As counterfeiters around the world grow increasingly sophisticated, some experts now estimate that about 8% of global commerce is counterfeit. Equally troubling to some brand owners is the problem of diversion, where products meant for specific and carefully targeted regions or channels of distribution wind up being diverted to very different regions or channels.

Fake pharmaceutical products are especially worrisome. In June the European Commission released data showing a fivefold increase in counterfeit medicines over 2006. The good news is that the EU and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative—an arm of the executive branch responsible for the nation’s international trade policy—announced plans Oct. 23 for the Anti Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA). A global pact involving major trading partners—including not only the U.S. and Europe but also Japan, Korea, Mexico, and New Zealand—the agreement is significant partly because a key platform revolves around the issue of better law enforcement policies and the creation of a legal framework that recognizes how serious a scourge counterfeiting has become in the 21st Century.

Brand owners aren’t waiting, however, for these global mechanisms to emerge. In multiple product categories around the world, brand-protection strategies aimed at fighting both counterfeiting and diversion are being implemented, and packaging is front and center in these initiatives.

A perfect example is seen at Jemella, the marketer of a high-end line of hair-styling irons that retail for just under $300. A relatively young company based in Yorkshire, England, Jemella operates under the trading name ghd. It now sells about 1.5 million of its styling irons annually. The firm began seeing knockoffs in counterfeit packaging within two years of its 2001 launch. So it began working in close cooperation with Schreiner ProSecure on authentication and track-and-trace solutions. The KeySecure tracing system, for example, is a label with special, three-dimensional, true-color holograms incorporating a 15-digit alphanumeric authentication code enabling online, Web-based authenticity verification. Customers, dealers, and Jemella employees are all able to verify product authenticity as needed because the label with the KeySecure code is affixed to the power cord of the styling iron itself.

The KeySecure code is encrypted and protected by a multistage firewall system, and the codes can neither be duplicated nor copied by random generation, says Schreiner. Codes are generated by a high-security computer system combining various encryption technologies. Each label is printed with a unique code issued in compliance with stringent security controls. After products are shipped, the respective code batches are activated for verification via the Schreiner query system. This is done using a secure link on Jemella’s Web-site.

A second component of the KeySecure system involves a label applied to the corrugated secondary packaging that holds 20 boxed styling irons. The bar code on this thermal-transfer-printed label links the corrugated secondary packaging with the 20 unique codes on the power cords inside. This parent/child relationship gives Jemella added track-and-trace visibility into the entire supply chain.

To complement this KeySecure solution, Schreiner has developed a special software and bar-code labeling system. Each product or batch is scanned before shipment and is linked with the data of Jemella’s trading partners across the distribution chain for reliable tracking of product flow in a way that discourages diversion.

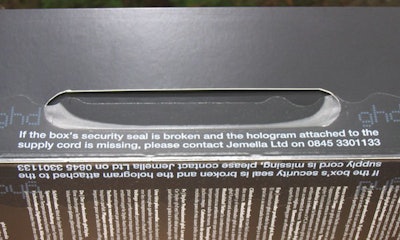

An additional layer of security in place—one that’s more conventional than encrypted codes but still mighty effective—is a Schreiner security seal applied manually to each individual box. Material specs are considered proprietary, but the seal’s essential function is that of a tamper-evident seal. Copy printed on the seal reads “If the box’s security seal is broken and the hologram attached to the supply cord is missing, please contact Jemella Ltd on 0845 3301133.”

Much of the responsibility for brand protection at Jemella is shouldered by Paul Overend. He believes that a constantly changing assortment of brand-protection solutions is an absolute necessity.

“We believe in escalating steps,” says Overend. “When one set of security measures is breached, we have the next one ready. So we build security measures in advance of when we actually need them. Schreiner has been helpful in this process. Essentially they are a label converter, but they’ve been able to incorporate security components at a very high level.”

The brand-protection measures Jemella has implemented haven’t come cheaply. Overend figures he now pays five times as much for packaging as he did in 2003. He also believes a logical next step will be to further bolster his security efforts by adding personnel whose key responsibility will be brand protection—whether it’s working with packaging technology providers, customs agents, government bodies, or whatever. Such is the cost of doing business, he reckons, in today’s marketplace.

Bumble and Bumble

Operating at very different price points than Jemella are the Esteé Lauder division known as Bumble and Bumble and the marketer of haircare products and other health and beauty aids known as Paul Mitchell. While they are certainly not immune to the counterfeiting of their products, it’s diversion that is public enemy number one. Their brands are all about cache, which is why they are only supposed to appear in salons and other high-end outlets. If unscrupulous distributors divert them to everyday outlets like Walgreens or CVS, these brand owners can kiss cache—and their brands—goodbye. Each firm is taking a different route to tackling the problem of diversion.

At Bumble and Bumble, the IMprints Track & Trace Solution Suite from Videojet is being used. A high-level description of this implementation was provided at a Videojet press conference at Pack Expo Las Vegas. Videojet also used the press briefing to announce the recent formation of its Brand Protection Unit.

At Bumble and Bumble, a Unique Identification (UID) code is generated by IMprints CodeMaster, a software program residing on a computer. This UID is sent to an ink-jet or laser printer, which applies the UID as an alphanumeric code to the bottle. As the bottles proceed to case packing, a machine vision system records which UIDs are in each case. A case code linking those bottles to that case is generated and printed on the case, thus establishing a parent/child relationship between the case and every bottle in the case.

As cases move toward palletizing, another machine vision system—in the press conference presentation, both machine vision systems appeared to be from Cognex—records which cases are on which pallet. A pallet label bearing a code linking those cases to that pallet is generated and applied to the pallet. So when the pallet leaves the plant, there are codes in place to track which pallet holds which uniquely coded cases and which cases hold which uniquely coded bottles.

At this point, the pallets go to one of three distribution centers. At each DC, case codes are scanned as cases are assigned for shipment to individual salons, so there’s a clear record of which cases went to which salons. If a Bumble and Bumble product is found at an unauthorized retail outlet, the UID on the bottle can be entered into IMprints Track It!, a Web-based service that spells out the complete history of where that bottle was prior to its appearance on the shelf of the unauthorized retailer. By combining this information with data from their other business systems, Bumble and Bumble is able to identify where diversion took place and who is responsible. Armed with this track-and-trace capability, the firm can take corrective action.

Paul Mitchell

A different approach is being pursued at Paul Mitchell, where containers are supposed to go from manufacturing to distribution center to distributors to salon. When product reaches the salon, stylists use it or salon patrons buy it. What’s not supposed to happen is for product to show up in mainstream retail outlets. But unfortunately, it does. So the firm has had to figure out an anti-diversion strategy.

“In the past, our feeling was that the combination of codes on containers and the legal system in place should be enough to address the problem,” says Paul Mitchell president Luke Jacobellis. “And this has proven true whenever counterfeiting has surfaced. But diversion is different than counterfeiting. The prevailing attitude about diversion is that the right of free trade is so fundamental, that if I sell you a product, you can resell it. Should we choose to pursue enforcement, it’s a civil matter, which is cumbersome and expensive. So the strategy we’ve emphasized in the past few years is to gain tighter control over our own trade.

“We looked at our distribution channel anew. If we found containers in outlets where they didn’t belong, the code on the bottle told us who the distributor was. So we told that distributor to control the leak in his channel. That didn’t really work, so we decided to solve the problem by controlling our product while it was still in our distribution system. Once it’s out of the barn, it’s pretty hard to corral it back in. So we built a better barn.”

The foundation of this “better barn” was what Jacobellis describes as “good, strong, direct communication with distributors and corrective action where needed.” It appears to be working, as diversion is down roughly 44% since the new strategy was implemented. Needless to say, fewer distributors are in the picture. “I used to have 10 distributors in the region stretching from Mexico through Central America and down into South America,” says Jacobellis. “Now I have one in Mexico and one in Brazil.”

Unique authentication marker

High-end wine is another product category that counterfeiters find attractive. That’s why Colgin Cellars, whose Napa Valley wines routinely fetch hundreds of dollars per bottle, has adopted a brand-protection solution from Kodak. Kodak Security Solutions is a suite of products and services built on Kodak’s sizeable intellectual property portfolio and on its digital imaging, document imaging, and graphic communications. Among the more sophisticated offerings in the Security Solutions portfolio is Kodak’s Traceless system. It uses invisible markers that can be added to inks, papers, or other packaging elements. These markers are detectable only with proprietary hand-held readers that indicate whether a product is real or fake.

Detailed information about the application is not available from Colgin Cellars. But owner Ann Colgin has this to say about protecting her super-premium brand:

“While Colgin Cellars has not experienced any problems with counterfeit wine, the issue has concerned me for some time. I felt it was necessary to take a stand and ensure my customers a guarantee of authenticity. Kodak worked closely with me to quickly develop and implement a solution that met my demanding production schedule. Within 45 days, Kodak evaluated solution options, conducted a pilot test, delivered a proposal, and implemented a solution that protects Colgin Cellars products.”

Vineyard 29 in St. Helena, CA, will soon be another user of Kodak’s authentication technologies. Owner Chuck McMinn, like Colgin, prefers not to say where Kodak’s technology resides in his screen-printed bottles. But he thinks the use of this technology will soon spread.

“It’s not a matter of having every bottle go past a Kodak reader as it moves through the supply chain,” says McMinn. “Rather, if a question arises or a problem surfaces, we can get a reader into position and concretely address the problem.” Just knowing that the possibility for definitive authentication exists is half the appeal, says McMinn.

Expect to see more implementations of such brand-protection technologies in the wine sector in the near future.

Kodak’s Security Solutions will also get the nod at Med Health Pharma LLC, a new drug repackager that is building a new plant in North Las Vegas, NV. The firm is focused on Point-of-Care Dispensing. In other words, it won’t package drugs that make their way to pharmacies. Its focus will be on packaging drugs for doctors’ offices, so that when a doctor’s diagnosis includes medication, the patient can receive the prescription right at the doc’s office without a separate trip to the pharmacy.

One other aspect of the Med Health business model is important to point out: Distribution will not be handled by the three large distributors through which most pharmaceuticals flow in the U.S. Bottles will be sent instead to Med Health’s own distribution centers in trays. From there, the trays will go to a pharmaceutical wholesaler allied with Med Health. That wholesaler will take the package to the doctors’ offices. Moreover, the only drugs the firm will handle will be the 10 or so most commonly prescribed drugs.

According to Sam Haddad, vice president of operations at Med Health, each high-density polyethylene bottle, holding anywhere from 10 to 30 doses, will include a Kodak security feature.Two other promising new security packaging technologies will be deployed, one from Yottamark, the other from SupplyScape.

“The YottaMark system gives us a 2D bar code that identifies date and lot, expiration date, product ID, and a unique serial number that gives us traceability right down to the individual bottle,” says Haddad. “It puts the distribution center and the physician in a position to detect against counterfeiters. It allows tracking down to the bottle level because each bottle has a unique ID. Moreover, we at Med Health know how many times a bottle gets scanned. If it’s only supposed to get scanned by the DC and the physician, and I see it’s been scanned more often than that, I can flag it in case a doctor somewhere sells that brand to someone else. We see the container’s entire history.”

The security component from SupplyScape is called the On-Demand Value Network Product Security Solution. It delivers a track-and-trace infrastructure that includes electronic pedigree, product authentication, and partner integrity capabilities. This solution, says SupplyScape, spans the entire pharmaceutical supply chain, from manufacturer through distributors and 3PLs (third-party logistics firms) to dispensation to the patient.

DNA applications

The use of DNA as a brand-protection tool is getting talked about with increasing frequency. From Taiwan comes an especially intriguing application involving what might be the world’s most expensive tea. Grown in limited quantities in a remote part of Taiwan, a pound of Alishan High Mountain tea can sell for as little as $300 or for as much as $6,500. Little wonder that counterfeit activity has sprung up around it.

What the brand owner needed in this case was a way of giving consumers confidence that they were getting the genuine article and not a counterfeit product. The company opted for DNA encryption from Applied DNA Sciences.

The tea comes in a fiber-wound paper canister with two canisters per folding carton. In the carton are two film-wrapped swabs that the consumer opens and uses to swab a spot label on the front of the brightly decorated canister. If the DNA mark on the label goes from blue to pink, the contents of the canister are authentic.

At the foundation of this DNA-based security solution is the age-old practice of encryption: converting data into a form that can’t be understood by unauthorized people. In this case, the data that gets converted is plant DNA. Applied DNA Science extracts it from a plant and then scrambles its information content. This reassembled plant DNA becomes a marker. The marker is then encapsulated and stabilized so that it can be embedded directly on a product, on a package, or on fibers. In the case of Alishan High Mountain tea, it’s embedded in a color-changing ink. The ink is sent to a label converter who uses it in the printing of a spot label. Once the label is applied to the fiber-wound canister of tea, the package now carries a unique and virtually impossible-to-duplicate DNA marker. The remaining piece of the puzzle is the swab. It contains a proprietary solution that reacts with the authentic DNA marker and causes the color-changing ink to go from blue to pink. No DNA marker, no color change.

What’s next?

So what should we expect to see in the way of brand-protection packaging in the near future? One opinion comes from Lynn Crutchfield, president of Acucote Inc. and president of the 13-member Brand Protection Alliance.

“The onslaught of new, emerging technologies is slowing as we learn to work with and implement authentication technologies on a broader scale,” said Crutchfield at October’s Product Authentication & Brand Security (PABS) conference in Washington. When it comes to brand-security programs, “brand owners’ needs are greater today than ever before,” he added. Meeting those needs will become a major priority at packaged goods companies in the very near future.