A proposed rule that would considerably lengthen drug “package inserts” has packaging executives aghast at the cost estimates popping up on their calculators. The point of the Food and Drug Administration’s proposed rule, issued last December, is to make the inserts more readable so that physicians actually use them. If that happens, a concomitant reduction is likely in drug-prescribing errors from factors like drug interactions. One top packaging expert at a major pharmaceutical company, who requested anonymity, admits that the current inserts are “preposterous.” He adds, “They are impossible to read and follow.” He doubts any company has a problem, at least conceptually, with changing the inserts to be more readable. But the FDA’s plan for making the inserts more useful has rankled industry regulatory and packaging officials. For example, the FDA wants companies to add a half-page “Highlights” section to the beginning of the insert. It would encapsulate the most important information, which would be provided in full elsewhere in the remaining part of the insert. The FDA would identify the general categories of information that must be included in the “Highlights” section, but companies would have some leeway as to exactly what to include. For example, information that is most relevant to clinical prescribing situations would have to be included in the “Highlights” section dealing with “Precautions and Warnings.” It would be up to the company to decide what information to print there. In addition, there would be minimum standards for certain critical graphic elements on the insert. FDA’s proposed rule says that the insert would have to be printed in at least 8-point type. There is no current requirement.

Increasing the size The anonymous packaging executive estimates that most pharmaceutical companies use either 7- or 6-point type and most don’t go below a 5-point size. In making its cost estimates, the FDA used 6.5-point type as the ostensible industry average. With that as the baseline, the FDA estimated that the average length of a page of a current package insert would increase 59%. That estimate does not include the half-page Highlights section. Grace Deebo, director of global regulatory affairs for Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN, says the insert for Lilly’s Zyprexa, prescribed for schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, would increase in size from two to five pages. Lilly is now working on estimates of how much its insert printing costs would increase as a result. Not only will annual printing costs for longer inserts add up, so will one-time capital costs for label printing vendors and manufacturers that do their own inserts. These costs will certainly be passed along. The packaging executive who wants to remain anonymous says the problem is that the folding and cartoning equipment his company currently uses won’t be able to handle those new, larger inserts. “Our equipment has a maximum size sheet that can be used, and a maximum number of folds that can be made,” he explains.

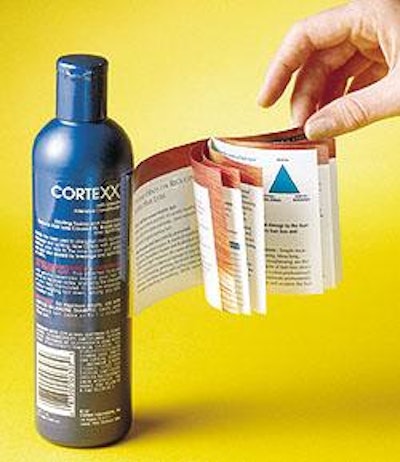

Adding cartons In addition, some products that now attach inserts to the outside of a bottle to eliminate an outer carton, may now have to be packaged in cartons since it would be unwieldy to attach a flapping stack of paper to the bottle. Lilly is also working up an estimate of how many of its products would need cartons, and what package development, production, and packaging would cost. Many companies have sent “back-of-the-envelope” calculations of cost increases to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the industry trade group. Alan Goldhammer, associate vice president for regulatory affairs at PhRMA, declines to share the preliminary data. In good part because of the time it is taking to fully develop authoritative cost estimates, PhRMA asked the FDA to extend the comment deadline and FDA agreed to give industry another 90 days. In the early months of the Bush administration, all sorts of industries were trying to sidetrack rulemakings that began under the Clinton administration. At the behest of business groups, Congress cancelled the OSHA ergonomics rule before it took effect. But Lilly’s Deebo does not think that the pharmaceutical industry will try to derail the package insert proposed rule. “That is what my gut tells me,” she explains. “We’ll try to make it the best for all concerned.”