More flexibility, greater efficiency, less cost—those are what manufacturers say they want from people like Mike Grinager, vice president of technology at Brenton Engineering. The message was received loud and clear at Brenton, a builder of packaging and palletizing equipment in Alexandria, Minn. That’s why its newest line of side-loading case packers uses a decentralized, or distributed, approach to motion control—to take advantage of the intelligence and engineering found in today’s drives.

The result was a faster and simpler all-servo design. “We did everything we could to reduce the complexity of the machine,” says Grinager. “We took out the pneumatics, which was the most expensive aspect of the machine. And our engineers removed more than 200 moving parts, reducing costs by one-third.”

Moreover, the integrated servo motor and drive that made the design possible is half the size of a conventional servo system, which consists of a separate servo drive and motor. Consequently, the combined unit requires less space than even the smallest motors that Brenton engineers had used before.

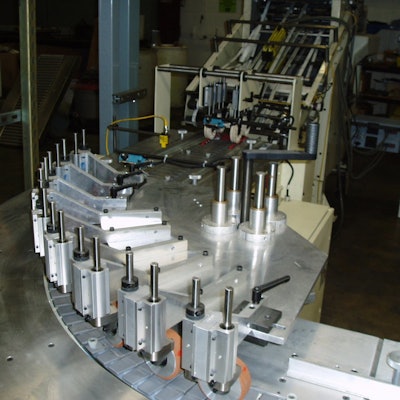

Each Bosch Rexroth IndraDrive Mi integrated servomotor/drive-amplifier unit mounts directly on the machine, outside the control cabinet. Because the units have been hardened and designed to dissipate heat outside the control cabinet, not only are the control cabinets 25 percent smaller, but they also consume fewer filters and 25 percent less energy for air conditioning. The motor-drive platform works with Sercos distributed I/O, an IndraMotion MLC motion logic controller and the IndraControl VEP40 human machine interface (HMI).

The distributed approach also permitted the Brenton engineering staff to eliminate clutter on the new case packer by taking advantage of new hybrid cables. Just one cable now runs from the new machine’s electrical cabinet, daisy-chained to each motor-and-drive unit to provide both power and communications. The hybrid cables reduced the cabling on each machine by about 80 percent, says Grinager.

“Our machine has a cleaner appearance without all the wires running to and from the electrical cabinet,” Grinager says. “Because of the small integrated motor-drive units and fewer cables, the machine has a walk-in design that allows easy access for the operator to clean and maintain it.”

Besides reducing the overall footprint of the machine, another advantage of decentralizing is less cost, usually about a third less, according to Abdulilah Alzayyat, product manager at Bosch Rexroth. These savings come from less cabling and less energy consumption. Not only is less cooling required in the cabinet, but modularity and daisy-chaining also permit recouping energy losses as the motors decelerate. “If one axis is breaking, you can use that energy to power a second axis that is accelerating,” says Alzayyat.

Other advanced features available are multi-Ethernet-based master communications, additional distributed field-line I/O, IEC 61131-3-compliant motion logic in the drive, and safety zonestechnology. “Our distributed motion controllers have optional safety onboard,” notes Alzayyat. “So, you can either have safety I/Os going directly to each axis to create separate safety zones, or you can have one central safety zone that includes the complete system.” One example: establishing a number of safety zones in a packaging machine. With these zones in place, an operator can stop a section independently of the others to clear a misfeed or perform some simple maintenance while the rest of the machine continues to run.

Two questions, not one

The question of whether to decentralize is not always a straightforward one, especially in sophisticated motion-control applications. The reason is that these applications often require a high degree of synchronization, which means that, besides power conversion, control is also an important aspect of the calculus. Consequently, the question about whether to centralize or distribute is actually two questions—one about power conversion, and the other about control and communication.

In both cases, engineers must weigh both the advantages and limitations of distributing and centralizing. When it comes to the drives, a smaller electronics cabinet and the savings on cooling and cabling costs are certainly powerful motivators to decentralize. “But you have to keep in mind that your electronics are now subject to the same vibration and other ambient conditions as the motor,” notes Craig Nelson, a product manager at Siemens Industry Inc. in Norcross, Ga. “Your electronic components must not only have a higher industrial-protection rating but also be of a higher quality.”

Decentralization, moreover, tends to make the most sense in low power ranges, usually less than 5 kW in servomotor applications, according to Nelson. As the power rating exceeds that threshold, the drives begin to become too big to be put on a motor in many applications.

Power also limits the selection of motors available for the decentralized approach in another way: Bigger motors generate much more heat than their smaller siblings as they decelerate. “Although we have technology that goes between the drive and motor to handle this heat, it is for smaller axes,” notes Alzayyat at Bosch Rexroth. He says that more research is necessary for developing suitable heat-dissipation technology for large motors.

When it comes to control, Nelson at Siemens reports that many engineers are opting to centralize on one control unit, rather than distribute several smaller ones for each drives. “The higher-power microprocessors available today have several times the computing power of the microprocessors from a decade ago,” he explains. “Going from ten separate drive control processors to just one central controller is a lot more cost efficient and manageable.”

>> Just What is Distributed Motion? Click here to read how utomation vendors are devising ways to deploy networking technology to distribute motion control architecture throughout machinery.

Other considerations that can change the calculus are the number of axes being driven and the available bandwidth for sending and receiving signals across the machine. “If you spread things out, then you have the lag time of getting those signals from device to device, whether you do that over a network or a backplane,” explains Nelson. “In general, the more axes that you’re coordinating, the more going toward a central control tends to make sense.” In these cases, processing directly on a high-performance processor tends to be the quickest way of processing the signals to coordinate the motion.

Asking both questions pays

Taking the time to consider whether to decentralize both control and power conversion can pay handsome dividends, as management discovered at Arandell Corp., a magazine and catalog printer in Menomonee Falls, Wis. On the recommendation of systems integrator FASTechology Group of Glen Carbon, Ill., Arandell decided to centralize control and distribute drives on three machines that it had retrofitted in the bindery.

Because the 30-year-old machines were mechanically sound, FASTechology upgraded them to add much-needed functionality and flexibility, yet retain integrated control and communications. The key goal of the project was to implement on-the-fly phasing between the motors driving the multistage conveyor on each machine, so the conveyor between operations could be adjusted while the machine was running.

Before the retrofit, the two sections of the conveyor were driven by one motor equipped with a planetary gear. To generate the desired flexibility and control, FASTechology replaced this motor with two motors, and the planetary gear with an electronic lineshaft from Siemens. They also specified Siemens’ Sinamics S120 drives and its Simotion D drive platform, which is now the common interface for the entire bindery.

FASTech’s engineers put the dynamic drives on the motors and consolidated motion, logic and drive control into the Simotion D platform. “The Simotion architecture, with its integrated motion controller and PLC controller, allowed us to perform advanced motion control along with normal PLC level logic,” says Jeff Mills, FASTech’s vice-president of engineering.

The result was greater control over transfers between the two sections of the machine. This not only made the transfers smoother over a greater range of speeds, but also improved throughput by 20 percent. The greater flexibility makes the machine easier for operators to modify. Mills also reports that the modularity of the drives and controls has allowed his engineers to apply the functionality developed for this machine elsewhere on similar retrofits.

A Measure of Modularity

Many machine builders are finding that mixing centralized control with distributed drives can help them to generate a measure of modularity in their product offerings. “The big challenge for machine builders today is that their customers typically want something slightly different,” explains Corey Morton, director of technology solutions at B&R Industrial Automation Corp. of Roswell, Ga. “They have to be able handle some level of custom requests on almost every order, which means that they must design their machines to do that easily.”

In this environment, a totally centralized approach is often not cost effective because the builder may need to invest engineering resources in changing the contents of the cabinet whenever capabilities are added or removed. These changes may also affect the cables running from the centralized cabinet to the various sections of the machine. “It’s very difficult for machine builders to be cost competitive, yet do a lot of engineering on every machine that goes out the door,” notes Morton.

To permit customization with minimal engineering, therefore, many machine builders are offering custom features as pre-engineered modules that plug into a base unit containing the machine’s core components. Because the core software and hardware will be the same in the machine regardless of the selected options, all hardware not part of the base machine design can be decentralized in the optional module.

>> Motion: How to Decide When to Distribute Costs. Click here

One machine builder adopted this modular strategy when it developed the next generation of its rotary-stretch blow-molding machines for producing polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles. Because this generation can have as many as 36 blowing stations, each capable of producing 2,250 bottles per hour, the company’s engineers designed the stations as modules. Besides offering the flexibility necessary for customization, the modular approach has also allowed the company to adopt what it calls assembly-line production to control costs.

The engineers laid the groundwork for generating this modularity when they replaced the pneumatic and belt drives with electric direct drives from B&R to improve the machine’s speed, precision and power consumption. Torque motors replace belt drives in turning the various positioning wheels in the machine, and specially designed tubular linear motors replace pneumatic devices in actuating the stretching rods in each station. An X20 System central processing unit (CPU) from B&R serves as the module’s controller, and the inverters come from B&R’s ACOPOSmulti series. Because the machine builder could install the inverter on each stretching station, it could produce the entire station in advance, test it, and parameterize it.

In this case a mix of centralized control with distributed drives proved the smartest solution of all.