Detergent pods are concentrated gels in small packs. They hold premeasured quantities that are simply tossed into a wash load, without further fuss or mess. The appeal of the pods can be summed up in one word—convenience—and on that front, the product delivers. Unfortunately, the pods have been mistaken for candy by thousands of children who have ingested the contents and suffered various levels of gastronomic and respiratory distress. Marketers of the pods did not intend for any child to be harmed; nonetheless, there is a basis for asking whether those marketers should have foreseen that young children might mistake the product for candy.

Children are predictable

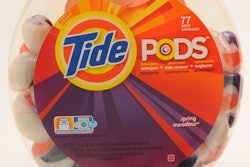

The susceptibility of children to product-related accidents is the result of mobility, dexterity, and curiosity, making pre-toddlers (beginning with the crawlers) to kindergarteners (and even older) the range that is particularly worrisome. At the lower end of that range children experience much of their worlds by placing anything graspable into their mouths. Even after children have grown out of that stage, their associative skills make them vulnerable. Not being able to discern meaningful differences among some items, children associate along such simple parameters as size, shape, and color. Small, colorful shapes can exert an irresistible appeal to children. That’s a truth embraced by a variety of manufacturers of products for children: for example, crib mobiles (the components), rattles, teething rings, and (of course) candy. For manufacturers of products that are not intended to be handled—let along ingested— by children, it makes sense not to bestow those products with the aforementioned characteristics.

So, why were the detergent pods designed as they were? Granted, their size and shape are consistent with the concept of convenience. But did they have to be designed with such irresistible, swirling colors? It doesn’t appear that the colors are functional in any way, and since it’s the colors that lure children to the pods, why the colors at all? Maybe it’s a marketing ploy; after all, colors are known to evoke emotions and perhaps their use is an attempt to inject levity into an otherwise humdrum chore. So with detergent pods, consumers have a product that’s convenient and visually attractive; however, that latter characteristic might not have been given its due consideration regarding its influence on children.

There was a history

Prior to their recent launch in the United States, detergent pods had been sold for years throughout Europe. They sported similar sizes, shapes, and colors as those of the U.S. versions. The European detergent pods also were mistaken for candy numerously by children. U.S. firms seem to have been either unaware of what happened in Europe or didn’t think it was worth factoring into latter-day packaging. As improbable as either scenario seems, there’s no denying that U.S. firms not only followed suit with the primary packaging (the pods, themselves), but furthermore, packaged them in clear, lidded containers, resulting in a striking resemblance to a bowl of individually-wrapped candies.

In the U.S., news coverage of accidental ingestions of detergent pods was high in May 2012; however, the coverage has begun anew, here in September. That the story has been given new legs might be a combination of the increasing number of incidents (reported at the time of this writing to be several thousand) and a perception that manufacturers are not responding quickly enough and effectively enough.

Did research fall short?

The U.S. launch of detergent pods wasn’t a hasty one; for, according to published accounts, the category leader spent years in its buildup. One would assume that during that time reams of research were conducted. One would additionally assume that more than an incidental portion of that research was conducted on the packaging. However true those two assumptions might be, somehow, what wasn’t adequately researched was child safety.

Maybe the packaging design research focused primarily on function and aesthetics, covering questions such as these: does the primary packaging dissolve quickly; does the lid open and close easily; does the container allow easy access to its contents; do the packaging components combine for good shelf-impact?

What also was needed was research on whether the packaging/product posed a hazard to children. And if (or since) the answer is yes, the response should go beyond a warning, such as, “Keep away from children.” Warnings are a third-tier defense. The first-tier defense is to design out the hazard, i.e. not make the packaged product confusable with candy. The second-tier defense is to impose a physical safeguard, i.e. a child-resistant feature (the category leader has announced that it’s switching to a lid with a double latch.

Package design research traditionally has been divided into quantitative and qualitative methodologies, surveys and focus-groups being respective examples; however, children are not respondents and if they are to be factored into the research specific questions must be asked about children. Another perspective can be gained through ethnographic research, an observational methodology whereby the researcher observes clients using the product in the home (or whatever the use environment). Hypothetically, an attuned ethnographer might observe that some mothers, by necessity, do laundry and watch children at the same time, the children being in the laundry area. That same ethnographer just might pick up on any interest in the packaged product shown by the children and be able to make reasonable inferences regarding what it portends from a safety standpoint.

And now, the answer

By my analysis, the ingestions were foreseeable. It’s a subjective opinion; however, what’s far less so is that few things rile the public more than a belief that children have been needlessly placed at risk. Now, there’s a chorus of pediatricians and poison-control center spokespersons advising parents of young children to not buy detergent pods. Translated, those parents are being told to toss the pods off the shopping list; and, that’s not the kind of “podcast” manufacturers want.

Sterling Anthony is a consultant, specializing in the strategic use of marketing, logistics, and packaging. His contact information is: 100 Renaissance Center- Box 43176; Detroit, MI 48243; 313-531-1875 office; 313-531-1972 fax; [email protected]; www.pkgconsultant.com