The product fraud and counterfeiting threat is complex and extremely interdisciplinary. This is one reason it is such a growing threat and why the FBI calls it “the crime of the 21st century.” The challenge of selecting effective countermeasures is that criminals can be very adaptive and have a huge financial incentive to develop ways around security systems.

While there may be a slew of new or pending regulations, corporate leaders are realizing they need to tackle the threat from counterfeiters for simple business reasons. Counterfeit product and product-related fraud is creating current vulnerabilities that expose the business to tremendous risk of lost sales, recalls, or legal liability. These vulnerabilities are amplified by the global economic recession where protective countermeasures may have been reduced at the same time that counterfeiters have become more aggressive.

There is a need and a trend for corporations to take a more holistic and strategic approach. While packaging managers are often assigned to implement an anti-counterfeit plan, their task is usually to pick a packaging countermeasure and hope for the best. This is due to the lack of clear strategic direction from executives or even information such as simple risk assessments. Suddenly, packaging managers must be both tactician and strategist for the entire enterprise. Fortunately, risk mitigation is not completely alien to packaging professionals.

The base process of analyzing counterfeit product risk and selecting effective countermeasures should be familiar to packaging professionals. For example, a packaging professional may be responsible for the shelf life of a food product. But the first step to double the shelf life of a food product is not to just double the thickness of the package. The package designer must first understand the nature of how the products spoil (food science and biology), the product environment (chemistry and physics), the performance characteristics of the package (material science), and how these all interact (packaging science). Only then can a logical and efficient packaging design be tested and produced. Similarly, the selection of an effective anti-counterfeiting packaging component requires a multidisciplinary approach, but with some new disciplines based on the behavioral sciences that are focused on the details of the fraud opportunity.

Behavioral sciences and criminology primer

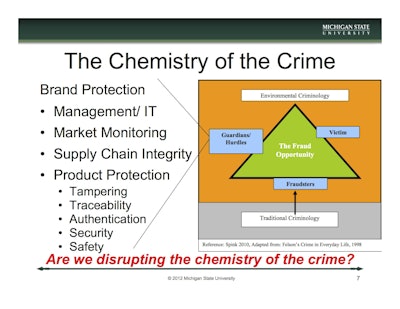

A key in the interdisciplinary approach to anti-counterfeit strategy is found within behavioral sciences and criminology. By understanding the root crime opportunity, companies and law enforcement authorities are able to identify why a crime took place or why a criminal might act. The application of Situational Crime Prevention is the Crime Triangle (see chart). The Crime Triangle requires three elements for a crime or the potential of a crime to occur. These are a victim (e.g., consumer, retailer, brand owner, etc.), a criminal, and the absence of a capable guardian or hurdle (e.g., inspectors, investigators, and traceability or authentication components).

As companies grow and their brands become more recognized, the victim side of the triangle will increase equating to a higher fraud opportunity. Regarding the criminal side of the triangle, there are a near-infinite number of criminals who may find counterfeiting opportunities. They are also difficult to deter because they are adaptive, creative, intelligent, resilient, clandestine, stealthy, and actively seeking to avoid detection. After a fuller understanding of criminals and victims, the main focus for brand owners should be on the guardian and hurdle side of the triangle. This will lead to the selection of countermeasures, including testing protocols and packaging tactics, which will effectively reduce counterfeiting opportunities.

Regulations, standards, and certifications

Another key to understanding the counterfeiting threat is common terminology. Standards and certifications are needed to provide common definitions and improved understanding. The International Standards Organization (ISO) created Technical Committee 247 on Fraud Countermeasures and Controls (TC 247). This group is specifically focused on fraud related to “material goods.” The group has begun to create management standards, which are general ways for securing systems. The group also is creating a Terminology document to assist in global harmonization. A related standard that is helpful is ISO 31000 Risk Management. Other groups are also involved in supporting different aspects of standardization such as the U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP), the North American Security Products Organization (NASPO), the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), and Global Standards One (GS1) among others. These types of standards can lead to a certification of compliance.

There are also a variety of regulations related to counterfeiting. While necessary, there has been an over-emphasis on meeting regulations that haven’t been fully defined with respect to their application. When a new regulation is passed, invariably suppliers scramble to maintain their competitive edge by developing new solutions. Brand owners also work to interpret the regulation so they can efficiently meet its requirements. Unfortunately application requirements of new regulations typically are not finalized quickly. For example, the 1987 Prescription Drug Marketing ACT (PDMA) is still in the process of having its traceability requirements defined. The California State Board of Pharmacy also pursued this but continues to delay e-pedigree implementation. Suppliers and brand owners alike initially scrambled to prepare to meet both regulations.

Another example is the 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Although there are some well-defined product fraud statements in the act, and FDA finished the documents early, the guidance documents that define implementation have been delayed for months. The focus on meeting new regulations and certifications creates an initial sense of urgency and decision makers are generally not conditioned to wait. Ironically, waiting is one way to efficiently meet the regulations without making costly missteps. But at the same time, businesses cannot afford to ignore the existing risks from counterfeiters.

As simple as it may sound, remaining focused on protecting the business is an effective strategy. Regardless of PDMA and FSMA, pharmaceutical and food companies are currently exposed to immense vulnerability from counterfeiting, diversion, smuggling, cargo theft, organized retail theft, product fraud, and food fraud. While ultimately meeting these regulations is important, protecting the business is more urgent and actionable. As with all emerging business strategies, the challenge is how to get top management buy-in.