For more than 30 years, Mill-Chem Manufacturing, Inc., Thomasville, NC, has served as contract manufacturer and contract packager for private label household chemical products. As a SIOP (Sales Inventory & Operations Planning) business, the company’s portfolio is varied, producing cleaning supplies for janitorial/industrial markets, branded personal care and home use cleaners for the consumer side, and even some nutraceuticals or specialty enzymes destined for food producers.

But even with such wide a variety of products, there exists a common thread. As the company grew, it began to differentiate itself by gravitating to “green” cleaning formulas, with “green” meaning organic in this case.

“We were one of the first companies in our segment to try to go green,” says Elliott Miller, Asst. Production Manager, Mill-Chem. “We had our struggles at first, but now, of our 350 different products, roughly 30 percent of them are organic.”

Floor care products, household cleaners, and laundry detergent are among Mill-Chem’s largest volume categories, as are fully organic cleaning products that are shipped to retail destinations like Walmart, Whole Foods, Lowe’s, Kroger, Meijer, and Ace Hardware. Increasingly, Grainger and Amazon fulfillment centers are the products’ destination.

Coding and marking a priority

Given the plurality of SKUs moving through Mill-Chem at any given time, the complex chemical nature of the products, and as a requirement to maintain its organic and GMP certifications, traceability to batch and lot is important to the company. It's also important to its customers, and to the retailers that sell the cleaners and detergents. This puts a lot of pressure on the coding and marking systems—not only to accurately mark product, but to handle a variety of geometries and sizes and keep the line up and running without smearing or clogging that would create downtime.

“I'm always trying to find a way to be more efficient because the less money it takes me to put a bottle together and to package that bottle, the more money I make on the backend,” Miller says. “Coding and marking is an important variable in that equation.”

He says has used well over a dozen different types of coding and marking systems in his more than 27 years with Mill-Chem, with continuous inkjet being the most recent standard. But Miller perceived problems with some continuous machines in that each print head required maintenance and constant observation to be sure it was working. It became labor intensive to be constantly cleaning the heads to keep them functioning as they were supposed to. And if the heads aren’t constantly maintained, that can lead to line stoppage, he says.

“A line that’s down in my production facility comes out to roughly $725 per hour that I lose in labor, overhead and lost earnings,” Miller says. “That's not including product loss for errant marks, smudges, and things that require rework. And we tend to run at about 1,600 to 1,700 bottles per hour, so that’s the amount of product we aren’t moving through for every hour we’re down. That’s a lot of opportunity cost.”

He also noticed that continuous inkjet coders require two inputs—ink and attendant solvent—so there’s more to order and more to inventory than the alternative, cartridge-style coders that require a single input. He began experimenting with cartridge-based thermal inkjet, an impulse capillary vaporization technology that essentially superheats liquid ink to a vapor in the form of a bubble, then without the need for any pressure, applies superfine ink particles in such a way that allows for extremely high resolution and small character size.

Now, a tradeoff with this technology is the throw distance. Thermal inkjet requires close proximity to the substrate, less than 4 mm compared to continuous inkjet’s 10 mm or more. But for the right set of applications, Miller saw promise in cartridge-based thermal inkjet. Even so, his first foray into this tech unfortunately left a lot to be desired.

“My first cartridge coder wasn't a touchscreen; it used a dial that wasn’t very intuitive for operators to use. But more importantly, the cartridge leaked profusely, and that caused a lot of problems because leaking ink got inside the coder and caused shorts. I probably had to scrap 1,000 or so filled bottles in the six months I was using that system because of those cartridges. Every bottle was money, so you can do the math on what I lost there.”

That failure led Miller to research new options—this time a Redimark TC12 thermal inkjet system that he planned to use on an application involving lot coding 100-oz. HDPE liquid laundry detergent bottles. He took advantage of the manufacturer’s 30-day return policy, and immediately was impressed by the ease of set-up. The machine was up and running in 45 minutes, a process that can take from hours to days depending on the coding and marking solution. He also noticed the small footprint; he was able to attach the system directly to the conveyor so it didn’t occupy any floor space, and stood less of a chance of getting jostled by the busy operators on the packaging line. But beyond the size and simplicity first impressions, two factors in the Redimark system’s favor stood out to Miller the more he began to put it through its paces.

“First, they have one of the most efficient cartridges I've ever seen. Their cartridge usually has 1% ink left in it when it goes down,’ Miller says. “A lot of other coders I may have 50% ink left in them. I've seen them at 80% and the cartridge stops working. I don't know what [Redimark] has done technology-wise to make their cartridges so efficient, but they have the best I've ever seen.”

Cartridge efficiency, in this sense, eliminates waste. For every cartridge he burns through, Miller loses so much ink, loses so many prints, and those prints turn into dollars because he has to then buy more cartridges for the coder.

“The other major factor is if you know how to operate a tablet, you can operate this coder. You don’t have to attend a training session to teach operators how to use it. If they know how to use their phones, they can use the TC12,” Miller says. “That saves me a lot of training time. I can teach somebody how to use a Redimark machine in 30 minutes and they're proficient enough to run it.”

Hiccups and aftermarket support

Miller did mention one issue with the Redimark coding and marking system upon its initial installation, but its quick resolution was what left an impression.

During the TC12 coder operation, Redimark released a new ink that Mill-Chem wanted to use and required a controller software update. Dean Hornsby from Redimark sent an updated software file to Miller, who downloaded it to a USB thumb drive, plugged it into the back of the tablet HMI portion of the system, uploaded it. “Their customer service is second-to-none”, says Miller. “I've been doing this for 27 years, and I've been through a lot of coders, some of which cost exponentially more than the Redimark and a lot of times when you have a problem, you call the manufacturer and it turns into a question of ‘How much money is it going to cost for a guy to show up to look at it? You're going to charge me $250 because you have to drive three hours just to come look at a machine?’”

Miller also appreciates the aftermarket convenience of Redimark’s online ordering and e-commerce delivery channel of replacement cartridges or wear parts.

“I just go onto the website and type in my code so they know which company it is. It's set up efficiently because it will hold the data for whatever credit card you use, and it knows my recent actions. ‘Do I want to order the same amount I ordered last time?’ it asks me. That’s helpful because it’s one less thing I have to remember.”

Packaging operations and the detergent line

As a typical SIOP conventional business, Mill-Chem’s customers supply it with necessary packaging materials, including bottles, caps, corrugated, and, of course, the proprietary formula for the product itself. For its part, Mill-Chem both manufacturers and packages the product--scores of pallets of between 700 to 1,200 bottles leave the facility daily. The fastest packaging lines reach speeds of 2,500 bottles per hour, though 1,700 per hour is more typical.

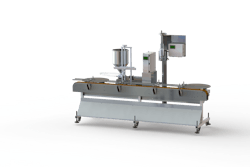

The specific packaging line using the TC12 thermal inkjet system, one of five filling lines at this facility, must be flexible given the variety of SKUs it handles. Still, it boasts an impressive amount of automation, starting with depalletization of the bottles, HDPE in this case. Bottles are first labeled, diverted either to a stretch sleeve label applicator for larger product or a pressure sensitive label (PSL) applicator. The stretch sleeve applicator is a Sleeve Co (now Fort Dearborn Co.) SL 1800 with vision sensors that operates from rollstock, and the PSL applicator is a pneumatic one from Quadrel Labeling Systems. Bottles labeled by either method are conveyed to a timing screw which feeds a 24-head filler from U.S. Bottlers Machinery Corporation.

The fill is clean enough so as not to require any rinsing or air drying before bottles are automatically sealed and capped on a SureKap capping machine with retorquer system. In the case of a sprayer used with many consumer cleaning products, hand application is necessary. To accommodate the aforementioned speeds of up to 2,500 bottles per hour in a hand closure application, Miller simply adds labor and the operation remains in-line. There’s enough conveyor footage on that portion of the line to accommodate several hand operators working in unison. Filled, sealed bottles are then coded and marked on the TC12.

“It depends on what the customer wants, but nine times out of 10, we code on a date of manufacture [DOM], the shift in which it was produced, and a batch number,” Miller says. “The batch number is linked to the chemicals that were used in the product’s formulation and manufacture, so it’s useful for QA. Or if we get audited, they'll grab a bottle and they want to be able to trace all the paperwork that goes with that bottle. That batch number carries all of that information throughout the supply chain, right down to its end use.”

Secondary packaging involves an automatic corrugated case erector, bottom sealer, and semi-automatic case packer from Combi Packaging Systems. Formats vary wildly, depending on the application. An operator hand fills the case, then it is conveyed to a top sealer by BestPack before hand palletization.

More recently Miller added a secondary TC12 coder to the case packing system downstream from the top sealer. Now that he’s nearly a year in with the two Redimarks, he plans to purchase a third TC12 to replace an existing continuous inkjet coder on another line.

“The cartridge doesn't leak, it’s efficient, it’s easy to use, it does what it's supposed to do, and it works as advertised,” Miller says. “That's what I'm looking for.” - PW