“None of the bio-based plastics currently in commercial use or under development are fully sustainable. …Some bio-based plastics are preferable from a health and safety perspective, and others are preferable from an environmental perspective.” That’s the top-line conclusion of a study published by the Journal of Cleaner Production, titled “Sustainability of bio-based plastics: general comparative analysis and recommendations for improvement.”

Beginning with the assumption that “bio-based plastics appear to be more environmentally friendly materials than their petroleum-based counterparts when their origin and biodegradability are compared,” the 9-page study takes a qualitative approach to comparing a range of bio-plastic materials, “including all stages of their life cycles (cradle to grave) to assist in decision making about the selection of these materials.” In particular, the study evaluates which of the bio-based plastics currently on the market, or soon to be on the market, are preferable from an environmental, health, and safety perspective.

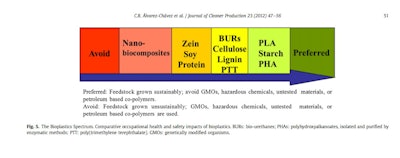

To analyze the materials, the study—conducted by the Work Environment Department and the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production, University of Massachusetts-Lowell—reviewed existing literature on their environmental, health, and safety impacts, using a Bioplastics Spectrum to visually summarize the data.

Defining and ranking bio-based plastics

One of the findings of the study was that “a consensus definition for a bio-based plastic does not exist,” adding that “a bio-based plastic is not necessarily a sustainable plastic; this depends on a variety of issues, including the source material, production process, and how the material is managed at the end of its useful life.”

In order to define a sustainable bio-based plastic, the study reviewed the ranking schemes and criteria developed in the last decade, including the Plastics Pyramid, the Plastics Spectrum, and the Plastics Scorecard. The 12 principles created by the Sustainable Biomaterials Collaborative were used as a framework to develop a definition for a sustainable bioplastic in the study and to evaluate the sustainability of the bio-based plastics from the information obtained in the literature review.

The study provided a comparative analysis for the following materials: polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs); polylactic acid (PLA) and starch; bio-urethanes (BURs), cellulose, and polytrimethylene-terephthalate (PTT); proteins from corn and soy; and nano-biocomposites.

After the analysis and evaluation, the study concludes that “some bio-based plastics are preferable from a health and safety perspective and others are preferable from an environmental perspective.” It adds, “Although advances have been achieved, fully sustainable bio-based plastics with all the highly valued properties of conventional plastics for all types of products are not yet available.”

The resulting Bioplastics Spectrum places nano-biocomposites at the “Avoid” end of the spectrum, while PLA, starch, and PHA fall on the “Preferred” end. A table of the environmental and occupational heath and safety hazards of bio-based plastics indicates that nano-biocomposites (cellulose and lignin) use a process that has relatively high energy and water requirements, emits pollutants to air and water during the kraft process, and involves unknown potential toxicity issues related to incineration, composting, and recycling.

Regarding PHAs, PLA, and starch, the study says “although there are some occupational hazards in their production, these hazards were considered lower than that of the other bio-based materials.”