It was the kind of stacked-up, buzzing crowd that might have been expecting Julia Roberts or Brad Pitt. But instead of movie stars escorted to the dais by a phalanx of security guards, it was four of the Food & Drug Administration top drug packaging reviewers that commanded attention on Oct. 26.

By 8 a.m. that day, the mezzanine-level conference room at the Doubletree Hotel two blocks from FDA headquarters in Rockville, MD, was bursting at the seams. As the session’s first slides appeared on the screen and the coffee cups stopped clinking, what was unveiled was not a new Hollywood blockbuster but FDA’s new drug packaging “guidance.”

Actually, the container closure guidance had been issued the past summer. But the joint industry/FDA workshop on Oct. 26 marked the first time FDA officials had gathered to answer questions from an anxious industry.

The guidance—which for all intents and purposes means requirements—is used by companies whose packaging departments submit abbreviated new drug applications (ANDAs) and NDAs. The packaging sections of these applications have to include information on the resins, the containers themselves and data proving that things such as light, moisture and germs do not penetrate the package and ruin the drug.

The goal: faster approvals

The point of this packaging guidance revision (the current version was written in 1987) was to make it easier for drug packaging departments to know what FDA needs, and for FDA to gather the correct data the first time, so it can approve a new drug as quickly as possible.

“This guidance is much more comprehensive than the 1987 version,” said Eric Sheinin, FDA’s top drug packaging official.

By being more specific about what it considers “suitable for use” is one of the ways FDA made the guidance more comprehensive. In the 1987 guidance, FDA listed different packaging materials, but offered little input about what it would look for when that material was used with a particular drug form, be it solid, liquid or a spray. In most cases, the agency simply said the material had to be “suitable for the intended use.” There was little clarification of what FDA wanted to see on that score.

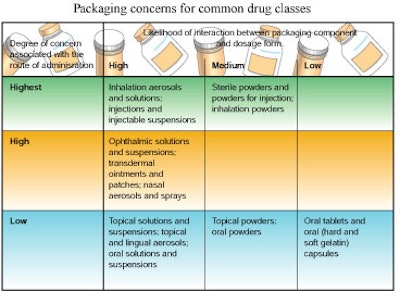

In the 1999 guidance, the FDA divides drugs by product forms, ranks each form in terms of the possibility of drug contamination via packaging (see below), and lists specific ideas on the types of proof-of-packaging-safety data it wants to see for each. Risk categories are based on two factors: the possibility of a packaging component leaching into the product and the route of administration of the drug. Based on that matrix, inhalation aerosols and solutions, and injections and injectable suspensions are in the highest risk category.

FDA wants more data

FDA wants to see more data for the “primary” packaging components intended for those drugs. That data requirement falls into categories such as how the packaging protects the product from light and moisture, tests that prove chemicals from the packaging won’t leach into the product and establishing quality control in the manufacturing process and other areas.

There was only a bit of murmuring about that ranking system. Deborah Miran, president of Miran Consulting, noted that manufacturers of generic drugs had tried to convince FDA to kick inhalation aerosols from the highest risk category.

An FDA official from the pulmonary products group popped up to a microphone and pointed out that it was the medical officers within his group who insisted that nasal sprays be put in the high risk category.

Generally, though, the ranking system and the data guidance earned plaudits. Kurt Trombley, senior packaging engineer for package development at Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Mason, OH, said the guidance “really clarifies” the suitability issue. “This is going to be extremely helpful to us,” he added.

Some quibbles

From the tenor of the questions and the buzz among attendees, it was clear that most drug packaging people felt much as Trombley did. There certainly were quibbles, though. Rich Hollander, manager of packaging services at Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY, and chairman of the PhRMA packaging work group, asked questions on behalf of PhRMA work-group members. Those questions indicated that some aspects of the guidance could be brought into sharper focus.

For example, Hollander asked for more clarity with regard to FDA’s desire to see “dimensional drawings” as part of a company’s submission on quality control. He asked whether the drawings had to show the “noncritical dimensions” of the package. For example, would a company have to include detailed engineering drawings such as the ones commonly supplied by component manufacturers?

In an interview after the workshop, Hollander elaborated by saying he understood that FDA wanted drawings for the critical dimensions of a package that affect the way a drug is administered. But he would have preferred to see the guidance expanded on this point to make clear that more complex, detailed drawings are required as a drug form climbs higher on the chart (Table 1).

Hollander asked for and received verbal confirmation from FDA officials on the dais that his understanding of the drawings requirement squared with FDA’s intent. But, of course, drug packaging people not present at the workshop did not hear that exchange.

DMFs can be tricky

There were also questions about what has to be included in a drug master file (DMF). A DMF contains the same kind of packaging data that a drug application does. The difference is that the DMF data is confidential. Typically, a DMF is used by a packaging supplier. The supplier would send a “letter of authorization” (LOA) to each of the drug manufacturers that uses its packaging component. When the drug company submitted its NDA it would reference the supplier’s DMF for information on whatever component was involved.

This procedure can prove tricky, especially if one DMF makes reference to other DMFs. A drug company might cite a DMF for its closure system. That DMF might cite a DMF for a resin in the closure. “It is not unusual to have to check 12 to 15 DMFs for a drug approval application,” said James Vidra, an FDA official.

He emphasized that the drug company submitting the ANDA or NDA, whenever it cites a DMF, must indicate to FDA in which section of that DMF the requisite information is contained. That is because some DMFs contain five to 10 volumes of data. Failure to indicate the appropriate section could significantly slow FDA consideration of an application. Similarly, the drug company’s failure to include a LOA when it references a DMF, or problems with the supplier’s DMF—for example, failure to provide an annual update—can also bring FDA consideration of an application to a halt.

Stability testing confuses

There was one item in the guidance that did cause major confusion: the requirement that companies conduct stability testing on capsules or pills that had been stored in a bulk container for more than 30 days. “That issue was not totally resolved,” said Art Jaeger, director of packaging development for Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, PA. “FDA was a little vague.”

The fact that packaging people appeared to have only minor quibbles with the guidance probably reflected FDA’s willingness to make changes. John Smith, an FDA review chemist in the office of new drug chemistry, said, “The message we tried to convey in the draft was not always the message that was received.”

One of the changes FDA made in the final guidance was to create a new category called “associated components.” It includes packaging components such as eyedroppers and dosing cups that are packaged separately and not stored in contact with the dosage form for its entire shelf life. The data that has to be sent in for associated components—safety and functionality are the big issues—are less cumbersome than for primary components but more complex than is required for secondary components.

A more substantial modification was FDA’s decision to remove from the guidance any mention of packaging data that has to be submitted when a company decides to change the packaging for a product already on the product. The 1997 FDA Modernization Act contained requirements telling FDA to make it easier for the industry to make “post-approval” changes. Section 116 of FDAMA was an explicit charge to FDA to provide “regulatory relief” to the industry, a concept that did not figure in at all to the “pre-approval” guidance.

So FDA pulled out the “post-approval” packaging guidance and put it on a separate track that has turned out to be much more bumpy. When FDA published a draft of the “post-approval” packaging guidance last June, the industry rose up against several sections. The final guidance was expected to be published by the end of 1999.

At the Oct. 26 meeting, Deborah Miran mentioned the post-approval guidance in passing, adding that she felt the agency did provide regulatory relief. FDA’s Sheinin, who was at the microphone, immediately thanked her and noted, with a rueful grin, that many in the audience would not agree with Miran.