hoffman explains. The numbers support his contention. About 71% of respondents overall say they “test the market” with more frequent bidding. In addition, 42% make multiple changes in supplier relationships and bring additional suppliers on board.

“These are natural outcomes but may reflect tactical and short-term responses to strategic issues.” Hoffman notes. “That so many respondents mentioned ‘significant rethinking of supply strategy’ was encouraging. Tactical responses may solve today’s supply issue: New strategies should manage tomorrow’s supply requirements. It is also quite possible that our respondents have learned that the ‘reduce supply base’ mantra of prior years’ so-called strategic sourcing initiatives may have resulted in too small a supplier base or suppliers chosen on the basis of bid price rather than a best supply chain solution.”

Wagner observes, “It is interesting that as prices have increased, the buyers have reacted by going in a number of different directions. Companies need to do a better job of anticipating marketplace changes and building contingency plans into their contracts.

“It isn’t just about the bottom line,” Wagner adds, “but also the top line and driving innovation. When material and energy costs rise, a lot of purchasing attention tends to go to cost savings and cost cutting. It’s important that we don’t forget about supply value relative to innovation and growth initiatives.”

Moving forward

The value of collaborative negotiating teams is recognized and put into practice only a small majority of the time, and this exclusive survey shows there’s still significant room for improvement. Buyers should ensure that the supplier relationship is a team event. Whether the purchasing manager or others lead a team, it is imperative to include stakeholders in establishing requirements, participating in negotiations, and evaluating metrics produced by the relationship.

Suppliers can improve their position by actively seeking to understand their customers’ markets and strategies, and by offering their own resources to improve competitive position. Options include inviting customer teams and content experts to provide cost- and process-improvement suggestions.

As purchasing departments develop their strategies, the results of this survey may help them to create more collaborative strategies in building contingences into their contracts, anticipating change, and remaining flexible. [CP]

Shortcomings in areas where interdependency could work

Real advances in cost reduction and supply chain management become possible with a willingness to use human resources to impact the culture and processes of supply chain partners, says Lowell Hoffman of Global Sourcing Solutions.

Although evidence of collaboration scored big in many areas of the survey, it was found wanting in others:

• Only 33% of buyer respondents say they have initiatives in place to become more involved in their suppliers’ internal processes in order to reduce costs.

• Just 10% of buyers are willing to fund their contract packager’s capital improvement projects to reduce overall costs.

• Only 21% of buyers send value-improvement, or “Six Sigma,” teams into supplier plants.

• Just 2% of buyers place employees within the supplier’s plant as an in-house representative involved in planning, scheduling, logistics, or product development.

Jim George, Editor-in-Chief of Contract Packaging magazine, helped shape the concept and scope of this study.