Technologies that use heat in converting plastic into packages can be called thermoforming. With vacuum thermoforming, however, radiant heat is used to soften plastic sheet. Next, vacuum draws the sheet down into a female mold or down over a male mold, where the plastic takes shape. The plastic cools inside the mold. The shaped part is removed. Lastly, the part is cut and trimmed.

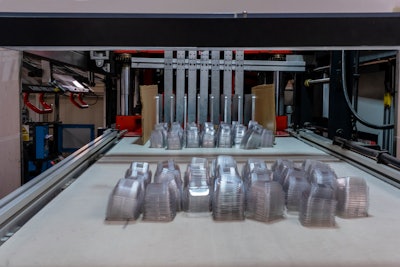

Packaging types include trays, kits, tubs, cups, blisters, and clamshells, used for food, medical device, and hardware—among other applications. As its description and applications might suggest, vacuum thermoforming is comparatively simple. But no technology is so simple that it is without pitfalls.

The central objective of vacuum thermoforming is the faithful three-dimensional rendering of a design, having a targeted wall thickness, uniformly distributed. That objective cannot be achieved if the design is poor. And since no one intentionally develops a poor design, it’s typically the result of not being aware of certain pitfalls that can manifest themselves aesthetically, functionally, and cost-wise. Of the various design features in which pitfalls lurk, three major ones are draw ratio, draft angle, and corners & radii.

Draw ratio is a calculation that divides the surface area of the mold by the footprint of the plastic sheet. Setting math aside, empirically, the more a plastic sheet is stretched (i.e., the deeper the draw), the thinner the walls. Draw ratio, therefore, is useful in determining the minimal starting thickness for the sheet. Without such knowledge, walls can end up too thin and subject to physical defects/damage. In contrast, walls that are thicker than needed waste money, in addition to violating principles of sustainability.

Draft angle is the measure, in degrees, of how much the sides of the mold depart from vertical. Using a vacuum thermoformed tray as an example, its tapered walls reflect the draft angle of the mold. A plastic sheet expands when heated and shrinks when cooled. The extent of those dimensional changes will vary, depending on whether the plastic is amorphous or crystalline (molecular chains arranged randomly or orderly, respectively).

Since only one surface of the sheet contacts the surface of the mold, the cooled plastic will pull away from a female mold but tighten around a male mold. For purposes of releasing the formed package, a female mold requires a lesser draft angle than does a male mold. A different type of release consideration applies to finished packages that are nested. The proper draft angle facilitates separation when being dispensed from a magazine, in package filling-line operations.

Corners & radii should be generously round. Sharp corners (90 deg, or close to it) are to be avoided because they require the plastic to be stretched farther into those recesses. The resulting wall thinning makes for weak spots that can rupture and leak. A related benefit of rounded corners & radii is that they have greater surface areas than do sharp corners; therefore, distributed stresses are lessened. Sometimes, female molds are operated with a plug assist, which pushes the softened plastic downward, facilitating the work of the vacuum. Plug assists are an aid to uniform wall thickness; nonetheless, they should not be regarded as a substitute for rounded corners & radii.

From a brand owner’s perspective, the quest is for a designer who is least susceptible to these (and other) pitfalls. Designs can originate from three sources: in-house, a design firm, and a mold designer firm. The last mentioned is where the most technical expertise is likely to reside. If the design originates from either of the other two, the mold designer should offer analysis, rather than just accepting what’s provided. If that sounds like a partnership, it’s because that’s what it should be—between in-house and outsourced parties.

A requisite first step is in-house consensus on what’s required in a design. That’s a challenge, given the competing interests of the various departments and the tradeoffs they necessitate. The agreed upon requirements must be translated into design alternatives, and ultimately, into a chosen one. Those outsourced parties brought into the process should be supplied with all necessary information, especially product strategy. Any concerns about “secrets” can be addressed contractually.

One-stop outsourcing is a valued convenience, but not always available. An example is a vacuum thermoformed package that is matched with a card (either as a lid or as an internal component), each sourced separately. The lead time for finalizing the card likely will be shorter than that for finalizing the plastic part. To be avoided is a situation wherein die-cut cards have been delivered, but afterward, there’s a last-minute change requirement in mold design. Such a sequence can compromise the match between components. Skilled project management and good communications are indispensable in shortening time-to-market.

Whereas some technologies are better suited to intricate designs, vacuum thermoforming lends itself to designs that are less so. But as discussed here, simplicity is no synonym for fool-proof.