Getting the consumer to try a product is a daunting challenge for any CPG company. And to a great extent it's the package that has to hit on all cylinders if there's to be any hope of success. Accordingly, the term "shelf impact" should refer not only to the package's ability to be noticed but also to its ability to influence purchase decisions─that is to say, to perform as the silent salesman at what's been dubbed "the (initial) moment of truth."

A company, in its attempts at seduction, should acknowledge that consumers have a mild schizophrenia regarding trying something new. On the one hand, the untried entices, stokes curiosity, and appeals to the desire for something better. On the other hand, the untried, because it represents the unfamiliar, poses risk and triggers caution. The package has to be salesman and psychologist, as it were, emphasizing the product's positives while assuaging consumers' reluctance. But no matter how mightily a package labors in that regard, it can use all the help it can get.

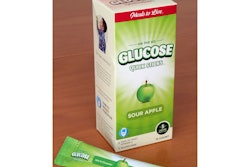

One form of help is the trial-size package. Admittedly, it doesn't have the ability to be as instantly convincing as in-store sampling; nonetheless, it's darn-sure less labor-intensive, and like in-store sampling, it implies that the company is confident about its product. It follows, therefore, that trial-size packaging won't be successful for a run-of-the-mill product, or even for a product that claims to be the first in its category, if it doesn't meet consumers' expectations. In contrast, if a product embodies a relevant difference, demonstrable by a single try, then providing it in trial-size packaging can pay full-size benefits.

Honey, I shrunk the package

The development of a trial-size package involves more than merely designing a miniature of the full-size package. Miniatures that replicate package type (i.e. bottle-to-bottle, tube-to-tube, blister-to-blister, carton-to-carton, etc.) provide the consumer with the strongest ability to recognize the full-size package, and such linkage carries over to brand recognition. But even with such correlation, replication isn't practical to the degree of miniatures looking as if they're full-size packages that have been hit with a shrink-ray. Structure is not as much the problem as is graphics; for example, a miniature bottle can have the shape of its full-size counterpart but not the space for all of the graphics. Graphics that identify brand and product category are sacrosanct, requiring that a company decide what graphics are expendable so that the miniature presents an uncluttered look. Certain promotional copy might have to go. And with products with self-defining usage (think shampoo and deodorant), directions can be eliminated.

In no way, however, is a company locked into staying with a given package type. As an example, a wide range of products (liquids, semi-liquids, powders, granular) of various full-size package types can be packaged in trial-size pouches. Such packages can be laminations that incorporate barrier layers, if such protection is required. Furthermore, pouches can be printed by flexography, rotogravure, letterpress, and lithography, for whatever graphic presentation is desired. Pouches, flexible structures that they are, also can be less expensive than rigid structures.

The aforementioned notwithstanding, pouches are not excused from the requirement of promoting recognition of the full-size package. The most bare-bones way is to adorn the pouch in the signature colors and other graphic elements of the full-size package. A step further would be a depiction of the full-size package on the front of the pouch. But no pouch option beats die-cuts for replication because those pouches are die-cut in the shapes of the full-size packages.

Shape replication also can be achieved with blow-fill-seal technology and thermoforms, which don't comprise an exhaustive list. Additionally, there are proprietary technologies and packages, obliging CPG companies to stay apprised of supply markets.

And since it's unwise these days to not factor in the sustainability of a packaging choice, suffice it to say that trial-size packages score low on product-to-packaging ratio. Luckily, the concept of life-cycle analysis affords a CPG company other areas in which to manage operations for a minimal carbon footprint.

Are you kitting me?

The concept of packaging in kit-form is simple: bundle items that are different from one another but share a kinship. The practicality of kitting has long been recognized in medical packaging wherein the various instruments and components needed in a particular surgical operation are packaged together. Kitting has crossed over into trial-packaging.

A toiletries marketer, for example, can combine a trial-size package each of several different products into a kit. Multiple exposures are the inherent consumer convenience and can be coupled with others, such as take-along convenience, in the example of a travel kit. As for how to get kits in the hands of consumers, CPG companies shouldn't always think in terms of selling. Consideration should be given to the merits of give-aways as part of a promotion budget.

Actually, decisions about distribution have to be made in all instances of trial-size packaging. Depending on variables, trial-size packages may be distributed in a variety of ways. One way is a pack-on to the full-size packages of a GPG company's other products, or for that matter, a pack-on to the full-size packages of another CPG company's products, in a co-marketing agreement. Another is as magazine inserts. Yet another is in combination with couponing. One more is as sellable items in dump bulk bins.

Let's take it outside

It's foreseeable that a CPG company might not have the equipment to run trial-size packaging and would have to enlist the services of a contract packager. In that event, there are critical contract packager/client company issues to be addressed. Will product formulation be performed at the contract packager? If not, how will the product be provided in bulk to the contract packager? What secondary-packaging operations are required? After contract packaging operations are completed, how will inventory be placed in the commercial stream and under what type of monitoring and control?

Certainly, there are a host of other questions that can be asked. Together, they underscore how critical it is to choose a contract packager not only on the basis of filling-line capabilities, but also on its ability to deliver one-stop, turnkey services, with heavy emphasis on quality-assurance (particularly as it relates to regulatory dictates), security, and supply-chain management.

It's often said that good things come in small packages. Well, so do big responsibilities. But when a CPG company has an appropriate product and puts it on trial in the right miniature package, consumers are likely to render a favorable verdict.

Sterling Anthony is a consultant, specializing in the strategic use of marketing, logistics, and packaging. His contact information is: 100 Renaissance Center- Box 43176; Detroit, MI 48243; 313-531-1875 office; 313-531-1972 fax; [email protected]; www.pkgconsultant.com.