About a dozen visually impaired patients in the Chicagoland area are the first to test a new “talking label” system that reads aloud, in English, prescription information and instructions from a label affixed to a medicine bottle.

Called “ScripTalk,” the system uses radio-frequency identification (RFID) to enable patients to use a small device no larger than a hand-held computer to read information embedded in the “smart label” on the bottle. With the push of a button on the scanner that’s equipped with a speaker, label information is synthesized into audible language that provides information such as patient name, drug name, dosage instructions, prescription date, number of refills remaining, drug interaction warnings, pharmacy phone number, etc.

The patients are part of an ongoing pilot study initiated late this past summer at Hines Veterans Hospital. Located in Hines, IL, just west of Chicago, Hines is one of approximately 145 hospitals under the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. While there’s no definitive timetable for the study, these patients will determine the trial’s success, along with the pharmacy professionals who manually apply ScripTalk labels to prescription bottles in a hands-on operation at the outpatient pharmacy at Hines.

ScripTalk was developed by En-Vision America (Normal, IL) in partnership with Inside Technologies (Aix-en-Provence, France). En-Vision supplies the reader device that was designed by Phase IV Engineering (Boulder, CO). Inside Technologies provides the RFID microchips, each of which contains 2 kb of memory. En-Vision outsources the application of a chip to each label.

Labels are made of two structures that are laminated together. The main structure includes a 2-mil white polyester Z-Ultimate™ facestock with a thermal-transfer printable top coating from Zebra Technologies (Vernon Hills, IL). Zebra also makes the printer/encoder that prints onto the facestock, using what the supplier refers to as its 5100 premium resin ribbon.

Beneath the facestock is a 0.8-mil acrylic adhesive. The adhesive covers a 2.6-mil plastic “carrier” material, into which a copper antenna is etched. The RFID chip is machine “mounted” to the antenna by an outside firm. A 1-mil layer of acrylic adhesive covers those materials. It is covered by the second part of the structure, a 3.2-mil semi-bleached kraft release liner. Total thickness is 9.6 mils (±10% excluding the RFID chip).

Appropriate for the study

According to Robert Silverman, clinical pharmacy information specialist at Hines, En-Vision America’s plan is to try to incorporate the use of ScripTalk at other VA sites. “They contacted our Pharmacy Service, and our Investigational Review Board approved the study,” he says. “As far as I know, the VA is getting the first attempt at ScripTalk, and Hines is the first of the VA hospitals to use it.”

Hines, Silverman says, “is one of the few VA hospitals that has a Blind Rehabilitation Center (BRC), which specializes in training veterans to cope with their blindness.” He indicates that most patients have some vision. “Hines is an appropriate pilot site because we have an ‘audience’ for it,” he continues. “The center determines which patients should be part of the study. Each patient then consents to be part of the study.”

The study involves patients who are nearing completion or have completed the center’s training program. The rehabilitation program lasts about 45 days, though the time varies depending on the patient’s limitations. During training, patients reside at the center’s own building, which is located close to the outpatient pharmacy involved in the ScripTalk program on Hines’ sprawling campus. Upon completion of the rehab program, patients return to private living, where they keep a scanner to use with their prescriptions.

Pharmacy’s role

“Shortly before patients are discharged, they get their prescriptions,” explains Silverman. Prescription information for each veteran is entered into the hospital’s electronic patient records system. Both VA pharmacists and doctors can access the system. Doctors can enter prescriptions through the system, rather than writing them on paper.

Silverman wrote some of the software used to help send information from Hines’ computer system to the Zebra printer for encoding the ScripTalk labels. Besides Silverman, several other Hines employees are critical to the ScripTalk project. They include David Zacher, chief of Pharmacy Service; Dan Smith, automated data processing coordinator for the BRC; and Jerry Schutter, chief of the BRC.

The pharmacy receives the order and processes it, much like it would for any order. Each bottle receives a pressure-sensitive label, whether or not it’s a ScripTalk order. That primary label is printed by one of three laser printers in the pharmacy, then hand-applied.

“The only difference for patients enrolled in this study,” Silverman points out, “is that the records indicate that the prescription requires a ScripTalk label.” The word ScripTalk appears on the primary label. It reminds the pharmacist or technician to retrieve the actual ScripTalk label.

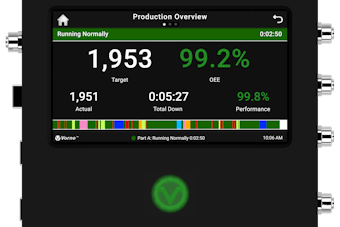

The ScripTalk label is printed on the Zebra thermal-transfer printer/encoder, a “test” machine devised for this application. The unit is equipped with its own antenna, which is embedded beneath the machine’s printhead. The antenna in the printer communicates with the antenna in the label.

The motor-driven printer/ encoder uses information from the software program and encodes the data onto the RFID chip in the label. The machine also verifies that the data is correct. Then the machine prints the appropriate information onto the 2-mil white polyester facestock and ejects the label.

The ScripTalk label is peeled off the carrier and hand-applied directly on top of the primary label on the traditional brown apothecary bottle. Hines realizes that creating and applying the label is an extra step, but they believe it’s a system that works well. Finally, the drug is filled into the bottle and a closure is applied.

Since it first began printing ScripTalk labels in late August, Hines has changed the size of the label. At the time of Packaging World’s November visit, the pharmacy was switching from a 1”Wx½”H label to one measuring 4”Wx1 ¾”H.

“One of the reasons for going to a larger label,” says Zacher, “is that the larger label, along with the ScripTalk notification that appears on the computer record and on the primary label, helps pharmacy personnel identify the prescriptions for the pilot study.

“The second reason for the larger label,” Zacher continues, “is that with the small label, the patient had to almost touch the label with the reader for it to read. With the larger label, the reader can come within several inches of the label and it will still scan properly.”

Evaluating

Hines officials made it clear that as federal employees, they could not recommend ScripTalk. “The success of the pilot study depends on two things,” says Zacher.

“First is patient satisfaction. That will take time to evaluate,” he adds, “because there are few patients at this point, and they haven’t been using the system long enough to make any judgment.” Second, Zacher says, “is pharmacist satisfaction. It cannot be something that adds to their workload. From what we’ve seen, it will have minimal impact.”

While Hines cannot openly recommend ScripTalk, its future looks promising. “I anticipate that once these patients respond [to surveys] with satisfaction, we would begin talking about changing this from a study to an actual ‘product,’” Silverman notes. “I would have to bundle up the software I’ve written and make it available to other VA hospitals. That’s the goal.”

He says that ScripTalk could benefit not only the visually impaired, but also those who are functionally illiterate. In conclusion, he believes “it’s a good service to our blind patients, and that’s why we were interested in it initially.”