Pfizer’s announcement November 14 that it had successfully tagged its first lots of Viagra that day was an indication that some large pharmaceutical companies are moving ahead with RFID implementations, despite reservations which continue to stymie other industry players big and small. All lots of Viagra from Pfizer’s plant in France into the United States will have 30- and 100-count bottles and their cartons tagged starting on December 15, said Peggy Staver, director of trade product integrity at Pfizer U.S. Pharmaceuticals. She spoke at a November RFID conference for the pharmaceutical trade sponsored by the National Assn. of Chain Drug Stores and Healthcare Distribution Management Assn.

Pfizer is the first major brand-name U.S. drug company to implement RFID, although Staver admitted that the company’s one-product-only implementation is being made relatively easy by the fact Viagra is manufactured in only one plant and on only one packaging line. The company is using 13.56 MHz tags on the bottles and 915 MHz tags on cartons and pallets.

RFID readied at GSK

Bruce Cohen, director of packaging technology for GlaxoSmithKline, also said in an interview at the conference that his company was ready to start tagging one of its drugs, which he declined to identify. “We are almost there,” stated Cohen. “We are ready to turn it on.”

Cohen clearly tried to make it clear that GSK was honoring its commitment to the FDA, which in February 2004, agreed to give pharmaceutical manufacturers some breathing room to implement RFID tagging voluntarily. At that time GSK pledged that it would tag at least one product within 12-18 months.

Randall Lutter, associate commissioner of the FDA, told attendees, “From our vantage point today, it appears a voluntary approach may not be enough. At this point we have become concerned about the slow or inadequate progress [being made in] implementing an electronic pedigree.”

Generic drugs, too

Lutter’s impatience aside, the conference featured evidence that the pharmaceutical industry is not exactly mired in RFID mud. Even generic drug manufacturers, who have been lagging behind on RFID for the most part, are expanding their implementations.

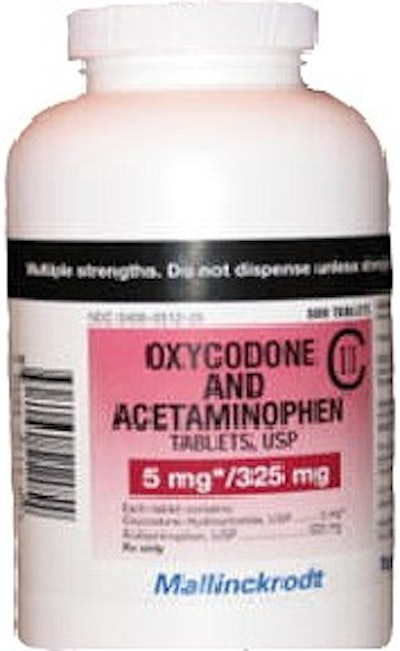

Darrell Biggs, a senior engineer and RFID deployment leader for Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, explained that his company would start tagging bottles and cartons of schedule II controlled substance generics on a packaging line in a manufacturing facility starting in the second quarter of 2006. Mallinckrodt has been manually tagging generics destined for Wal-Mart in one of its distribution centers.

When asked how many drugs would be tagged, Mark Pilkington, special projects lead at Mallinckrodt, said, “Less than all, more than one.”

Biggs explained that it was relatively inexpensive to adapt the company’s existing packaging line for application of Gen 2 RFID tags. He said it cost “less than half a million dollars to upgrade the line,” which fills 120 bottles/minute. But he noted that the cost of upgrading a packaging line “depends on what you do.”

Biggs also noted that while some of the packaging line testing has been done, full validation is yet to happen. Some problems he thought might crop up have not. For example, he was initially concerned about electrostatic discharge interfering with label reads. That has not been a problem.

Viagra RFID more costly

Pfizer’s Staver also discussed costs. She estimated her company would spend between $4.5 million-$5 million in the first year tagging Viagra. That included upgrading the French packaging line and the cost of supplies, including tags, which one industry participant estimated are costing Pfizer 55¢/tag. Pfizer, like Mallinckrodt, will be writing and reading to the bottle tag on-line. In addition, Pfizer will be printing a two-dimensional bar code on each bottle, and an EPC logo. The bar code and RFID tag will use the same EPC number.

Staver explained Pfizer was putting the EPC logo on the bottle, along with language noting the bottle’s carrying of a radio-frequency device, so no one could accuse Pfizer “of spying on consumers.” It did that even though she says an infinitesimal percentage of the 30/100-count bottles will end up in the hands of consumers. Nearly all patients will receive their doses repacked in pharmacy containers.

European requirements

However, as many companies expressed reservations about RFID as those who announced momentum. Mark Seitz, supply chain consultant, global logistics, Eli Lilly and Co., pointed to significant roadblocks to using RFID, such as evolving requirements for “mass serialization” in Europe.

Italy, for example, requires pharmaceutical manufacturers to put what are called “Bollinis,” government distributed labels, on all its drug packages, says Seitz. A French proposal would require a manufacturer to put a "vignette" sticker on the package. “We have a number of product coding options besides using RFID tags to meet these serialization requirements,” explained Seitz. “We can use a one-dimensional bar code, a two-dimensional bar code or even use human readable codes.”

As far as making a decision on which route to go, Seitz stated that Lilly is still evaluating all serialization alternatives and needs to prepare itself for the distinct possibility of a “mixed operational environment.”

Read challenges

Jim Dowden, director of distribution services for Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc., talked about his company’s pilot, which involved tagging vials, blister packs and bottles inside a laboratory that was designed by Cap Gemini in Cambridge, MA. He said it is easy to put a tag on an item, and easy to put a tag on a carton. “But it is not so easy to read that tagged item in that tagged carton,” he added.

That was especially true with blister packs. Hoffman experimented with three blister packs across and three up—for a total of nine—in every carton. Read rates were not very good, he reported.

Read rates were also an issue for H.D. Smith Wholesale Drug Co., one of the nation’s biggest wholesalers. It began a pilot in March 2004 that involved shipping tagged Schedule II controlled substances to five accounts, four of them retail pharmacies and one hospital pharmacy.

Totes tilted for better reads

Robert Kashmer, vice president of Smith, acknowledged there are problems getting readers at those five locations to read the tags on the drugs when they arrive in the totes H.D. Smith uses to ship the individual bottles for an order. Kashmer explained that someone at the reading station has to tilt the tote until he or she gets the best orientation of the tags on the bottles in the tote leading to the highest read rates.

Another company presenter, who later pleaded for anonymity, boldly promised to buy everyone in the room a beer when the conference took place next year if his company had not gotten an RFID pilot off the ground by then. Just before the following session got underway, one attendee leaned over to the person next to him and said in a snigger loud enough to be heard six seats away, “I guess I know I’ll be getting one free beer next year.”