Ergonomics and packaging can be good news for machine builders and for their customers, says John Hunt, head of the Packaging Resource Center at 3M Co., St. Paul, MN. Hunt spoke at a mid-summer seminar on equipment safety sponsored by the Packaging Machinery Manufacturers Institute (Arlington, VA). In addressing the issue of the Occupational Safety & Health Administration’s proposal on ergonomics in the workplace, he encouraged PMMI members to add more ergonomic features to equipment.

Although the word “ergonomics” tends to scare some people, Hunt says it’s really simple. He pointed out an industry definition for it, “the science of fitting workplace conditions and job demands to the capabilities of the working population.” Plus he said it really amounts to a lot of common sense mixed in with some good science.

In essence, he said it involves the design of jobs, workplaces and equipment to eliminate or minimize excessive reaching, bending, twisting, lifting, pinching, pushing, forcing and squeezing actions by workers, along with awkward postures and, of course, manual repetitive motions. All of these ergonomic issues, Hunt says, “exist extensively in packaging operations.”

Later, he pointed out the benefits to a manufacturer whose workplace used good ergonomic design: improved morale; reduced fatigue, stress, pain and injury; and easier and more enjoyable jobs. Also, more people–from big men to petite women–are able to perform the same task, which is a fundamental objective of ergonomics.

Despite the allure of these benefits, too often management overlooks their value because they are “soft” benefits as opposed to bona fide cost savers. In effect, management says, “Show me the money!”

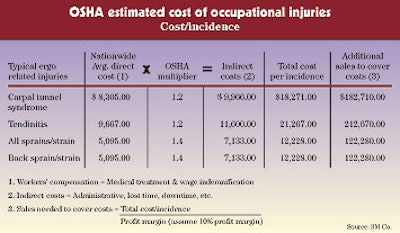

In response to that question, Hunt says the costs obviously vary from company to company, and he showed a 3M slide that displayed what OSHA calculates for direct and indirect costs in workplace injuries (Chart 1).

Among indirect costs, he cited absenteeism. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, workers with carpal tunnel syndrome missed 30 days of work, which was the lengthiest absence of any major type of job-related injury. Of these absences, Hunt says, 99% were due to repetitive motions, which is the leading cause of injury in packaging.

Loss of experienced employees and the costs of training new people is another indirect cost, as is poor product quality that results from either difficult job tasks or inexperienced help. And sometimes, he said, there is the cost of overtime pay to make up for production lost because of absences.

Hunt pointed out administrative costs involved with ergonomic injuries, including care by a nurse or other healthcare professional, accident investigation, processing of claims and potential litigation, the paperwork and meetings and the attendant management and supervisory time.

In addition, Hunt showed information about a pasta packaging operation that re-engineered its casing operation to reduce manual handling of bagged pasta. Although it was done primarily to reduce worker stress and not to increase production, the result was that some packaging output actually tripled. Sara Lee reported savings of $750ꯠ in workers’ comp costs and a reduction in workdays lost due to carpal tunnel syndrome when it modified line speeds and added material handling equipment and new procedures. Its reduction in workdays lost went from 731 days/yr to 8 days/yr, Hunt reported.

Closer to home, Hunt described a 3M liquid-packaging operation that saved $300ꯠ/yr when it added equipment and shifted from metal cans to film pouches. He also showed a picture of a worker positioned awkwardly and said that 3M was already investigating replacement equipment that would eliminate that problem.

But his ultimate message to machinery makers was to emphasize the ergonomic features of their equipment so that end users like 3M can use the features to help sell management on buying equipment that will be easier to use. “Ergonomics is very valid, and there’s no question that injuries result when it’s ignored,” Hunt concluded. “But [equipment makers] need to sell it, and so do I within my company.”

A-B goes its own way

Hunt was followed by Bob Morris, loss control manager for Atlantic Mutual (Atlanta, GA), who described how Anheuser-Busch, St. Louis, plans to oppose the OSHA ergonomics program. In concept, A-B put a safety program in place two years ago, using 1991 as the base year.

“Ergonomics is a tool to improve productivity through employee comfort and reduced fatigue,” the company stresses. “It is not a tool to reduce injuries.” With strong support from management, A-B instituted the MoveSmart Safety Training Program that is said to be based on sports medicine, ergonomics and even the martial arts. Its goal is the proper conditioning of employees to prepare them for their work. Employees with poor conditioning, says the program, are at a higher risk for injury.

The results of the A-B program (Chart 2) are eye-popping. Compared to the base year, total injury incident rate has fallen from 17.83 to 8.39 this year. Even more startling, the rate of disabling injuries is down by 80%.

A-B’s main problems with OSHA’s ergonomic proposal are two-fold: it sees total U.S. costs of $80 billion, not the $4 billion the agency estimates, and A-B feels that OSHA “assumes the only way to eliminate injuries is to eliminate work.”