The coming out party for a new breed of linear servo motors appears to have been Pack Expo International 2012. At that show, American machine builders R.A. Jones & Co. and KHS Bartelt each exhibited a machine using the Jacobs Automation Intelligent iTRAK® system with Rockwell Automation controls. In addition, Beckhoff introduced its XTS eXtended Transport System, a similar motor, expected to produce application examples in Europe within the next 12 months.

The R.A. Jones application called IndeCart® 2 was the transfer device between an incoming product stream and a Legacy continuous motion end load cartoner. The device accepts incoming product with random spacing and syncs it into the machine within a very small footprint. This machine is considered a test platform by Jones and has not been sold. The KHS application was integrated into its Innopouch K400 simplex/duplex horizontal form-fill-seal machine, creating a pitchless machine that allows each pouch to be independently controlled throughout its journey within the machine. With some modifications since the show, this machine is on its way to a customer.

The key to both of these packaging applications is the ability to place multiple movers or carriages (12 for Jones, 60 for KHS) onto a single curvilinear track and to independently control the motion profile for each carriage as if it were a completely independent servo axis. This allows designers to ‘break the math’ for systems that have heretofore been constrained to operate in a synchronous mode, constrained by the pitch of a chain or the speed of a line shaft. Each portion of a machine may operate asynchronously with respect to the others, using the independently controlled mover to match up timing as required. In essence, the machine can be coordinated to the uniqueness of each individual product rather than the product needing to be uniformly presented and slaved to the machine. It’s individualized customer service for each product handled by the machine.

“Transformational” and “game-changing” are the terms most often used by those who describe this technology, even though it actually isn’t that new. I first signed a non-disclosure agreement on this motor and its packaging applications about 10 years ago. But as with the application of rotary servos to packaging machines as foreseen in the 1980s and realized in the 1990s, this application needed time for refinement and time for the compounding effect of Moore’s law—the widely held belief that computing power doubles about every two years—to bring sufficient, affordable computing and network power to bear on the need for controlling the motor. Both Jacobs and Beckhoff cited cost-effective high speed networking and software throughput as the key enabler of these new motors.

Learning from past developments

One way to speculate about how multi-axis linear technology might evolve is to look back at how coordinated multi-axis rotary servos made their way into widespread use. I see many parallels already, including the companies involved as early adopters. In the rotary case, there were parallel developments going on across the Atlantic, with U.S. entrepreneurial involvement in the earliest U.S. and European applications. Applications moved forward in stages, identifiable to the point that the industry gave the stages names: Gen1, Gen2, and Gen3. These stages were documented and defined by the OMAC Packaging Workgroup and were often referred to by end users and suppliers.

Today the Jones IndeCart® 1 is a good example of a Gen1 solution relative to these linear motor systems. This system uses a series of carriages that traverse an oval-shaped linear track system. Propulsion for these carriages is provided by four chains that share common sprocket centerlines. Each chain has two carriages attached to it, 180 degrees apart, and is driven by its own rotary servo motor and gearbox. A carriage, from each chain in turn, is timed to meet an incoming product or products, and then it is advanced to present the product at the proper time to the next stage of the machine. This system uses the generally available and accepted technology of the day to achieve the needed outcomes with fairly complex engineering, design, and execution.

As a Gen2 solution, IndeCart® 2 uses the emerging technology of the iTRAK® to replace the chains and rotary servo drives with a more elegant linear motor solution that offers a simpler appearance requiring fewer moving parts. The machine as displayed at Pack Expo maintained two rotary servos to transport the carriages around the curved portion of the track, but both Jones and Jacobs Automation seem to agree that an updated design would use linear motors for all 360 degrees of movement, reducing the complexity even further. Unlike the KHS machine that has its carriages traversing a horizontal plane, the carriages on the Jones machine traverse a vertical plane, requiring that some thought be given to the effects of gravity and the handling of the carriages in the event of a power failure.

Gen2 rotary servo solutions were often considered technical successes and business failures, meaning that the added cost of the new technology was not justifiable. This seems consistent with R.A. Jones’ current experience with linear technology. The use of the iTRAK® system, especially when the curves are added, creates a simpler, easier to build, presumably easier to maintain and more flexible solution, but at a cost that Jones feels is currently too high. Second generation systems may not produce all of the cost benefits available from transformational technology because they tend to do the same things in new ways. But they are a necessary step along the path to third generation systems that may actually do new things in new ways. Third generation benefits may substantially exceed anything that was originally envisioned when a second generation solution was developed.

As with rotary servos, not all potential applications will be cost effective early on, and sometimes builders and users develop a bias against a technology because of its cost. I urge caution in judging technology based upon its early applications. It was frequently heard throughout the 1990s that mechatronic servo packaging machines were not desired by customers, were too expensive to build, were too complex to support, and were just bells and whistles for the sake of bells and whistles. I think that the price/performance picture has been clarified since then and that those arguments are now all behind us. Where would our industry be today without mechatronics and rotary servo technology?

Today linear motors are reported to be under a similar cloud. In the press releases from Jacobs and partner Rockwell Automation, the term “linear motor” is not even used. Instead, the system that is built on top of Rockwell’s Anorad linear motors is described in terms like “magnetic wave technology.” Reminds me of when Allen Bradley tried to disguise a DEC MicroVAX by naming it the “Pyramid Integrator.”

A linear motor is not an appropriate solution for replacing every pneumatic cylinder on a machine. Linear actuator supplier Linmot has an application example that compares embossing an egg with an air cylinder to embossing an egg with a linear motor actuator. To the untrained eye, the two solutions may appear to do the same thing. But the ability to reliably control the speed, acceleration, and resulting force of a linear actuator would certainly make it the more appropriate solution for embossing an egg, but probably not for pushing a carton off of a conveyor. (For more on appropriate use of technology, see www.bit.ly/pwe00470.)

Total cost of ownership should be looked at in every financial evaluation, but especially when new technology is involved. Rotary servo machines provided opportunities to reduce the footprint of a production line over their non-servo alternatives. This allowed modernization to take place in locations where it might not otherwise have been possible. In green field sites these reduced footprints provided considerable savings in building construction and ongoing utility costs and freed up funds for more expensive packaging equipment. KHS points out that the iTRAK® system permits them to shrink their machine’s length by 14 to 26 feet and reduces design and assembly time for them by two weeks. The end user also benefits from ongoing reduced maintenance costs and much faster changeovers.

All of these changes must be factored into the overall cost/benefit equation creating a win-win-win situation. Technology providers win with higher profits from new technologies compared to supplying commodity parts. Machine builders win by being able to create higher value machines that may command a premium from the user. And packagers win with machines that improve their operational performance and quality.

Understanding the Technology

As mentioned previously, advances in computing and network power have been the primary enablers of this new class of motors. Despite all of the underlying processing and communication that is taking place, the application engineering necessary for implementation seems to be rather straightforward. Keith Jacobs, founder and CEO of Jacobs Automation, says that they can teach a competent rotary servo motion programmer all he or she needs to know about iTRAK® in about two hours. Engineers at KHS and Jones support the assertion that the motor system is easy to program. Let’s now peel open these new motors a bit to understand how they work and why they are at the same time so complex yet simple to use.

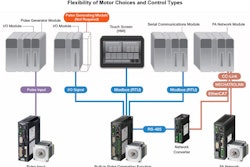

The Beckhoff and Jacobs motors share some similarities, yet they’re different. No one from either organization would discuss any underlying patent issues; only time will tell if there are any. Both systems are assembled from pre-configured straight and curved track sections, not unlike assembling a model railroad. At present, the sizes and shapes of track sections are limited, but both companies report that more options are under development.

A track section consists of power connections, network connections, a series of motor windings or coils, servo drive electronics, and linear encoder electronics. A linear bearing rail system is either part of the track or is installed adjoining it. The carriages contain rollers that engage with the rail system along which they move. The rail system maintains the air gap between motor windings and the rare earth magnets that are attached to the movers. In the Beckhoff case there are two rows of coils and two rows of magnets, which act together to cancel forces perpendicular to the direction of movement. In the Jacobs case, there is one row of each.

The track sections have a number of coils embedded within them. The number and spacing of these coils and the length of the carriages determine how many of these moving components can coexist and be independently controlled on one track segment.

Each coil within the track must have power commutated to it just as would occur for a rotary servo winding; however, a typical rotary servo has only 3 phases that are powered by 3 servo amplifier output stages. Historically these drive modules have been separate from rotary servos, but in recent years, rotary servos have been built with drives integrated within the motors. The linear track modules use integrated drives. If we suppose that a track section has embedded within it 12 coils or pairs of coils, then that section could be thought of as also containing four 3-phase servo drives or one 12-phase drive. Therefore, if we assemble a linear servo motor track into a loop made up of eight track sections, there would be embedded within the loop the equivalent of 32 3-phase or eight 12-phase servo drives. The network connections to and within the track sections serve to allow these drives to communicate with each other and with a master external motion controller.

As with a rotary servo system, the ability to accurately control a motion profile requires closed loop control using some sort of encoder. Each track section, therefore, includes a linear encoder that must appear as an extension of the encoders in each of the other track sections. The carriages contain a flag or target that can be read by the encoder system. The ability to locate a carriage on these tracks is quite high with repeatability in the range of 10 micrometers and accuracy a bit less.

We can now see that we are assembling some amount of complexity within this curvilinear motor. We have a stator with 96 phases controlled by eight embedded 12-phase servo drives and, on the other side of the air gap, we have a mover containing rare earth magnets, the position and velocity of which are fed back to the drives via an embedded series of encoders. “But wait! There’s more!”, as the man on the late night television commercial would say.

There is not just one moving carriage on this track. KHS has 60 on their machine. The smaller track in our example might accommodate a dozen carriages, each behaving with a different motion profile at any instant of time. As these carriages travel over the various track sections, they can change direction; accelerate or decelerate; follow each other according to a cam, gear or other profile; follow and sync to an external signal; apply compressive or extensive forces; and perform a variety of tricks as though each is a single-axis robot. Control of the carriages is being constantly passed from one drive to another and from one track section to another while the encoder is keeping track of the identity, absolute position, and velocity of each one at all times. The computing and communication requirements for all of these combinations increases exponentially as multiple moving carriages are shared across multiple drives. This is why computing power and network speed has been the gating factor for development of these motors—at a price point suitable for packaging. (For a discussion of the impact of Moore’s Law on packaging machinery, see www.bit.ly/pwe00471.)

The complexity is handled by software written by the motor manufacturer. I did not seek, nor can I imagine being offered, details on how this is accomplished. One can only imagine a program handling large arrays of numbers or matrices that keep track of which carriage is over which winding in which track section at any given instant of time and how the signals to every winding must be altered to put each carriage into its next incremental state. The good news for the application programmer is that he or she need only think of each moving carriage as an independent axis and program its motion as though it were a standard motor with its own dedicated shaft, windings, and encoder. In the Jacobs case, programmers use standard Kinetics software in a ControlLogix processor, and in the Beckhoff case, programmers use TwinCAT software in a Beckhoff PC. Jacobs provides an industrial PC with their software that sits on EtherNetI/P between the Rockwell programmable automation controller and the motor. Beckhoff provides a software module that runs on the same processor as the TwinCAT software which is connected to the motor via EtherCat.

The future

As we move forward over the next three years, expect to see more applications of these linear servo motors appear in cartoners, pouchers, baggers, bar infeeds, and probably places that we haven’t thought of yet. With companies like Rockwell and Beckhoff behind these products, entrepreneurs like Keith Jacobs driving development, and early adopters like R.A. Jones and Bartelt developing applications, it would appear that critical mass is developing. Bartelt’s Roger Calabrese says that this technology will forever change the way that pouching is done. And R.A. Jones’ Jeff Williams says that the technology will be advantageous, will be evolutionary, and can be revolutionary. Let’s check back in a couple of years and see if these predictions come true.