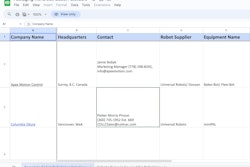

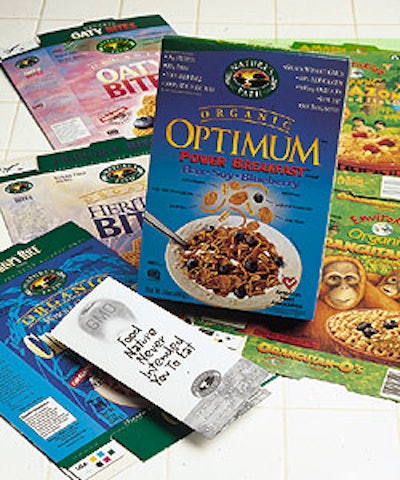

When Jon Stocking introduced the new packaging for Endangered Species chocolates in January 2001, he added a disclosure on the ingredients panel. For the first time, he included the notation “gmo-free soy lecithin.” Although the Belgian chocolate Stocking had been importing since the product’s beginning in 1993 had always been free of any genetically modified organisms (GMOs), he had never disclosed that before. Why now? “It was never the issue it is today,” the founder of the Talent, OR company explains. “It matters to people as it gets in the media.” It is starting to matter to the federal government, too. In part because of the visibility and concerns about genetically-engineered corn in foods stemming from last year’s Starlink episode, the Food and Drug Administration is now looking at what kind of “GMO-free” label disclosures can be legally made. Coincidentally, the agency’s publication of draft guidelines on how GMO-free disclosures should be worded on ingredient panels and on primary display panels comes at the same time the U.S. Department of Agriculture has published final rules on the use of the term “organic” on packaging and labels. Final rules published by the USDA last December, which essentially take effect on August 20, 2002, set up rules for using terms like “100 Percent Organic,” “Organic,” and “Made with Organic Ingredients.” All organic foods are GMO-free. Many GMO-free foods, although not Endangered Species chocolates, are organic. So these new packaging and labeling dictates will affect a sizable chunk of the retail food industry. Both actions will have a major impact on companies like Endangered Species and Nature’s Path Foods, Delta, British Columbia, Canada, a manufacturer of organic breakfast cereals since 1985. Nature’s Path makes both “organic” and “GMO-free” claims on its packages. Nature’s Path displays an “organic” claim in a prominent place on the front panel of its Optimum breakfast cereal, and also makes a “Grown Without GMOs” claim at the top of the front panel, along with nutrition claims.

The organic rules To be able to use the term “organic” after August 2002, Nature’s Path will have to be able to prove that the cereal contains by weight, excluding water and salt, at least 95% organically produced raw or processed agricultural product. The product can contain up to 5% non-organic materials as long as they are not produced using banned methods such as sewage sludge or ionizing radiation. Currently, Arran Stephens, the founder and president of Nature’s Path, uses a company called Quality Assurance International (QAI) in San Diego, CA, to come into the United States plant in Blaine, WA, to certify that his cereals are “organic.” The problem is that there are only about 49 certifying agents across the U.S., according to Richard Mathews, a USDA official, and they all have their own ideas about what constitutes an “organic” product. That will now change because as part of the USDA final rule the agency will accredit all certifying agents, and each will have to use the same standard, the one laid out in the USDA final rule. If the company wants to use the USDA organic “seal” after August 2002, it will have to be certified by an accredited company. Mathews says the USDA will release a list of accredited certifying agents by February 2002. The third category of package claim is “Made With Organic Ingredients.” Here, a product has to be more than 75% organic. In the case of a soup, for example, the package can say “Made with organic potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers.” Regardless of the number of organic vegetables used in the soup, up to three can be named. Alternatively, the company could say “Made with organic vegetables.” Nature’s Path’s Stephens believes that QAI will be accredited by the USDA, and that he will be able to continue to use the “organic” claim because the product meets the new USDA requirements. Nonetheless, he is going to redesign the packages for the 25 or so products that he expects to earn the “organic” label because he wants to give a prominent place on the package to the new USDA “organic” seal. The seal itself is nothing fancy. It is a circle enclosing a white upper half, against which is printed USDA, and a bottom half that’s grey or green to resemble a cultivated farm field. “That seal will definitely help our products that are made in the U.S.,” Stephens says. The Blaine, WA, plant manufactures millions of boxes of cereal a month. But the packaging changes to accommodate the seal won’t be all that expensive because he does his package design digitally. Stephens says he will have to spend about $50ꯠ for new art plates. The problem is that when the USDA organic rule goes into effect in August 2002, companies can continue to use the seals of their certifiers, or the USDA seal, or both, or neither. Asked whether that is a formula for consumer confusion, the USDA’s Mathews answers, “Probably.” But he believes almost all products will use the more credible, influential USDA seal.

GMO guidance While the organic labeling rule is a done deal, the FDA draft guidance on use of terms like GMO-free is a work in progress. However, based on what it heard at the three public meetings in 1999, FDA agreed that some labeling guidance was necessary, both for products that want to say they are “GMO-free” and those that want to advertise they contain genetically engineered ingredients, for example, a soybean oil engineered to be of lower fat content. But it is the GMO-free type claims, which are much more popular, that are the real target of the guidance. John Faulkner, spokesman for Campbell Soup Co., Camden, NJ, says that many of his company’s products contain infinitesimal amounts of genetically engineered corn or soybeans. Typically, those ingredients are used as bindings in soups and sauces. The corn in Campbell’s soups is not genetically engineered. Campbell does not make any genetically engineered disclosures on its product labels, nor is it required to do so. But Faulkner notes that if Campbell came up with an ingredient that was genetically engineered to help fight cancer, for example, it would probably talk about that ingredient on a product label. Campbell and the rest of the “conventional” food industry were delighted with the FDA decision to stay with its current position. Rhona Applebaum, executive vice president at the National Food Processors Assn. (NFPA), says, “We believe it is essential that mandatory labeling be reserved for information that is material—that is, information that goes to the safety, health, composition, or nutritional value of the food.” The FDA draft guidance says that consumers don’t understand the term GMO. It states: “Most, if not all, cultivated food crops have been genetically modified. Data indicate that consumers do not have a good understanding that essentially all food crops have been genetically modified and that bio-engineering technology is only one of a number of technologies used to genetically modify crops.” So based on the draft guidance, labels could not say “GMO-free.” Claims like Nature’s Path’s “Grown Without GMOs” would also appear to be out of bounds. Allowed package claims would be descriptors such as “We do not use ingredients that were produced using biotechnology” or “This oil made from soybeans that were not genetically engineered.” Nature’s Path’s Stephens is not too excited about those alternatives. “You can’t put a long sentence in three-point type on a label and have any kind of consumer recognition,” he complains. Jon Stocking at Endangered Species is more accepting, maybe because he only makes the GMO-free soy lecithin claim in already small type, and only in his ingredient panel. He says he would be comfortable with the FDA’s preferred wording: “This chocolate is made from soy lecithin that is not genetically engineered.” Numerous companies, according to both Arran Stephens and Jon Stocking, have been making organic claims that couldn’t be backed up. With a federal standard for organic labeling in place, and another for GMO foods on the way, the “bad apples” will be faced with federal enforcement unless they either change their ingredients to conform to federal standards, or change their packaging to ditch unsupportable claims.