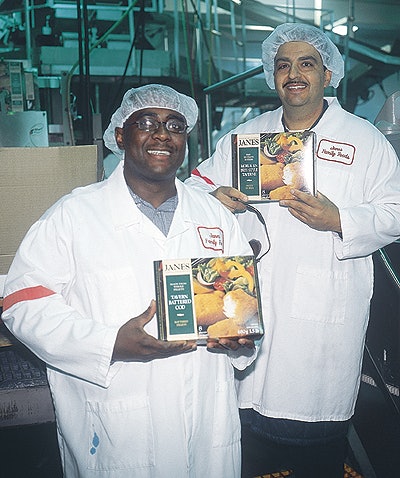

Janes Family Foods is saving upwards of $1 million a year in labor and material costs, thanks to carton-forming and carton-closing/sealing machines used at two of its plants.

A carton erector and a carton sealer recently added at Janes Family Foods’ individually quick frozen (IQF) chicken processing and packaging plant in North York, Ontario, Canada, helped double production and trim labor costs by half. That success led to the firm’s 2001 purchase of two more HS 2/60 double-head lock carton formers and two Compact 3 sealers at its Concord, Ontario, Canada, headquarters plant, which produces IQF chicken, seafood, and vegetables. All six machines were manufactured by Bradman-Lake (Charlotte, NC).

In the United States, these frozen foods are typically sold in plastic bags and merchandised in stand-up freezers. But in Canada, these products are usually marketed in deep chest freezers, where an outer carton better withstands stacking than just a bag.

The primary difference in the equipment used at the two plants is the configuration of the closing machinery. The higher-volume North York plant uses an in-line configuration to achieve higher speeds, while Concord’s two Compact 3 sealers are set up on right angles to save space in that facility’s cramped packaging area.

“Before we bought the equipment we were setting up preglued cartons by hand at our plant,” says Leonard Cole, North York’s plant manager. “That took a considerable number of people. We had operators put a plastic bag of frozen chicken pieces into each carton. Then they would close the box, which would be shrink wrapped or manually sealed with tape.” He says, “We used six people to do those tasks. Now we need just three, so there’s a significant reduction in labor costs.” Downstream, the new carton sealer requires only one operator; it took two to three people with previous semi-automatic closing equipment.

Cole says that with the new equipment, the company is saving more than $1 million per year in labor costs. The overall savings for Concord’s two lines are higher than at North York, but the per-machine savings are greater at North York because of larger volumes. Cole points out that as Janes’ business continues to grow, higher volumes at both plants would have necessitated additional workers to keep pace.

Automating carton forming and sealing not only lowers labor costs, it also reduces the “potential for workmen’s compensation claims, and the repetitive-motion injuries [possible with] opening and forming boxes,” adds Cole.

Carton changes

Material savings provide another significant financial benefit for Janes. During Packaging World’s plant visit, Cole explained the company previously used a “Beers”-style paperboard folding carton manufactured with glued corners and scored diagonally on the sidewall so that the carton sides could be folded down and shipped flat to help save storage space.

“It was a one-piece carton with a cover that folded over,” Cole notes. “We would receive them in bundles of 50. We’d have to open them, ‘puff’ up each one, put in the bag of product, close the top of the carton over, tape the carton closed, then shrink wrap the box. Besides being labor intensive, the boxes were expensive.”

By adding the automated cartoning equipment, Janes switched from cartons that had to be sealed shut with hot melt to folding cartons with locking tabs from Boehmer Box (Kitchener, Ontario, Canada). The 28-pt cartons are wax-coated on both sides to provide moisture protection. Cartons are printed offset in six or seven colors.

“With the Beers-style cartons, we used 17 different ‘die lines,’” or carton sizes, says Cathy Noel-Gonsalves, Janes’ procurement specialist for packaging and ingredients. “We sourced them from two different suppliers. Now,” she continues, “we use 11 varieties from a single supplier. And because we order fewer carton sizes, we order more of each. That gives us a price advantage due to our volumes.” Fewer carton varieties are needed because this carton style allows them to use the same width and length dimensions, changing only the height to accommodate different product fills.

How that translates into financial savings is difficult to measure, Noel-Gonsalves notes, in part due to increases in board material and board supplier labor costs. She estimates, however, that cost savings range between 6.5% and 25% when similar-sized Beers-style cartons are compared with the current cartons.

The new cartons also save in shipping expenses. Cole explains, “we used to receive between 1길 and 2ꯠ Beers-style cartons on a pallet. [That] was very inefficient compared to our current cartons, which are received 7귔 per pallet. That saves us a considerable amount of space in the plant, and has eliminated our need to rent outside storage space, which is getting rather pricey.”

Cartoning at North York

At Janes’ 50ꯠ-sq’ North York location, the line runs 17¼ hours a day on two daily shifts, for five or six days a week, depending on the season. A third shift performs equipment sanitation procedures. The line produces 6ꯠ to 7ꯠ lb of chicken/hr, in nuggets, strips, or patties. Product is packaged in about 50 different weight varieties from 350 g (12.35 oz) to 2ꯠ g (70.6 oz).

The plant receives boneless chicken, which it cuts, seasons, breads, and “par-fries,” or partially fries, then quick-freezes. (The meat is fully cooked by consumers when they prepare the food.) From processing, the product is conveyed to a vertical form/fill/seal machine that fills it into unprinted low-density polyethylene film. Sealed bags are conveyed to an accumulating table near the discharge side of the HS 2/60 carton former.

The former contains two magazines that hold carton blanks. A blank is extracted from each magazine by a mechanical tool equipped with vacuum. The blank is positioned on top of the forming head tooling before a plow descends, pushing the blank down through the forming head. In the process, the four corners of the carton lock together by a tab that’s pushed through a slot in the corner of the carton’s base. The carton former works at speeds to 120 cartons/min (60 cycles/min), depending on the carton size.

As open cartons are discharged onto the conveyor from the forming machine, operators place filled and sealed bags of chicken into them. Bags continue along a conveyor to the Compact 3 case closer.

Unlike conventional mechanical chain-and-flight closers, the Compact 3 does not require a timed infeed to space cartons into individual flight spacings. Instead, the Compact 3 uses powered side-running rubber “fingers” on the machine’s infeed. These fingers are positioned on an orbiting track so that one finger contacts the front of each carton while another contacts the back. The fingers flex as cartons are conveyed through to create the needed spacing between cartons.

The cartons are conveyed through the infeed section, and the upright top flap contacts a stationary finger-like device. This causes the top flap to descend down around the carton base. At this point, the carton continues on the conveyor, guided by flexible fingers that are part of a separately powered overhead conveyor. As the carton is conveyed, a photoelectric sensor senses its arrival. The sensor sends a signal to a hot melt system from Nordson (Duluth, GA). A glue gun then fires a predetermined length of hot melt along the base of the carton. A stationary bar plows the front of the top flap against the front of the carton base, using compression to create a bond.

Setup differences

Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the carton-closing equipment is that it turns the carton 90° after its top is plowed down and sealed. By turning the carton, the side flaps are positioned in the same direction as the conveyor. That positioning allows the machine’s second “closing leg” to glue down the two side flaps. This process is done much like it was with the top flap, but with hot melt applied from two positions to seal the two side flaps. Cartons are manually packed into shipping cases, which are placed on a pallet, then unitized on an older rotary stretch wrapper.

Cole says, “we were able to increase our pallet efficiency by about 30 percent. When we changed cartons and automated the process, we studied our pallet-stacking patterns and found that there had been some odd shapes that didn’t lay out well. For example, we could fit about 55 of our two-pound boxes on a pallet before and today it’s 60. We went from 55 to 72 on our 680-gram (24-oz) size, and 24 to 40 on a pallet for a larger size pack.” He attributes these gains to a pallet-stacking computer software program from Cape Systems (Dallas, TX).

Pallets are then brought to a freezer at the North York facility, or shipped to a third-party cold storage facility from which grocery store trucks pick up loads.

Although North York employs in-line carton closing, tight spacing at the Concord plant led Janes to setting up its two Compact 3 machines on right angles. Rather than using the machine to turn the carton after its top flap is plowed down, the cartons are conveyed to the end of the first conveyor leg and stop momentarily before a stationary bar pushes them 90° along another conveyor for carton sealing.

“We produce a more diverse product line at this plant,” explains Concord’s plant manager Nick Boragina. “Between the two lines we produce 77 different items packaged in sizes from 454 grams [16 oz] to 1꺞 grams [60 oz]. Some of these go into glued cartons, or for foodservice packages as well,” he notes. Last year, the plant produced 847 items on 273 days on the two lines, so equipment changeover is important.

The ability to change the Bradman-Lake equipment quickly is one reason Janes selected it in the first place. “It was one of our key areas of focus,” says Boragina. “We wanted to make it easier for operators, and be user-friendly.” Hand cranks and easy-to-change settings for different carton sizes permit 15-minute changeovers on both the carton formers and closers at each plant.

Canadians prefer cartons

Cartoning efficiency is especially important for Janes, Cole says, because so many grocery stores in Canada are equipped with chest freezers where products are stacked from the bottom up. “The grocery stores in Canada are set up somewhat differently than in the United States,” Cole says. “We use more of the bunker-style chest freezers, though stores here are slowly changing to the stand-up freezers more common in the United States. So our philosophy is that a bag of frozen products won’t hold up as well as cartoned products in a bunker freezer. We’ve tried it before, but when you have bags on top of bags on top of bags you will have a lot of crushing and product damage. A folding carton holds up better in shipping and in the freezer displays.”

The Concord, Ontario-based family business also prefers the graphics punch cartons provide. “Bags in a freezer tend to get crinkled and the graphics don’t appear as sharp as on a carton where there are more panels available to display your messages,” Cole contends.

Products are sold primarily at retail grocery stores in Canada, though about 20% are sold to institutional accounts. Product is sold under the Janes Family Food name, as well as under private-label brands. Some product, which bears the Coming Home Group brand, is shipped into the United States.

One-year payback

Cole says that Janes Family Foods personnel visit trade shows, Web sites, plants of other companies, and read trade publications to keep abreast of packaging machinery that could benefit the company. When it looked to reduce the labor costs related to setting up Beers-style cartons, Janes considered end-loading and side-loading cartons as well. “But because they wouldn’t accept some of our products, we made a decision early on to go with top-loading versions,” says Cole.

“Then we searched for companies that made top-loading carton equipment and narrowed the choice down to three vendors,” he continues. “We wanted something compact and reliable, and we selected Bradman-Lake. We also felt that we could build a relationship with them, and we have. We’ve been extremely happy with the equipment, and it’s given us about a one-year payback.”

Cole takes particular pride in pointing out that workers were not laid off as a result of the cartoning improvements at the two Janes plants. “At first people were very apprehensive. We had meetings and discussed it with the staff, saying we were adding this equipment and were going to require fewer people. But there was also a need to increase production,” he adds. “So we’ve taken people away from carton setup and closing and moved them to other areas of the plant. We essentially doubled production without having to let anyone go,” Cole states.