Companies tend to shift priorities between new-product development and cost saving, depending on prevailing winds in the marketplace. Currently, the focus has shifted to cost savings because of the slowing economy and higher raw material prices. Everyone is looking for the lowest cost without diminishing the quality of their product.

I work in the contract-engineering services industry, and it offers a unique vantage point to observe how dozens of companies execute projects, including those in packaging. Seeing both the successes and struggles, it quickly becomes apparent which approaches work and which ones fail. From the engineering services vantage point, the results of projects seem to fall into two categories, both of which have a strong undesirable component:

• Low-cost development but an expensive product

• A high level of initial investment and lower long-term cost.

The one near-certainty about low-cost development is that it usually leaves money on the table. This outcome results from strategies that focus too much on spending as little as possible during development. At a time when cost savings is king, two questions are: “Why was that money left on the table to begin with? Why not get that money on day one?”

Cost savings vs. cost avoidance

The answer to both questions is that reward systems usually value cost savings over cost avoidance. Cost avoidance requires a culture change. Most organizations reward two behaviors—getting the product to market and saving costs throughout the product’s life cycle.

One reason cost savings is the dominant model is that savings are measured easily. Cost savings has a documented before-and-after invoice. If you improve the development process, it is difficult to measure cost avoidance because there was no hard-documented “before.”

In fact, it can be a significant challenge to reduce costs on a project that was optimized from day one. You could argue that if the project were optimized from the beginning, the only true way to achieve cost savings would be a change in the product requirements (lower product expectations), a change in the technology, or a reduction in suppliers’ gross margins.

What is the appropriate amount of effort to expend in a packaging project? The answer is to invest enough effort to discover what you do not know, but need to know, to successfully launch a good packaged product at the lowest possible cost. Why? Failures in the marketplace result from events that were either unknown or misunderstood during product-package development.

For every project there are four levels of awareness. They are as follows:

1. Unconsciously incompetent—you don’t know what you don’t know.

2. Consciously incompetent—you know you don’t know something.

3. Consciously competent—you can perform a skill, but it requires focus.

4. Unconsciously competent—you can perform a task without conscious effort.

A responsible organization easily can handle the last three items on this list. The deadly item is the first one—unconscious incompetence. Companies that work hard to manage it have a better chance of launching a product and keeping costs down. There are many ways to discover what you do not know, provided you are aware that potential pitfalls exist outside your knowledge base.

In nine out of 10 technical failures, the issue is that something caused a failure outside the design requirements. What that means is engineers do a great job designing for product-use conditions that are apparent to them. It is the conditions they do not design for that result in the failure.

Two examples illustrate the point:

• A contract packager designs a package to work in all the reasonably understood consumer conditions. In addition, the company considers factors such as the impact on packages from shaking during product transport. The company begins with production tooling and starts to send the product into distribution. Almost immediately, a big-box retailer complains about packages leaking before they arrive at the store. Some packages were shattered. At this point, the customer is in “firefighting mode” and needs to resolve this issue immediately. The first step is to establish why the packages leak. After examining failed packages, the packer hypothesizes that the failure is resulting from impact or dropping of the bottle.

As part of the initial design, product-drop tests were conducted from a consumer’s countertop. The problem was that when the packages landed on the ground during testing, the impact caused them to leak. After further investigation and 100% inspection, it was learned that the packages were not leaking when they arrived at the retailer’s distribution center (DC), but they were leaking after they left the DC. This meant the failure occurred inside the DC. Some unexpected harsh handling of the product caused the failure.

The bottle is made in a blow-molding process, so the next step was to implement a quick fix by adding material to the bottle. This decision added cost to the product, and it was the focus of a cost-savings project later.

Unstable bottles

Another situation in which the unknown caused a problem occurred on a package-manufacturing line where bottles were conveyed through a filling system. The bottles were optimized to meet consumer needs and to satisfy cost and filling requirements. The challenge was that the bottles were inherently unstable in the conveying system and would tip over on the conveyor, potentially jamming the line.

Often, development staff members make assumptions about automation equipment because they have little experience with using it. In this example, the manufacturing line speed had to be reduced early in the project, when customer demand was greatest. Opportunities were lost to get product out the door. Short-term costs that were added could have been avoided by more thoroughly evaluating package conveyance during the project’s design phase. Again, this project turned into a cost-savings effort.

These two examples are the norm rather than the exception. Usually, project overruns become cost-savings projects when the company culture rewards the person who gets money back. But they never retrieve all the money; some revenues are lost forever.

Companies focus either on cost savings or new-product development, and contract packagers have many opportunities to help their customers’ bottom line.

True cost savings comes from changes in specifications or technology, or from reduced margins. For most projects, the only option in the contract packager’s control is changes in technology.

Technologies and options available to the contract packer include:

• Exploring case-less packaging. There are two key drivers for case-less packaging; sustainability and cost savings. Unfortunately, the decades of knowledge surrounding the performance of corrugate cases is out the window, and the packaging industry is back to square one. Most companies do not have sufficient internal knowledge regarding the construction of case-less unit loads that can survive the rigors of distribution and warehousing. Because case-less technology is relatively new, most organizations don’t know what they don’t know. The solution to this problem is to find the most knowledgeable people on case-less unit load construction and get them onboard as fast as possible.

• Looking beyond your supplier’s typical capabilities. Establish good relationships between suppliers and customers. Once trust is established, information can flow freely between the parties. One important characteristic of a good relationship is a willingness to acknowledge where to draw the line on capabilities. There are two options at this point; the parties work together to develop the capabilities, or you look at other potential suppliers that are a better match with your company.

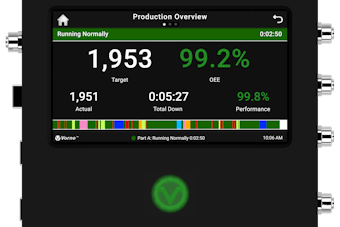

• Using predictive analysis to optimize operations. Unit operations often are optimized “on the fly” when equipment is delivered to a factory. Typically, several operations are being optimized simultaneously. There is some initial debugging at the equipment supplier, but the system is not completely optimized. So when the equipment arrives and is assembled, the system needs to be optimized, and the highest priorities are tackled first. Low-priority issues are solved after product launch.

There are two issues with this approach. First, machine builders might not be the best source for optimizing their own equipment. They try to understand upstream and downstream processes, but only enough to build their equipment. Second, the equipment might have design flaws and be incapable of delivering stated productivity levels.

Use technology to do predictive work on unit operations, including interactions between unit operations prior to designing and building the equipment. This approach will allow for early system optimization.

When it comes to new-product development or cost savings, look for what you don’t know. This is where opportunities exist to avoid costs and save money.