The transition from mechanically linked cams and shafts to servo-based packaging machinery that has unfolded over the past 20 years or so has brought countless benefits to machine builders and, more important at the end of the day, machine buyers. More than anything else, this shift has brought a level of versatility and flexibility that could never have been achieved back in the days of mechanical linkages.

But the demands that drove this transition—SKU proliferation, multiplying number of retail channels, customization of packaging based on specific demographic characteristics—have continued to intensify, to the point where some packaging machinery builders find themselves in need of a next big thing if they hope to keep pace. At WestRock Co., the next big thing is using model-based systems engineering to decrease time to market in designing and building its packaging machines. The two key solution providers pitching in were Dassault Systèmes and Bosch Rexroth.

WestRock is the Norcross, GA-based firm that emerged from the July 2015 combination of MeadWestvaco and Rock-Tenn. It’s one of the world’s largest paper and packaging companies, having $14 billion in annual revenue and some 39,000 employees in 30 countries. It’s also the only North American company in the paper packaging industry with an in-house machinery manufacturing and service division that designs and manufactures a complete line of secondary packaging equipment, primarily multipacking and case packing equipment. More than 80 standard and customized configurations are offered, some highly automated and others semi-automatic.

“We were as advanced as anyone in the business when it came to capitalizing on what servo drives and motors let you do,” says John Perkins, VP Global Systems at WestRock. “But as package format varieties continued to increase in number, our machine designers reached a point where it became ever more difficult to envision and account for all the formats involved. What we needed was a way of making it okay for our machine designers to make a mistake virtually rather than physically. This led us to start working with Bosch Rexroth and Dassault Systèmes towards the goal of simulating machines running all these various configurations so that we could see where problems would be on a CAD station rather than build the machine and have it crash physically on our plant floor. In addition to wanting to predict the mechanical interferences that might occur we also wanted to go a step deeper and ask how do you size what drives the machine? How do you make sure the servo motors, the drives, the gear boxes, and all the other parts that are being actuated can work within this envelope and run reliably and not fail?”

Model-based systems engineering

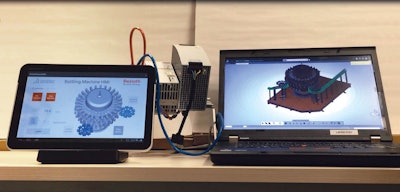

What the firm needed was model-based systems engineering—where packaging machinery, among other things, can be designed and built virtually rather than physically thanks to open and nonproprietary simulation software that makes it easy for multiple stakeholders to collaborate in modelling projects. Fortunately for them, Bosch Rexroth and Dassault Systèmes were already in conversations about how this kind of virtual machine design might be accomplished. At the center of their work was a programming language called Modelica, an object-oriented modeling language for component-oriented modeling of complex systems containing mechanical, electrical, electronic, thermal, control, or process-oriented subcomponents. Dassault Systèmes’ Issam Belhaj, World Wide Technical Manager for Industrial Equipment, describes how WestRock, Dassault Systèmes, and Bosch Rexroth became the legs of a three-legged machine-building stool.

“As of 2015 WestRock was a buyer of Bosch Rexroth controls components—servo drives, servo motors, controllers, and so on. Also by that time, quite independently Bosch Rexroth and Dassault Systèmes, a leading supplier of modeling software and CAD solutions, had been exploring how virtual machine design might be done through Modelica simulation programming language. Bosch Rexroth had already developed their own libraries for their range of products, and they were able to connect their controllers to Modelica through an IP address. This dovetailed nicely with our approach, which depends on being able to connect hardware to our software. When we and Bosch Rexroth demonstrated some of our early joint efforts at a Modelica conference, that’s when WestRock picked up on it. So by the end of 2015, the three of us were locked in on a goal of virtual machine design and commissioning.

“Bosch Rexroth was, and probably still is, ahead of the pack when it comes to Modelica, so that made them a good partner for us. They have been able to provide the actual predictive curves of their motors and drives. So when we plug that into a simulation, we’re not just looking at a theoretical. If I need X amount of torque I can actually take the Rexroth motor that’s been selected and the Rexroth drive running that motor and I can put the specific profiles of how those devices work in practical application and put those profiles into the simulation.”

Bosch Rexroth’s Open Core Engineering approach also makes them a good strategic partner for Dassault Systèmes, adds Belhaj. (For more on Open Core Engineering, see pwgo.to/2638) With the Open Core Interface, Rexroth provides a software interface that permits enhanced access to the control core, offers numerous programming languages, and allows the integration of smart devices into automation systems. Open Core Engineering brings together the previously separate worlds of the PLC and IT automation as a broad portfolio of software tools, function toolkits, open standards, and Open Core Interface. It addresses the complete development cycle of a machine, from design to implementation to production.