In no area is there as much emphasis on anticounterfeiting than in the drug industry. Expect to see even more activity in this area now that the Food and Drug Administration’s February report, “Combating Counterfeit Drugs,” is out. Both prescription-only and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs will be affected.

“The Counterfeit Drug Task Force final report focuses on the prescription drug supply because that’s where we’ve seen the most counterfeiting occur,” says Ilisa Bernstein, senior science policy advisor at FDA. “The counterfeiters target higher-priced drugs and prescription drugs that cost much more than OTC drugs. However, that doesn’t mean that OTC drugs are not at risk. Consumers should be vigilant when buying OTCs as well.”

Counterfeiting is a larger problem outside the United States than within the country, but that doesn’t mean domestic products are immune to counterfeiting. Lew Kontnik is a consultant on anticounterfeiting, and he points out that in May 2003 nearly 20 million doses of fake Lipitor (a cholesterol-lowering medication) were pulled from pharmacies in the United States. Kontnik also points to fake Viagra imported into the United States from South America and Asia.

Whether the counterfeiting affects prescription or OTC drugs, the game plan laid out by FDA is to use multiple packaging strategies as a defense. As the FDA report says, there is no “magic bullet” in foiling counterfeiters. Rather, the FDA strategy aims to combat counterfeits with a multilayer approach that combines multiple overt and covert techniques along with radio frequency identification (RFID) as tactics in assuring the safety of the drug supply.

“The philosophy is that you have to keep rotating your measures,” says John Bitner, president of Bitner Associates, Inc., a consulting firm working with major pharmaceutical corporations who are addressing the issue. “With today’s technology, it is only a matter of time before the counterfeiters can figure out the system. You have to keep one step ahead of them.”

FDA in its February report on anticounterfeiting agrees. That’s why the agency plans to issue guidance that would facilitate regular changes in anticounterfeiting techniques—”rotating your measures,” as Bitner puts it.

RFID as a constant

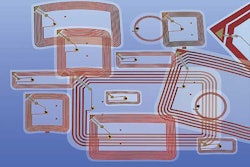

Although FDA envisions a variety of anticounterfeiting techniques coming into play, it does see one constant—RFID. The FDA report asks for RFID tags on prescription drugs at the primary package level by 2007. In essence, that strategy puts a unique serial number on each primary package at the point where it is packaged, allowing it to be tracked and traced through the supply chain from point of origin to point of use.

“The supply chain is where the product lives,” says a report from The Product Surety Center, a New Mexico State University organization that helped develop the February report for the FDA. The Product Surety Center’s report goes on to say that anyone who intends to counterfeit or tamper with product has to enter the supply chain at some point, and the ability to detect that entry through track-and-trace technology improves the chain’s security.

Under FDA’s RFID scenario for drugs, a unique electronic product code (EPC) identifier on each primary package will reveal if counterfeits have been introduced into a pallet. A check of the EPC of each package against shipping records will show which packages have been removed and which do not have the appropriate codes.

In implementing RFID as an anticounterfeiting technology, FDA wants widespread implementation by 2007. This year the agency will conduct feasibility studies using RFID on pallets, cases, and packages of pharmaceuticals. Indications from suppliers are that many drug companies are already running pilot programs to assess options.

The Wal-Mart factor

Another player in this field is Wal-Mart. The retailer wants to have RFID tags on Class 2 prescription drugs (addictive painkillers and other narcotics) as a way to further control these substances moving through its pharmacies. Wal-Mart’s timeline is more aggressive than FDA’s, and it already is behind schedule. The initial Wal-Mart deadline was March 2004, and the deadline has already been pushed back because its vendors could not meet the date.

Will pharmaceutical manufacturers be able to meet FDA’s timeline for implementation of RFID as an anticounterfeiting tool?

“The chip technology is not there yet,” says Neil Sellars of National Label Co.” The refinement of the chip technology and the limited availability of chips is a restriction right now.” Chip suppliers are focused on Wal-Mart’s case/pallet initiative right now, Sellars explains, and they are not focusing on chips for individual packages.

(Wal-Mart’s case/pallet initiative and FDA’s individual drug package goal rely on the same underlying technology, with some technical differences. The major one is tag size. The case and pallet tags are bigger, while tags for individual drugs are, at most, 1-inch by 1-inch in size.)

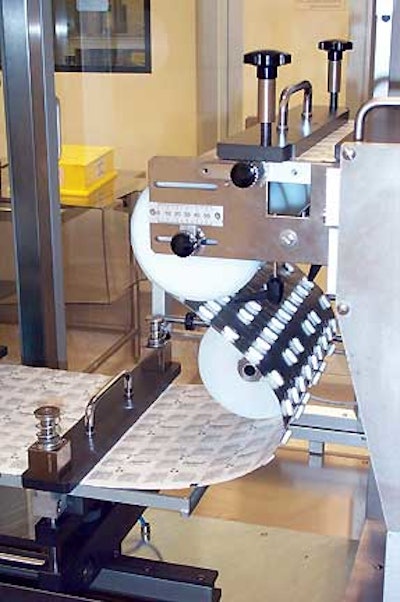

To cost-effectively implement the technology on primary drug packages, pharmaceutical companies are going to have to integrate tags into high-speed packaging operations. One approach for pharmaceuticals is to put tags on pressure-sensitive labels that go on primary containers.

Pressure-sensitive labeling technology is proven, but the reliability of RFID chips on the labels plays a big role in high-speed operations. Pharmaceutical packaging requires verification of the information on chips, much the same as regulations require verification of other codes.

However, the current chips are yielding only 60% to 70% verification rates, an unacceptable figure on pharmaceutical packaging lines where 100% verification is the mandated level. That degree of failure rates concerns consultant John Bitner. “Each of the tags is going to have to be applied on the packaging line and then verified at line speeds. I don’t think it is going to happen,” he says.

On the other hand, notes National Label’s Sellars, under FDA’s timetable, 2004 is a development year, and that is what is occurring. “We don’t have the technology today, but it will come. Do I think it will happen by 2007? Sure.”

Howard Leary, vice president applied engineering at Luciano Packaging Technologies, thinks applying tags is within the scope of current line engineering technology. “There are no signs on the horizon that it shouldn’t work. There may be some issues of slowing a line down to program the chips on high-speed lines,” he says.

Don’t forget bar codes

While RFID gets all the “press,” bar-coding will still play a role in packaging security. In its February report on counterfeiting, FDA says that, although RFID is the preferred technology, “Two-dimensional bar codes may be used for some products.”

Peggy Staver, director of trade operations, product support for Pfizer, says, “It could be a combination of bar codes and RFID. What I’m hearing in meetings is the idea that bar codes and RFID will coexist for some period of time. Near-term we want to take actions to further secure the supply chain. Bar codes at the unit level may provide an opportunity to enable an electronic track- and-trace system near-term, while RFID technology continues to evolve for unit-level pharmaceutical applications in the future.”

So, who is using bar coding as an anti-counterfeiting technology and how are they using it? Pharma-ceutical companies see that information as confidential. “People will talk with you in terms of what can be done, but nobody wants to tell you what they are doing because that would assist the counterfeiter,” states one packaging manager for a major pharmaceutical company.

In terms of what can be done, 2D bar codes—printed “invisibly” with techniques such as UV inks or lasers—may hold some promise. They’re now being tested by consumer packaged goods companies.

Among such systems is one from Portola Packaging. At its core is the ability to generate up to 8ꯠ million, billion, billion encrypted codes and print each code in an area as small as 1 sq cm. The system downloads codes via a secure Internet connection, and it can print at speeds to 300 packages/min. It then downloads the data to a database that allows authentication of individual packages.

Individual packages can then be instantly authenticated in the field by scanning codes and uploading them wirelessly to a secure server for decryption.

“It’s a matter of having someone at the end of the supply chain with a scanner,” explains Jack Watts, president of Portola Packaging. “If the person with the scanner can access the database wirelessly on the Internet, then they can verify that the code on the package was generated on a particular packaging line and is valid. The codes are nonserial, nonrepeating, and appear random—and the system can detect duplicates.”

The system accommodates both laser and ink-jet imprinters. And it can produce human-readable alphanumeric labels that can be verified via cell phone. The system, according to Portola, is under test by a major consumer packaged goods company in China.

New to packaging

The final part of the puzzle, according to FDA’s report, is the use of authentication technologies “such as color-shifting inks, holograms, fingerprints, taggants, or chemical markers embedded in a drug or its label.”

Some of these technologies, such as color-shifting inks, will come from outside the packaging industry. For this technology, think in terms of some of the newest U.S. $20 bills. When the bills are turned, the inks reflect different colors as they are viewed from different angles. Many of the anticounterfeiting technologies that can be applied to packaging start with currency, notes Jon Senft, vice president, Consulting for Reconnaissance International.

Another anticounterfeiting tactic is the hologram. This established technology was once considered a strong anticounterfeiting measure because holographic patterns were hard to copy. Today, however, holograms are easier to copy, so having one on a package is not as strong an endorsement that the product is genuine as it once was. However, from the consumer’s perspective, explains Senft, the hologram offers reassurance that the manufacturer is doing something to protect the product’s integrity.

Taggants and chemical markers are other tactics. These can be introduced in the inks used to print packages or they can be in a substrate component, such as the adhesive holding layers together in a multilayer structure. Specific chemicals are added to the formulation at small, well-defined levels. For example, explains Mike Impastato of Flint Ink, an ink may add a specific level of one compound and a specific level of a second compound in it. The levels are specific for the manufacturer or even for a specific product that the manufacturer makes.

According to Stephen Postle of Sun Chemical Corp., using inks as a carrier for taggants as opposed to putting taggants in a substrate brings a key advantage: They can be changed more readily than substrates. “You’re better able to target what you are doing,” adds Postle. Without citing specific examples because of security concerns, he explains that it is possible to have different ink-based solutions even for different varieties in a product line.

Inks also may be a more cost-effective carrier for taggants than substrates, adds Postle, because less taggant chemical is needed in an ink than in a substrate, where the chemical must be dispersed throughout.

To work as an anticounterfeiting tactic, taggants require that the packager using the method have people out in the field who can inspect packaged product. In most cases, the verification requires some form of light or energy source directed at the package. Depending on the taggant used, a particular kind of pattern or “fingerprint” comes from the package. If the fingerprint doesn’t match that which the packager put into the package, then the container is a counterfeit.

X-ray fluorescence is an example of one way to “read” a package. The X-ray causes all the materials within the package to respond with a fluorescence—they reflect back energy. Because of a particular substance used as a taggant, the package emits energy in a specific way that can be read on a handheld device.

Whatever the technology chosen to combat counterfeiting, the threat is real and it is global. The strategy of using multiple security techniques to fight counterfeiting is echoed by regulators, packagers, and suppliers. The biggest challenge is to choose the right methods that will have the best effect in foiling the efforts of counterfeiters.

See sidebar to this article: Authentication through DNA codes

For a white paper on Traceable Packaging Solutions, see: packworld.com/go/w124