One of the big buzzes coming out of the RFID applications conference in Washington, DC, in late September was news of the deal cut by the state of California and the drug industry on drug pedigrees. RFID, of course, is Radio-Frequency Identification, which is essentially a chip and antenna that can be programmed with product information more complete than that provided by bar codes. RFID requires special scanners to capture the data.

In late August, California agreed to delay imposition of the most onerous electronic pedigree requirement in the country, which was supposed to have gone into effect on January 1, 2007. In exchange for the delay of two years, drug industry companies agreed that all “pedigrees” accompanying drug packages as of January 1, 2009, would be both electronic and item-level.

That deal was then translated into legislation, which, at the end of September, was signed into law by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“This is huge,” emphasized Andres Botero, director of RFID program management at SAP (www.sap.com/index.epx), which works with 90% of U.S. drug manufacturers and has been involved in almost all the RFID pilots and rollouts until now. “Our phones have been ringing off the hook for the past month. The California action is galvanizing the pharmaceutical industry.”

A drug manufacturer would not have to use RFID to satisfy the California requirement; bar codes would work, too. “But RFID has an advantage because reading the tags doesn't require line of sight, as is the case with bar codes,” Botero added.

Bruce Hastings, manager of packaging engineering services for Eisai, the Japanese drug company whose main two products are Aricept and Aciphex, an Alzheimer's and gastrointestinal drug, was unaware of the California news until he heard Botero's presentation. Eisai's American subsidiary sells into California. “I was surprised to hear that,” he said. “We are very interested in implementing a pilot program testing both RFID and bar codes.”

It remains to be seen whether Botero's prediction about the California compromise sparking RFID item-level drug packaging turns out to be true. The conference, like others over the past few years, still provided a forum for both packagers and vendors who are taking a “tip-toe” approach towards RFID.

Some pioneers

GlaxoSmithKline has long been considered one of the faster moving drug manufacturers in regard to RFID. But Mark Shaefer, group director HIV, ID Medicine Development Center, called GSK's tagging of Trizivir, an AIDs drug, a pilot. Like Pfizer's tagging of packages of Viagra, Glaxo is also putting 13.56 Mhz tags on the item-level bottles. The pilot began in March. Shaefer said GSK wants to look at the data on the pilot before deciding if and when to put RFID tags on cases and pallets.

The bottles are tagged at a GSK manufacturing facility in Zebulon, NC, shipped to a distribution center, and then on to participating pharmacies, which include Walgreens and RiteAid. Shaefer emphasized the company has not seen enough data yet to make a decision on a next step.

Shaefer discussed some of the public opposition from community groups to GSK's initial decision to tag Trizivir. Those objections had to do with concerns about violations of privacy, particularly where those taking the medication might be “outted” by an RFID snooper. He noted that those concerns were stoked in part by a television commercial during the Super Bowl that had an airplane flying over a house and uploading residents' data off an RFID tag. He underlined the importance of educating pharmacists about taking the RFID tag off the bottle.

Interfering with tracking?

But Chris Hanebeck, lead RFID consultant for IBM Global Services (www-935.ibm.com/services/us/index.wss), said that from a drug manufacturer's perspective, dropping the tag after the consumer picks up the prescription in the pharmacy defeats an important purpose for having the tags on the bottles in the first place. In the case of a recall, the manufacturer would know, because of the RFID tags, exactly which lots at which drug stores needed to come back.

Now, pharmacies typically return many more lots than necessary just to be sure they return the “correct” lot. Moreover, with RFID tags on bottles in medicine cabinets, consumers could come back in to the pharmacy and have their vials scanned. One solution, Hanebeck suggested, to meet consumer privacy concerns, was a “clip-tag” where the pharmacist could clip off a part of the antennae on the RFID tag just before handing the bottle to the customer. That would leave a scanner range of less than a foot.

One consultant at the conference, who did not want to be named, doubted that California's move would drive RFID adoption. In her view, manufacturers will not make a stronger commitment to RFID until the Food and Drug Administration issues some kind of a ruling on what frequency tags should be used on biologics. “Once you get beyond solids, you have to worry about frequency,” she stressed.

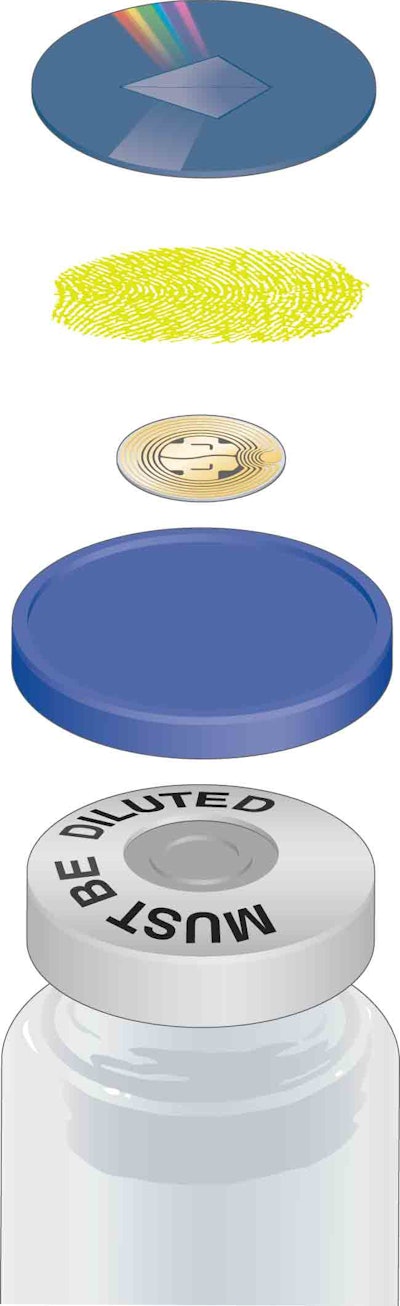

Eugene Polini, the customer technical support representative for West Pharmaceutical Services, Inc., (www.westpharma.com) also referred to manufacturers waiting for an FDA mandate. West has been strongly selling its Spectra RFID seals for vaccines and solutions, but to no avail. Polini admitted no customers have signed contracts yet. “This industry moves like a snail,” he said, referring to enteral drug manufacturers.