Opportunity may be knocking in a big way for companies having difficulty finding skilled employees. U.S. business now has a fresh chance to mold federal job training programs into, if not a work of art, then at least a "workable ark." In many cities and counties, programs will be held in what will be known as the "One Stop" center. Private industry will occupy the majority of board seats for each center. So local companies will be steering the ark, up whose gangway will climb the disadvantaged and disabled, as in the past. However, for the first time, average Joes and Janes who in the past were not eligible for U.S. Department of Labor training programs will also be participating. "I am optimistic these changes are a step in the right direction," says Tom Lindsley, vice president of policy and government relations for the National Alliance of Business, an association of large companies who use the NAB to lobby on human resource and training issues. In the past, fewer than 100 One Stop centers existed around the country. DOL programs such as the Job Training Partnership Act were delivered through "Private Industry Councils." They were generally regional, run by states, and locked into training contracts with community colleges and private companies who were not held accountable. Only the disadvantaged qualified for the DOL training programs, and there were separate requirements states had to meet for numerous "socioeconomic strata" within that population identified as disadvantaged. The result was that local companies avoided the system like it were poison ivy. "In terms of working with public employment service agencies, many of our employers have found that the agencies were not able to refer to them candidates who meet their skill requirements. When companies asked for referrals, they were often not provided on a timely basis. Finally, when graduates of training programs entered a work force, there is often a painful discovery that the individuals have not acquired the skills that employees need to function there," says Daniel Berry, vice president for work force preparation, the Cleveland Growth Assn., which is the nation's largest Chamber of Commerce. One Stop centers and local companies will no longer have to worry about differentiating 163 training and vocational programs. States will get three block grants: for adult education, vocational education and job training. Each local work force investment area, corresponding to the boundaries of a city, county or metropolitan area, will decide how its portion of each of the three streams is spent. No longer will the localities have to spend a certain percentage of DOL money on each of numerous disadvantaged population groups. The Private Industry Councils of the past generally awarded large training contracts to a few providers, who may or may not have been sensitive to the particular economic trends and job needs in distant parts of the state. In the new system, the state will certify a long list of potential job training providers. This list can be expanded or contracted by the local work force development areas under certain conditions. When an individual comes in looking for work, he or she will be assigned a case manager. The case manager will help that person decide the kind of job for which he is best suited. The individual will then be given a "skill grant voucher" that he can take to any of the approved job training vendors. These training providers will have to meet performance standards, set by the state, in categories such as the number of trained workers who stay in jobs for six and 12 months and the wages received at six and 12 months. States will have to maintain data on these measures using existing quarterly wage records available through the unemployment insurance system. Only a few states do this now. The big question mark in all this is whether local companies will roll up their sleeves and become active in the local partnership councils that will run the local work force development areas. "If the One Stop centers are set up right, they will become 'the place where all the action is' on local economic development," says Lindsley.

Congress revamps job training

States are planning to designate 'one stop' training centers run by local, private industry. And they won't only serve the disadvantaged as in the past. Average workers can be trained, too.

Sep 30, 1998

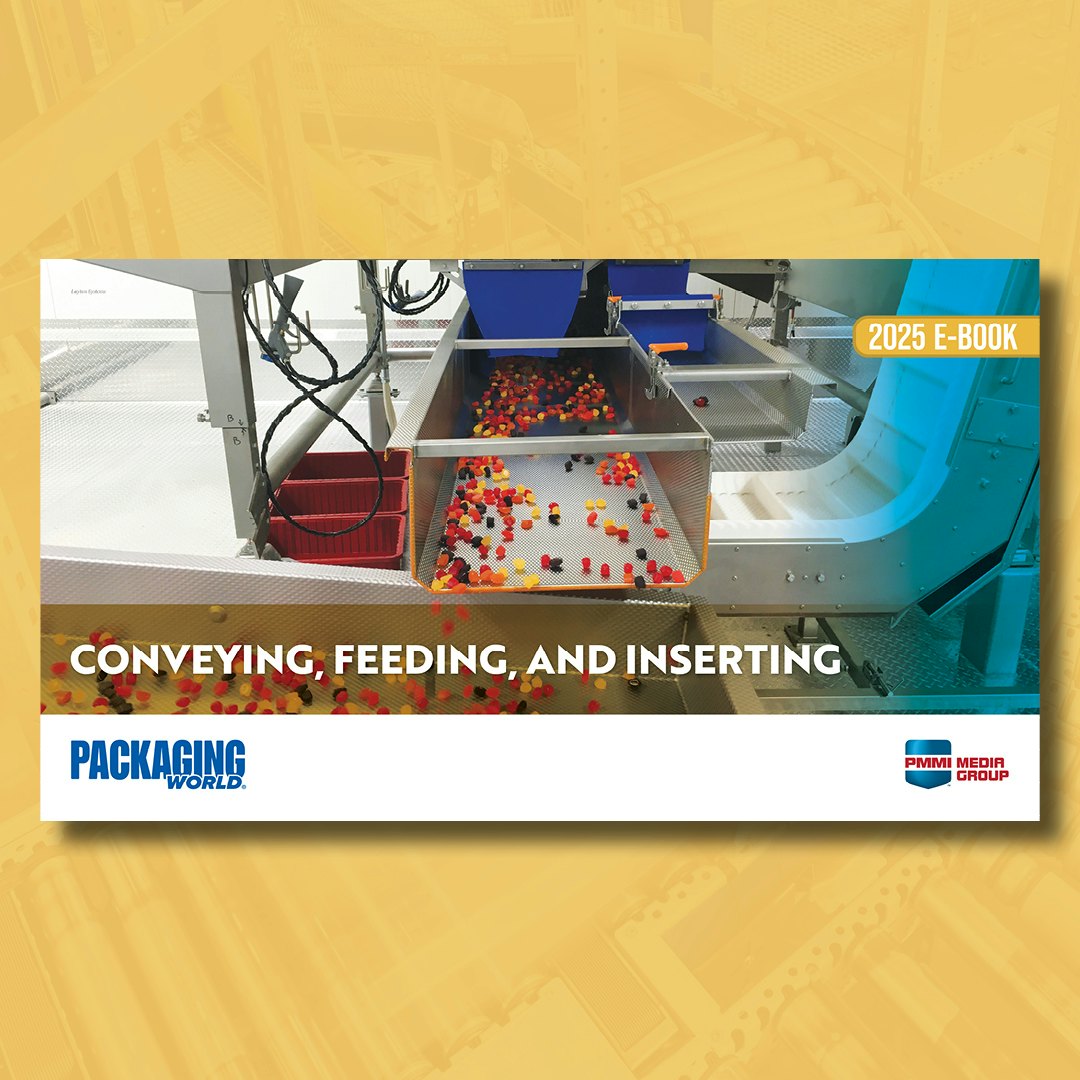

Machinery Basics

Conveyor setup secrets from top CPG manufacturers

7 proven steps to eliminate downtime and boost packaging line efficiency. Free expert playbook reveals maintenance, sequencing, and handling strategies.

Read More

Researched List: Engineering Services Firms

Looking for engineering services? Our curated list features 100+ companies specializing in civil, process, structural, and electrical engineering. Many also offer construction, design, and architecture services. Download to access company names, markets served, key services, contact information, and more!

Download Now