Patients and caregivers alike appreciate medications with packaging that is easy to open and use. Ease of use is also considered the cat’s meow for veterinary packaging.

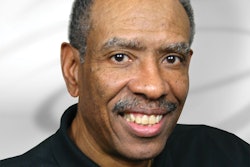

Obvious as that sounds, it’s not always the case. The packaging for a popular liquid flea-and-tick treatment for pets serves as a good example, according to Dr. Rae Ann Van Pelt, DVM and co-founder of 21-year-old Family Pet Animal Hospital in Chicago. “First, you have to open and remove an application tube out of a blister pack,” she explains. “Then there’s a rigid, triangular plastic tube that is only hard on one side. You can’t peel the softer portion of the tube off because you have to pour the medication onto the dog through a little spout once you’ve broken a little perforation on the applicator tip. The liquid tends to get all over your hands, and the treatment itself is a chemical that you don’t want on your hands. You have to make sure you get the full dosage printed on the package. Most pet owners are wary about therapeutic-type chemicals, and they get upset when they get it on their hands.”

Family Pet Animal Hospital employs 45 people. In addition to an on-site pharmacy, the practice provides surgical and ultrasound procedures, and hospitalization for illnesses, particularly geriatric care. It serves more than 6,000 “patients” annually, including cats, dogs, rabbits, ferrets, and other small mammals. Family Pet personnel treat pets with various prescription vaccines, solid and liquid medications, and nutritional supplements.

Van Pelt says, “We order vaccines, medicines, and nutritional supplements from multiple companies and through our distributor. We sell only prescriptions or supplements that say ‘for veterinary sale only,’ as we do not have a retail license.”

Packaging perspectives

From Van Pelt’s perspective, one of the most significant differences between physicians treating humans compared to doctors of veterinary medicine is “that in human medicine, doctors are well-educated in one specific area, whereas a veterinarian is more of a generalist who needs to understand the ‘big picture’ in extreme detail.”

Asked about the difference in packaging for medications used in the treatments for humans and animals, Van Pelt notes, “A majority of the drugs that we use are human drugs. One of the things that we are at the mercy of is that the tablets are made for the size of a human. So, we know we can’t be exact, and we do the best we can. For crucial medicines, we use compounding pharmacies, such as Braun PharmaCare, a human pharmacy based in Chicago that is also licensed in veterinary compounding and can make smaller milligram-strength capsules, liquids, or chewable treats for us. They also make some transdermal ointments applied into the ears of a cat, for example, which provides an option for patients whose feline will not take a treatment any other way.”

Like many animal hospitals, Family Pet has a pharmacy, but Van Pelt explains that it is illegal for a veterinary hospital to act as a dispensing pharmacy for something that’s already been compounded. “We can dispense things that we receive from a distributor directly to the client, but we cannot give them to middlemen unless we have a pharmacy license,” she says.

Packaging ‘pet peeves’

Family Pet typically receives pet treats in blister packs, and liquid meds and capsules in traditional brown vials. Most require no refrigeration.

Similar to the flea-and-tick treatment mentioned above, Van Pelt is often frustrated by packaging such as the glass vial used for one particular brand of morphine derivative. “It’s a human product that requires you to break off the top of the glass vial. Then we have to draw out the whole drug product at one time. In veterinary use, we usually don’t need all of it, so we’re taking a syringe and withdrawing just the amount of cc’s we need. The problem is that it’s a controlled substance, and while the DEA does give you some fudge room because they know that you can’t be perfect, it’s a frustrating situation.

“If [the product manufacturer] put the liquid in a vaccine-like vial with a rubberized stopper on top we would have a much easier time dispensing it.” Van Pelt recalls that at one point, the product was filled into a vial that made usage much easier. “We were thrilled when it came in the other packaging, but then they went back to the glass vial.”

She explains that glass breakage isn’t a problem, although “some people are afraid of breaking off the top because they are not used to it. If you do it correctly, it breaks cleanly. Occasionally it doesn’t and then you’ve got all that liquid running around the bottom of the vial,” she says.

Advantix provides a package that Van Pelt says makes it easy to open and apply the flea-and-trick liquid treatment. “Advantix comes in a little plastic tube,” she explains. “You take off the cap and use the back end of it to puncture a little hole in the tube. Then you squeeze it out nicely on the pet. There is no mess. There is no spillage. It’s easy to use here in our practice, and it’s easy for pet owners to use to treat their pets.”

Mail-order concerns

Asked about mail-order medications, their legitimacy, and their packaging, Van Pelt warns that a well-known toll-free number pet med firm has been sued multiple times. “They are sending packages that are almost identical [to legitimate product packaging] but not 100 percent. The other thing is that you have to watch the expiration on the drugs. They are selling things that are about to expire. Some companies like Foster and Smith are very reputable. However, in order to dispense the medication to a patient that lives in Illinois, you must have a valid client-patient relationship, which means you need to have seen them within the last year. So these pharmacies have a pharmacy license.

“That upsets veterinarians because prescription meds provide one of the few profit areas for us, which is important because the margins for veterinary medicines are low compared to other professions. It’s taking away one of the things that keeps us afloat.”

Further packaging thoughts

Van Pelt also offered the following packaging insights:

• More packaging is beginning to come boxed and sized for dosing by weights where you sell things by the box. For example, Frontline typically comes in a pack with six treatments.

• Anti-vomiting drug Ceremia is a tablet and is typically administered for five days in a row followed by two days of rest. These treatments follow an injection at the office. “Prepackaging of the drug means we don’t have to have somebody in our pharmacy counting out pills, and we don’t need to purchase a vial,” she says.

• Another drug, Panacur, used as a deworming medication used to be sold as a powder within a large container. “We had little measuring spoons and had to measure it out and put it in little packets because the powder gets sprinkled on food daily for three to five days, depending on the dosing,” Van Pelt explains.

“It was very labor-intensive. Now it comes in premeasured packets for weight. That has made life a lot easier. It also makes pricing a lot easier because with the original Panacur, it was difficult to judge how many dosages we would get out of the big container.”