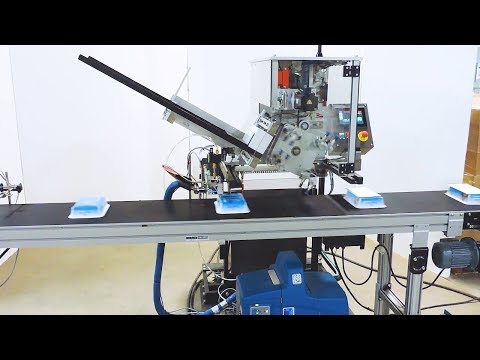

Coca-Cola's shaped can may have set the standard for proprietary packaging. But a couple of ex-beer truck drivers from Long Island may have done Coke one better. Arizona Beverages has just released a version of its ready-to-drink iced tea in what it calls a "Sport Can." Only it's not a can. It's an extrusion/blow-molded multilayer polypropylene container from Owens-Brockway (Toledo, Ohio). Shaped to look like Arizona Beverage's regular 24-oz double-height aluminum can, this container has a convenience feature the aluminum can doesn't: molded finger grips along the back. And unlike aluminum, the package is also soft and squeezable, patterned after the squeeze bottle often held by clips on a bicycle. "I wanted something that squeezes well, something that conforms to your hand," Don Vultaggio tells Packaging World. Vultaggio, along with his partner John Ferolito, owns and operates Ferolito, Vultaggio & Sons in Lake Success, Long Island, NY, which manufactures and markets the product. From humble origins as a local New York beer distributorship, the company has made beverage industry history with its arresting package designs. Vultaggio created this package, as he does just about all of those marketed by the company. Arizona Beverages prides itself on its graphics. The Southwestern motif sports vibrant colors, and when coupled with an intriguing textured "pigskin" background, it creates a three-dimensional quality. Copy on the pigskin reads, "Official Sport Can." The graphics are courtesy of a 2-mil polyvinyl chloride full-body shrink sleeve label gravure-printed in nine colors by American Fuji Seal (Bardstown, KY). Topping off the package is an extra-wide 43-mm push-pull sport closure from Creative Packaging (Buffalo Grove, IL). FV&S selected this closure for its high flow characteristics. 'Look ma, no panels' The package is a true milestone for several technical and functional achievements. At the top of the list is the fact that it's a soft, squeezable, straight-walled container that resists collapsing, also known as paneling, after cooling from its initial 175°F hot fill. How is this done? For its part, Owens-Brockway officials say the container structure-PP/plant regrind/adhesive/ethylene vinyl alcohol/adhesive/PP-is its standard ketchup bottle barrier material. That's why the bottom of the container is coded with the Society of the Plastics Industry's "7" for "other." Aside from providing a better oxygen barrier than polyethylene terephthalate and a one-year shelf life, O-B admits the trick is not so much in the molding as it is in the filling. For more details, we have to travel north, across Lake Ontario into Canada, to visit the suburban Toronto plant where the product is contract-packaged by New Wave Beverage (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Deliberate overfilling To prevent paneling after cooling, great pains are taken to virtually eliminate all headspace in the package. With almost 100% of the volume occupied by liquid, there is almost no air left to compress as it cools, which would otherwise bring the container to its knees. How do they do it? The answer, as it turns out, borders on packaging blasphemy. "It's a 24-ounce container, and we have to put 25 ounces of product in it," says Rick Page, vp of operations at New Wave. This results in 1 to 1.5 mL of lost product per container due to spillage. It's simply factored in as a cost of producing this package. The other part of the equation is a specially shaped inner seal that sinks down into the container to eliminate any remaining headspace. And the inner seal-uncommon on most beverage products-is absolutely necessary for this hot-fill product, since an air-tight barrier is critical to keeping out oxygen. Vultaggio says these steps are required with a PP container. And only PP would meet the squeezability requirement, despite the fact that heat-set PET-typically used for hot-fill applications-would have cost less than the multi-layer container now in use. Inner seal ins and outs Although the package was ready to be launched early this year (it was first shown publicly a year ago at InterBev96 in Houston, TX), it's only now being produced on a commercial scale, with national distribution expected to be completed by the end of the year. The reason for the delay turned out to be a leaker problem. Difficulties in getting the seal to mate with the soft-ended PP container during capping required an alternative method of sealing. The solution involved a somewhat radical approach for beverage packing: Apply the inner seal by itself separately after filling. Capping isn't executed until after the container has traveled through the cooling tunnel. Inner seals are applied and sealed on what's called a pressure-belt induction sealer from Stanpac (Smithville, Ontario, Canada). Stanpac integrated a pick-and-place applicator from Minnesota Automation (Crosby, MN) with a specially modified induction sealer from Enercon (Menomonee Falls, WI). After inner seals are placed onto containers, containers are captured from above by a moving belt. The belt holds the inner seals in place while they pass through an electromagnetic field created by the Enercon unit's coil. That induction sealer has a specially modified coil to accommodate the belt. The constant belt pressure on the inner seals results in strong, positive seals. The inner seals themselves, also supplied by Stanpac, are quite unique. Unlike traditional flat discs, these are actually pre-formed into a specific shape. The seal membrane dips down into the center and rises up to conform to the the extra-broad land surface of the container rim, which O-B increased to 0.090" from the original 0.030" thickness. The inner seal also has a slight downward overhang outside the bottle finish, which helps keep it centered on the container before it reaches the belt. Consumers can grip the overhang to remove the seal before consuming the product. This inner seal performs like a closure itself. Stanpac has used a variant of the technology for applications involving formed closures for glass milk bottles and single-serve juice beverages. Stanpac says that there's nothing inherently special about the foam/foil/plastic lamination itself, though it is thicker than what New Wave initially used when it tried traditional in-line capping/induction sealing. Rick Page admits that the separate application is more expensive than traditional in-line capping with the seal already in place in the closure. But it's paid off: The leaker rate has dropped to a low tenth of one percent, he reports. Some equipment added Several new pieces of equipment were added to New Wave's packaging line in order to run the Sport Can. (The line also runs 16- and 20-oz glass bottles of Arizona beverages.) Apart from the seal applicator, the line has a custom-designed on-line leak detector built by New Wave's sister company Alimpo Machinery (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), a machinery rebuilder. Also new for this line is an Intersleeve shrink sleeve applicator (also through American Fuji Seal), which constitutes the first North American installation of the equipment in an actual bottling plant (see sidebar, p. 30). The line starts out as containers proceed through uncasing and rinsing. Filling is done by an existing rotary pressure filler, calibrated to fill product up to and beyond the rim of the container. "It's very important that this container is filled right to the brim," says Page. "When the fill level is below the first thread, the container will panel when it cools down." Next comes the inner seal application. Containers are captured by timing screws that pace containers as they pass through the pressure-belt sealer. First, a rotary pick-and-place mechanism with three suction cups plucks pre-cut inner seals from a magazine and drops them on top of the incoming containers. Dual magazines allow the seals to be replenished without stopping the machine. Once the seal has been placed, the container is conveyed about 4" until it passes beneath the rubber pressure belt. The belt, about 4' long and timed to the conveyor, is positioned just high enough to allow the containers to pass underneath. The belt keeps about 4 to 7 psi of pressure-which varies, of course, depending on the slight height variations of each container-on the tops of the containers. Meanwhile the Enercon unit directs an electromagnetic field at the seal area. That causes the aluminum to heat up, melting the bottom plastic layer and bonding it to the land surface of the container. Stanpac built the machine by combining several original components with the Minnesota Automation pick-and-place unit and Enercon induction sealer. New Wave Beverage modified the machine, adding a heavier-duty belt and a device that meters liquid nitrogen onto the belt to keep it cool to counter the heat build-up from the aluminum inner seals. Putting on the squeeze After induction sealing, the containers enter a cooling tunnel where water jets spray the containers to cool the container surface down to about 95°F. Containers are then blow-dried and shrink-sleeve labeled (see sidebar). Finally, just prior to capping, the container is tested for seal integrity with a unit that New Wave built itself. It plans to patent the machine as a low-cost seal integrity tester through its Alimpo division. Essentially it's a standard cap retorquer that's been reconfigured to squeeze each container's sidewalls with 7 psi of pressure in an attempt to break the seal. "It's just an ordinary retorquer with six spindles on it," explains Page. "Each time it squeezes through these rollers, the seal pops up a bit." If the seal blows, a photocell inside the machine picks up the movement, signalling an arm to reject the offending container off the line. "We feel that seven psi is more than ample to double-check the seal. We tried three, five and six. Seven picks up pinhole leaks and that was our main concern," says Page. The tester is strategically positioned near the end of the packaging line, after cooling and after the shrink label heat tunnel. That application of heat has the potential for weakening the inner seal, according to Page. An expensive package FV&S admits this is an expensive package. "We pay somewhere around a 40 percent premium [for contract packaging fees] and about a 50 percent premium on the package materials themselves," says John Balboni, executive vp of business development. That's compared to the company's standard 24-oz aluminum can. But, Balboni points out, the Sport Can commands a high retail price, $1.25 to $1.50 for 24 oz of product. In comparison, "Coke's selling two liters-67 ounces-for 99 cents." The higher price translates into "substantially higher margins for us and our distributors," according to Balboni. "My beverages sell at premium price," concludes Don Vultaggio. "When you're at this level, you can put some of these bells and whistles on the package that the other guys can't."