Every package redesign is a gamble, but the odds for a favorable outcome are enhanced by following best practices. Unlike lists of misguided reasons and good reasons for package redesigns, sequence matters with this list of best practices because they are step-wise.

Have the support of top management. That’s not to suggest that top management should be directly involved in package redesign. Support should take the form of making it clear throughout the company that packaging is a strategic tool and a source of competitive advantage. As a logical consequence, package redesign receives the same recognition. Of the various ways to demonstrate support, none are more convincing than giving packaging a position on the organization chart reflective of its prowess.

Have a realistic packaging philosophy. At the core of this best practice is understanding what packaging can and can’t do. Without that distinction, package redesign can be undertaken for the wrong reasons and with the wrong expectations. Packaging’s capabilities are limited to these functions: containment, protection, communication, convenience, and utility. The functions don’t only apply to consumers, but to partners throughout the supply chain. A package redesign is misguided if it will not improve one or more of those functions.

Take an interdisciplinary approach. Marketing is not the only discipline with a vested interest in package design. Others include sales, line operations, distribution, legal, and purchasing—just to name a few. The various interests can conflict, requiring compromises and trade-offs for an optimal net result. No discipline should have carte blanche authority. An advisable alternative is a committee, its members representing the various vested interests, and headed by someone with a packaging-related title.

Have effective channels of communication and information. Indicators that might warrant a package redesign can be numerous and dispersed. Effectively funneling them requires monitoring relevant environments, tapping relevant informational sources, and conveying what’s learned to the right parties. The objective is to convert information into intelligence and to make that intelligence actionable. The network should not be more complex than needed; however, in all cases, what’s needed is more than just a 1-800 consumer feedback line.

Make data-driven decisions. All the preceding practices will facilitate making the fundamental decisions: whether a redesign is warranted, and if yes, the form it should take (graphic, structural, or both). It’s easier to achieve consensus when vested parties believe that decisions are supported by the numbers. While it’s fair to argue against an unquestioning reliance on analytics, even more detrimental would be such reliance on going with one’s gut (a common cause of corporate indigestion.)

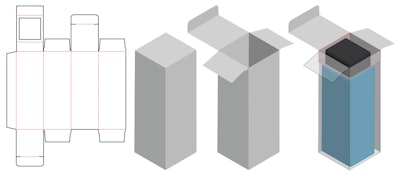

Compose a redesign brief that’s comprehensive but concise. Every package redesign project has to its advantage a history, compiled by the present design. The redesign brief must retain the features valued by the target consumers, while incorporating revisions for overall improvement. The approach favors incremental changes. On the other hand, a major overhaul would suggest that there was something fundamentally deficient about the process that produced the present design. A redesign brief should be of exacting detail, regardless of whether the redesign alternatives are generated by an outside agency or in-house.

Conduct streamlined evaluations. When the redesign is not done in-house, invite several design agencies to present their credentials. Vet them down to one. Have that agency come up with several redesign alternatives. There’s no need to get inundated with alternatives, thinking that among them will be the perfect redesign. Perfection is as mythical as are unicorns—except one would certainly recognize a unicorn, if ever encountered.

Conduct streamlined testing. Rather than pursuing perfection, the pursuit should be for a redesign that does not embody a major error. Examples of such an error might be consumer confusion about product category, or colors that have negative connotations relative to the product category. Qualitative and quantitative tests are numerous, and a company should not get bogged down with an unwieldy battery of them. Limit testing to a few methodologies, chosen for what they purport to measure.

Document in detail. The need for a package redesign should not come down the pike often, at least not for the same product. That, in itself, is reason to document each instance. What’s to be avoided is reliance on the recall of past participants (who may have moved on, anyway.) Another benefit accrues to companies with multiple brands or different products under the same brand. There’s no need to start from zero, procedurally, with every redesign project. Lastly, detailed documentation provides a basis for grading how well a project was managed, and therefore, a basis for improving the process.

Sterling Anthony, CPP, consults in packaging, marketing, logistics, and human-factors. A former faculty member at the Michigan State University School of Packaging, his contact info is:100 Renaissance Center, Box-176, Detroit, MI 48243; 313/531-1875; [email protected].