Nestlé U.K. has just launched what it’s calling the first self-heating can of prepared coffee. The 211x206 three-piece steel can has an internal volume of 330 mL (11.16 oz). But to make room for the heat-generating chamber that consumes a significant portion of the can’s interior, the can holds just 210 mL (7.1 oz) of liquid. Available in test since late August in central England, the Nescafé Hot When You Want coffees come in two flavors and sell for about £1.20 (U.S.$1.75) in supermarkets, convenience stores, and gas station snack stores.

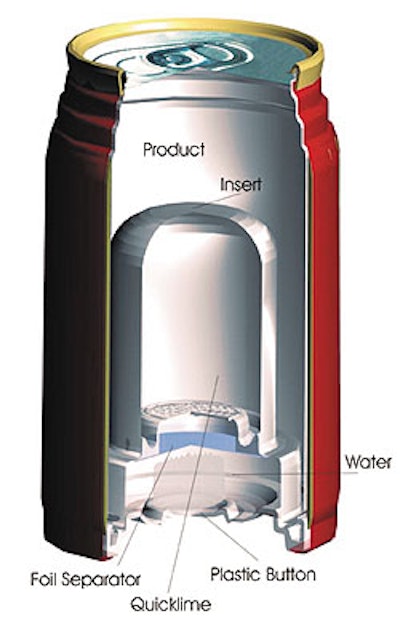

Designed for consumers on the go, the can has a conventional ring-pull top. Heating is activated by pushing in a button on the base of the can. This produces a chemical reaction between water and quicklime that are contained in separate compartments in the can base. After three minutes, the coffee is heated to 60°C (140°F). Insulating materials keep the consumer’s fingers and lips from being burned, says Nestlé.

According to Nestlé UK commercial project manager Graham White, the potential for self-heating cans is enormous. He reckons that if just half of the 100 billion hot drinks consumed in the UK annually were in self-heating cans, sales could be in the range of 500 million units.

The brains behind this unusual can technology since 1996 has been Thermotic Developments of Manchester, England, represented in the United States by Thermotic Developments Ltd. (New York, NY). The company remains at the center of the assembly process behind the self-heating can.

But manufacturing begins at the Worcester, England, plant of Crown Cork & Seal (Philadelphia, PA). There the steel can body is welded and an unusual steel bottom, drawn to a depth of 70 mm (2 3/4”), is seamed on. This becomes the chamber that holds the heat-generating components. Crown also makes the ring-pull ends and ships cans and ends to a Nestlé plant in Ashborne, England, for filling and application of the ring-pull end.

One other key vendor is Corus (London, England), which supplies the steel Crown uses to make the can components. The steel for the heat-generating chamber has polyethylene terephthalate laminated to both sides via Corus’s Ferrolyte® technology. Soon the PET will be applied more economically as a direct extrusion, rather than a lamination, through a next-generation technology that Corus calls Protact®.

On to filling

Once Crown has applied the bottom end to the body of the can, filling is done on a Nestlé canning line that’s also used for various condensed and evaporated milk products. According to Thermotic Developments’ Matthew Searle, changes required on the line involved only modest adjustments to chucks, rollers, and lane guides.

After filled cans are retorted, they leave the Nestlé plant in Ashborne and are shipped to a Thermotic Developments plant in Nottinghamshire, where a complex sequence of filling, sealing, and decorating unfolds. First, 70 g (2.47 oz) of slaked lime, or calcium oxide, are filled volumetrically into the can’s heat-generating chamber. Next, an injection-molded PP plug from the U.K. division of The Plastek Group (Erie, PA) is mechanically fed from a bowl and pressed in over the lime. This holds the lime in place and prevents it from interfering one step later when a foil membrane is heat sealed on. Once the foil is on, the lime is hermetically sealed in. To be extra sure, a bead of wax is placed around the edge of the foil. “It’s sprayed on like glue from a hot-melt gun,” says Searle.

Then, a volumetric liquid filling station deposits about 20 mL (0.68 oz) of water on top of the foil. An injection-molded polypropylene piece is pressed on to finish the can bottom and hold the water in. In the center of this bottom piece is a button. When consumers press it, the button punctures the foil and begins the heat-producing chemical reaction between the water and the lime. When the water is no longer visible through the translucent PP piece, the can is shaken gently and then turned right side up and left for three minutes. The coffee is then ready to drink.

Plastek supplies the one-piece PP end with the activating button. Searle describes it as “enormously clever.” In addition to providing the means by which heating is triggered, “This plastic end also has a venting function built into it,” says Searle. “If internal pressure gets too high as heat is generated, the pressure is released through this venting mechanism and out along the sidewalls of the can.”

Three more pieces

Three more pieces are added at the Nottinghamshire plant. The first is a single-faced piece of corrugated that insulates the consumer’s hand from the hot metal. Currently these are applied manually. But a machine now on order will take cut pieces from a magazine and glue-apply them like labels.

Applied over the single-faced corrugated is a full-body oriented polystyrene shrink label from Sleever Intl., represented in North America by Sleever Intl., Inc. (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The 80-micron (3.2-mil) labels are gravure-printed in nine colors and are applied by an automatic SleeverMachines Powersleeve® system, also from Sleever Intl.

Finally there’s the lip protector, applied by hand over the top of the can so that the consumer’s lips aren’t burned. Injection-molded of PP by Plastek, it’s pressed on by hand.

And at what speed are cans sent through this rather complex process? Approximately 90/min. Searle is the first to admit that’s too slow, and he says it will be remedied when a new line is installed some time next year. That line, he projects, will require four operators and will run at about 600/min.

And the cost?

Unfortunately, Nestlé wouldn’t comment on the economics of this multi-component package, nor would the firm say much about why this particular self-heating can technology was chosen over others. But according to industry sources, Nestlé likes two things about this container. Made by an established can maker, it can be filled and handled like an ordinary can. Furthermore, it keeps lime-filled cans away from the filling line. “Filling lines have a way of eating cans occasionally, which could result in having lime or whatever all over the place,” says Searle. “And lime is not the nicest material in the world to have in a food plant.”

Though it’s just now reaching store shelves in England, the self-heating can has already begun to scoop up industry prizes. It won a bronze award in the Can of the Year competition at this year’s Cannex show in Denver. Upon that occasion, Gerhard Berssenbruegge, managing director of Nestlé UK beverage division, had this to say to CanTech International magazine:“The reaction from consumers who have already tried it has been phenomenally positive, and [retailers] are delighted to see a refreshing new category being developed by a brand leader.”