Why is accessible packaging important?

According to U.K. consumer champion Which, a quarter of people regularly need help to open packaging and the same proportion have to rely or others more than they would like to (“Wrap Rage,” 2013).

Manufacturers of medical products face a dilemma when designing packaging, as the requirements for safety can compromise the accessibility of the packaging. Packaging must protect a product from physical damage, contamination, loss of product and tampering, without making the packaging too difficult to open. The task of opening packaging requires both a cognitive process and a physical process.

The cognitive process requires a person to recognize the location of openings on the packaging and to understand what technique or hand motion is required to get into the product itself. The physical action of opening the packaging usually requires some strength and dexterity in the hands and fingers. If users have impaired cognitive, visual, or physical abilities as a result of a medical condition, a disability, or old age, the task of opening packaging can be a major inconvenience. People with severe symptoms of a condition can be reliant on medication to be able to live their lives independently, but the severity of their symptoms often makes it difficult for them to open the packaging that contains their medication.

Inaccessible packaging can have many consequences to consumers and manufacturers, including reduced patient compliance to treatment plans, and increased numbers of injuries caused by patient “work-around” methods. The survey carried out by Which on 2,000 consumers found that four in 10 people have hurt themselves while trying to open everyday goods, with almost all having resorted to the use of tools such as scissors, sharp knives, razor blades, or even hammers in order to break through packaging (“Wrap Rage”, 2013). By understanding how consumers’ capabilities are limited, and developing packaging accordingly, manufacturers can ensure accessibility for a greater proportion of consumers and reduce the risk of negative consequences.

Millions of people across the world are diagnosed with conditions that can affect cognitive and/or physical abilities, including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, blindness, or mental disorders. Many conditions are more common in older users, with disabilities affecting almost half (49.8%) of the current U.S. population aged 65 or over (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). With an aging population, the demand for accessible packaging will continue to grow, and manufacturers will be put under increasing pressure to understand the limitations of their consumers.

How can we learn from people with impairments?

By carrying out research into the abilities and preferences of people with cognitive and physical impairments, manufacturers will be able to understand the limitations of consumers and design more accessible packaging for the future. We can begin to build a picture of the difficulties people experience with packaging by looking at consumers with particular impairments.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological condition characterized by symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, and slowness of movements. As well as affecting physical abilities, some cognitive impairments can result from Parkinson’s such as distraction, tiredness, and impaired memory. There is published data to show that people with Parkinson’s have impaired dexterity (e.g. Proud & Morris, 2009), however, there is little data showing how this reduced function affects people when opening packaging.

Medical Device Usability (MDU), a usability consultancy based in Cambridge, UK, carried out an explorative study to investigate the capabilities of people with Parkinson’s disease. The data collected provides valuable new insights from people with limited capabilities about the accessibility of current medical packaging. Although this initial study has a small sample size and does not represent all consumers with impairments, it does show that simple usability tests can generate valuable information that can contribute to a better understanding of accessible packaging for manufacturers, and demonstrate the importance of user-centred design.

How can we measure the capabilities of people with impairments?

A study was performed by MDU on a sample of five people with moderate to severe Parkinson’s, three caregivers, and three healthcare professionals. The study collected data using four different methods:

1. Anthropometric dimensions and strength capabilities

An Anthropometer was used to measure hand length and breadth for all the participants. Strength capabilities such as hand grip strength and various pinch strengths were measured using a hand grip dynamometer or a pinch gauge. Measurement technique followed the guidance provided by Adultdata: the Handbook of Adult Anthropometric and Strength Measurements (Peebles & Norris, 1998). The measurements of participants’ hands showed that participants with Parkinson’s had weaker average fingertip pinch strength than the participants without the disease, but did not have impaired whole hand grip strength or lateral pinch strength (the pinch strength between the thumb and side of the index finger, in the way that a person holds a key to unlock a door).

2. Cognitive, visual, and physical abilities

Abilities were assessed by use of a questionnaire. The majority of questions used Likert scales to evaluate the level of difficulty participants experience with daily tasks. Participants rated how difficult they found the task on a five-point scale from “no difficulty” to “I cannot do it.” The physical tasks were focused on the use of the hands rather than the whole body, as interactions with packaging usually involve only the upper limbs. The questionnaire revealed that there was a difference in physical and cognitive abilities between the participants with and without Parkinson’s, but there was no difference between the participant groups in terms of visual ability. The participants without the disease said none of cognitive or physical tasks would cause them difficulty, whereas the participants with Parkinson’s said over half (51%) of the tasks would cause them at least some difficulty.

3. The outcomes of package opening tasks

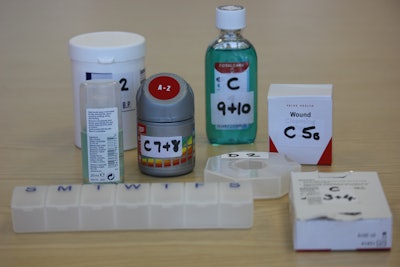

Participants carried out 26 package opening tasks on a range of different items:

• Twelve medical and health products including a syringe, a toothbrush, a bottle of mouthwash, a powder sachet, and a blister pack for pills.

• Five pill containers. Variations included a capsule key ring, a Monday-to-Friday compartment tray and a rotating dispenser. These reflected typical packaging of oral pills in the home.

• Six fastening methods of portable items, including a Velcro strap, a zipper, a magnetic clasp, a side-release buckle and a press stud or popper. Fastening methods were tested to represent the “packaging” of alternative types of Parkinson’s medication, such as infusion pumps or injection devices.

The outcome of each opening task was recorded as either succeeded without difficulty, succeeded with difficulty, or failed. Participants without Parkinson’s did experience difficulties with 7% of the opening tasks, however, the proportion of tasks that caused participants with Parkinson’s difficulties was greater (23%). Participants provided subjective ratings for the cognitive and physical difficulty of the opening tasks using a seven-point scale ranging from very easy (1) to very difficult (7). Participants with Parkinson’s recorded more cognitive and physical difficulties during the tasks than the other participants. The physical aspect of the task was rated as more difficult than the cognitive aspect.

4. General preferences of packaging methods

Participants were encouraged to make suggestions for improvements that would make packaging more accessible for themselves or others people with impairments. These insights were used to guide recommendations in the following sections.

What makes packaging difficult for people with Parkinson’s?

By analyzing and compiling the data collected from the study, the origins of participants’ difficulties were exposed. Figure 1 shows the key aspects of the task or packaging design that affected participants’ ability to open the packaging. The items that participants found easy to open are shown on the right side of the table and the items that participants found difficult to open on the left. A minus sign represents a factor that negatively affected the accessibility of the packaging, and a plus sign represents a factor that positively affected the accessibility of the packaging.

One package opening task that caused 4/5 participants with Parkinson’s difficulties was opening a small needle capsule with a twist-off cap. The most limiting feature about this item was its small size. Although there were some instructions for opening the capsule, the size of the item meant most participants did not see these instructions. The capsule offered little room for participants to grip onto the capsule, resulting in participants having to rely on their fingertip pinch strength and dexterity in their fingers to remove the lid. In addition, the capsule was encased in a paper cover, which required a reasonable amount of force to break. In comparison, one of the easier packages to open was a tub containing powder that had a simple lift-off lid. The tub was much larger than the needle capsule, allowing participants to use their whole hand to grip onto the sides. The clearly visible protrusion on the lid made it easy for participants to understand the opening method, and the action could be completed by pushing gently with the thumbs, without the need for finger dexterity or pinch strength.

One item that caused difficulties for participants both with and without Parkinon’s was a child-resistant bottle cap that required a push down and twist action. The cap was small, providing little space onto which the participants could grip. A reasonable amount of strength was required for push-down action, which became problematic when this action was required in combination with the twisting action. The small size of the cap meant participants had to use fingertip grip strength while carrying out the combination movements, which participants with Parkinson’s found difficult. The other child-resistant cap that was tested in this study required a squeeze and twist action. Participants found it easier to maintain the squeeze action as opposed to the push-down action while twisting the cap. The squeeze and twist bottle had a much larger cap than the push-down and twist bottle and provided good gripping areas. This allowed participants to use a lateral pinch grip and support the action with their whole hand, rather than use a weak fingertip grip.

How do we improve the accessibility of medical packaging?

By analyzing the data collected from people with Parkinson’s, the following recommendations can be made:

• Minimize use of the fingers, and provide larger grip areas

Participants with Parkinson’s struggle to open packaging that requires lots of dexterity or strength in the fingers. All the packages that participants found difficult to open in Figure 1 required strong fingertip pinch grips, which many participants were not capable of producing. However, when participants were able to use a lateral pinch grip rather than a fingertip pinch grip, fewer difficulties were observed. In this study, the participants with Parkinson’s did not have impaired lateral pinch strength, so when participants were able to, they gripped with item with a lateral pinch rather than a fingertip pinch. The design of the bottle inner seal and the powder sachet allowed for the lateral pinch grip, whereas the difficult to open items in Figure 1 did not. Mostly this was due to the amount of space there was available for the participant to grip onto.

Recommendations:

• Where appropriate, packaging should provide an opening tab or gripping surface that is large enough to facilitate the use of a lateral pinch, rather than a fingertip pinch

• Gather anthropometric measurements of consumers’ hands to help guide designs

• Avoid “over packaging” and explore alternative designs

Overall, the item that caused participants most difficulty was the shrink-wrapped, child-resistant bottle. To access the contents of the bottle, participants needed a large amount of fingertip strength to remove the shrinkwrap around the cap, and then push-down and twist on the cap to open the bottle.

Consumers with impairments can become frustrated with items they perceive as “over packaged,” and may seek out alternatives from different manufacturers. By embracing the use of alternative packaging designs, manufacturers may be able to avoid these problems and benefit from having accessible packaging. The alternative child-resistant bottle that required a squeeze and twist action was found to cause fewer difficulties than the bottle with the push-down and twist cap. Although both of the simultaneous opening actions were challenging for participants, the design of the squeeze and twist cap was the more accessible option. Getting feedback from consumers is crucial when determining the most accessible child-resistant packages, and manufacturers can benefit greatly from the insights of consumers with impairments.

Recommendations:

• Use a large-diameter cap to allow for a lateral pinch grip

• Provide an easy-to-grip ridged surface

• If possible, use a cap that avoids the need for two simultaneous actions (such as a push-down action in combination with another action)

• Investigate alternative designs for inaccessible child-resistant caps, such as the squeeze and twist method

Minimize the strength required for access

The physical demand required by consumers to opening packaging must reflect the capabilities of impaired consumers. By collecting anthropometric strength measurements such as grip and pinch strengths, manufacturers will have a better understanding of the limitations of the consumers, and will be able to produce more accessible packaging solutions. The strength required to open packaging can be the result of a number of design features, including the type of seal, the type of adhesive, and the packaging material. In this study, the plastic shrinkwrap covering the bottle cap was thick and difficult for participants to tear open and required a large amount of fingertip pinch strength. The syringe casing required participants to have enough strength to pull apart two sides of the casing, which were held together with an adhesive. The strength required for this task caused some participants difficulties when gripping the tabs with their fingertips.

Recommendations:

• Gather data on strength capabilities of consumers’ hands to help guide packaging design

• If fine finger actions are required to open packaging, the strength required must be minimal

• If whole hand actions or thumb actions are required to open packaging, the strength required may be greater than for fine finger actions, but should still reflect the strength capabilities of the most limited consumers

• When consumers are required to peel apart packaging, minimize the use of tough adhesives

• When consumers are required to tear open covers or remove wrapping, use thin and easy-to-tear materials

Use instructions and opening features to help consumers

Many of the items tested on people with Parkinson’s incorporated an opening feature or some form of instructions in their design. For example, the powder sachet had a notch in the packet to indicate where on the packet to tear, the shrink-wrapped bottle cap had a perforated area, and the plaster had tabs to grip onto to pull apart the casing and the child-resistant bottles had written instructions on the caps.

When these features were applied well, such as on the sachet or the squeeze and twist bottle, they helped participants gain access to the items. However, for some items, these features were not adequate to help participants opening the packaging. The perforations in the shrink-wrapped bottle cap were particularly unhelpful for participants, as they were not clearly indicated and did not reduce the physical effort required to remove the wrapping. Manufacturers must not underestimate the benefits of small design features such as highlighted perforations or simple instructions, as they can have a great impact on the accessibility of packaging. Further research is needed to help manufacturers understand how these design features are most successfully incorporated into packaging design.

Recommendations:

• Incorporate opening features and instructions wherever possible

• Ensure opening instructions are clear and obvious to consumers (using words, symbols, or images where appropriate)

• Make opening features obvious to consumers using color and other indicators

• Make sure the opening features adequately reduce the opening demands on the consumer

• Increase the size of opening features, especially opening tabs

• If one opening feature is not adequate, use additional features (eg. add an external red tab to the shrinkwrap for consumer to pull on to remove the wrapping)

The implications of accessible packaging

Commonly, opening and organizing medication is a task that patients try to do themselves, even if they have severe physical symptoms. As independence is a key factor to quality of life, it is crucial that people with medical conditions are able to access their medications without major difficulties. Patients who are unable to open packaging themselves may be less likely to adhere to their medication regimen, which will result in inadequate management of their medical condition.

For people with medical conditions who live alone, access to medication is vital and should be achievable without the need to resort to tools that may lead to injury. The investigation carried out by Which in 2013 suggested that over a two-year period, 25 million people in the UK hurt themselves while trying to open packaging, with the majority of consumers needing to resort to the use of scissors (89%) or knives (66%).

Both the Which survey and the MDU study conducted on people with Parkinson’s revealed that opening packaging caused difficulties for people with no impairments, not just people with impairments.

The study conducted by MDU was small and did not assess the needs of all people with impairments, however, it demonstrated how the capabilities and preferences of people with impairments can be captured by using usability testing methods. Parkinson’s is a condition that affects people in many different ways and symptoms vary from person to person. Further investigation using a larger sample of people with PD is needed in order to gain further understanding of the capabilities and preferences of this group of consumers.

Developing accessible packaging is an investment for manufacturers, as satisfied customers can result in increased profits and a well-respected brand identity. A product that is known for being easy to use and accessible for people with impairments is likely to be favoured by consumers who have difficulties with packaging. With an aging population, the number of consumers who have difficulties with packaging will continue to increase, meaning more consumers will be unable to access their medical products.

References:

Proud E.L., Morris M.E., 2010, Skilled Hand Dexterity in Parkinson's Disease: Effects of Adding a Concurrent Task, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Volume 91, Issue 5, Pages 794-799.

US Census Bureau, 2010, Americans with Disabilities, Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Peebles, L., & Norris, B., 1998.Adultdata: The handbook of adult anthropometric and strength measurements—Data for design safety. London: Government Consumer Safety Research, Department of Trade and Industry.

Which, 2013, “Wrap Rage: Inaccessible Packaging.”

Author Marie Davis works at Medical Device Usability, a Human Factors Consultancy based in Cambridge, U.K.. She recently carried out some research into the accessibility of packaging for people with Parkinson’s disease, which provides valuable insights into the capabilities and preferences of people with reduced motor skills. Research into user-centred packaging design often focuses on the difficulties faced by elderly patients, but very little data is available about the difficulties experienced by patients with physical or cognitive impairments. This article is based on an exploratory usability study of existing medical and health packaging and provides data on the strength capabilities of people with Parkinson’s, their preferences for packaging, and objective and subjective data from simulated package opening tasks. It also identifies the causes of patient difficulties, suggestions for packaging improvements, and a discussion about the implications of accessible packaging design. MDU may be reached at Medical Device Usability Ltd., Human Factors and Usability for Medical Technologies, on 011/44 (0)1223 214 044.