It is difficult to generalize about shopping behavior and “what works” in terms of packaging and point-of-sale marketing. From observing shoppers in store, we’ve seen their priorities vary widely from one category to the next, and that the role of packaging may be quite different in a “grab and go” convenience store as opposed to a club store or a “big box” electronics store (where the products are often displayed).

However, if we can point to one consistent reality across categories and channels, it is that marketers and shoppers approach the in-store experience from different perspectives: Marketers typically think in terms of their product offerings. Therefore, they name and package their products in terms of ingredients, features, and price points. But shoppers typically think in terms of users and usage occasions. They enter the store seeking products for specific people and situations—and therefore want to know if a product is right for their needs.

At the shelf, these two mind-sets often collide, and the shopper looking for personal relevance (Who and what is it for? Is it right for me?) instead encounters packages full of ingredients and product features. Examples of this ‘great divide” between marketers and shoppers abound in virtually every product category:

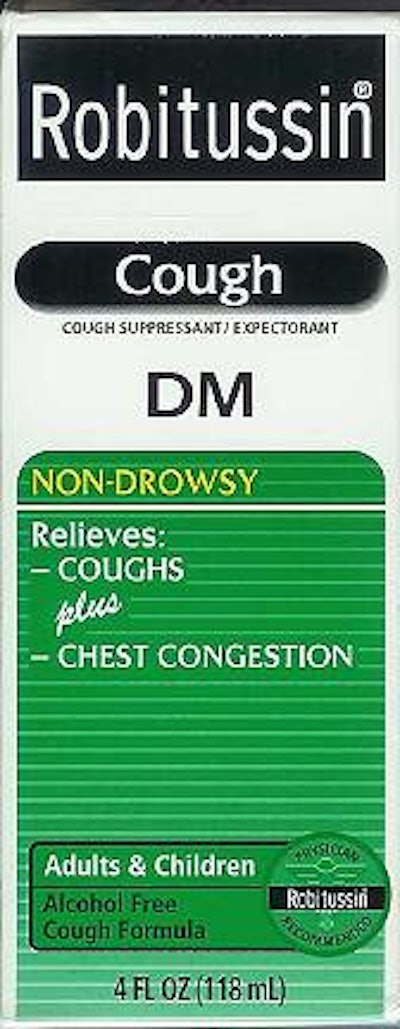

• In analgesics, cold medicines and other health care products, shoppers want to know what the product treats (cough, cold, etc.) and when to take it (Will it make me drowsy?). However, packaging frequently emphasizes product form (liquid-gels, caplets, etc.) and efficacy claims (12-hours, Extra Strength, etc.)

• In drain cleaners and household items, shoppers typically think in terms of specific usage applications (my kitchen sink, my bathroom, etc.), but instead encounter a myriad of product forms (Oxy, Foam, Gel, etc.).

• For software and technology products, shoppers often approach the category thinking in terms of compatibility (Will it work with my computer?), but instead find packages full of claims and numbers.

Limitations of ‘Good, Better, Best’

Perhaps the most common manifestation of this “great divide” between what consumers want and what marketers offer is the positioning and packaging of products on a “good, better, best” continuum. This approach, commonplace in products from cake mixes to batteries, is certainly understandable from the marketers’ perspective. They are investing in product innovation and need to persuade shoppers to pay more for new ingredients and features. However, “good, better, best” leads to confusion in many categories, as shoppers are overwhelmed with options and face packaging that typically speaks to new features rather than their underlying needs.

The surge protector category serves as one illustration. Shoppers typically approach the category with a specific application in mind. They want a surge protector for their computer or perhaps for their new stereo system. However, packaging highlights dueling claims, most notably a “protection level” (550 Volts, etc.) that is meaningless (and even counter-intuitive) to most shoppers. In addition, a competitor can always “scream louder” or introduce a higher number. Clearly, there is an opportunity to break through the clutter of numbers and claims via packaging that positions one product for use with stereos and another for use with home PCs.

On another level, in a “good, better, best” packaging system, a new high-end product introduction often undercuts the rationale for other products to exist as anything other than a value offering. After all, once you have “Cascade Complete,” why would anyone purchase Cascade Regular? Once you have “Extra Strength” painkillers, would anyone really want to purchase a product that isn’t Extra Strength—and thus works less well?

Bridging the gap through packaging

Of course, the answer isn’t necessarily to stop introducing new and better products. Instead, the key is to use naming and packaging to segment products in a manner that is intuitive and relevant to the shopper. With this thought in mind, consider these three ideas for successfully executing a “good, better, best” strategy:

1. Link to “quality levels” to usage occasions and scenarios. There is nothing wrong with highlighting the additional features and benefits associated with a new or higher-end product. However, packaging can make quality tiers more relevant and powerful if it links specific products to underlying shopper needs. In the paper category, Jet Print packaging does this effectively by using the primary visuals to link different products to different usage occasions (i.e., Professional = wedding; Everyday = scrap book; etc.). Robitussin Cough cartons are another example, with their front-panel bullet point system.

2. Visually build across packages or subbrands. It’s also important that packages within a brand family allow for quick comparisons. Perception Research Services (PRS) has found that it is powerful for a more premium package to “build” on a lower-end model by showing that it has everything in the lower-end version plus a certain added feature or benefit. For more technical products, back-panel comparison charts can serve this need. However, for less-complex items, it is critical to display comparison charts on the front panel. For example, Kodak has done this in a visually intuitive way by letting two bullets represent lower-end products and then building to four bullets on higher-end models. Conversely, having four claims on one package—and four different claims on another--makes comparisons very difficult for shoppers.

3. Use structural innovation to delineate higher-end products. Across our studies, PRS has consistently found that shoppers typically associate innovative packaging structures (new delivery systems, shapes, sizes, etc.) with revolutionary and higher-end product offerings and that the use of unique materials (such as metallic foil) can have a powerful impact on product expectations and brand imagery. In addition, PRS Eye-Tracking research has consistently shown that unique packaging structures help brands to break through shelf clutter and generate consideration at retail. This challenge shouldn’t be underestimated, since many new-product failures are linked directly to a lack of retail visibility and thus limited shopper awareness.

To a marketer introducing a premium product line, the implication is clear. An investment in packaging innovation is very likely to be worthwhile because differentiating on an intuitive, visceral level is critical to generating consideration, conveying added value, and facilitating shopping.

Slicing categories in new ways

While packaging innovation and execution can help marketers to connect with shoppers, some of the most successful product introductions are those that slice categories in new ways. Success comes when marketers break away from traditional product-based naming and segmentation and instead organize products and packages around shopper priorities and thought patterns. Here are some examples of where this approach is playing out well:

• In orange juice, Tropicana has introduced its Tropicana Essentials line, which is organized around end-benefits (Healthy Heart, Kids, etc.) rather than ingredients.

• In aspirin, Bayer has introduced Women’s Aspirin, which speaks to the intended user rather than product form.

• In snacks, Frito-Lay has rolled out 100 Calorie Mini-Bites, which approach two primary shopper concerns—health and weight control—in a new way, as opposed to yet another “Diet” or “Light” or “Baked” product.

When shopper-driven product organization is combined with effective packaging execution, the results overcome “the great divide” between marketers and shoppers—and ultimately drive sales. Certainly, marketers who invest in understanding shopping behavior at the point-of-sale—and in executing packaging that aligns with and speaks to shoppers’ decision processes—are sure to be well-rewarded.

The authors, Scott Young and Lily Lev-Glick, are from Perception Research Services, a company that conducts more than 500 custom studies annually to guide packaging and point-of-sale marketing decisions. They can be reached at 201/346-1600.