Healthcare packaging professionals must feel like the patient getting her blood pressure taken as the doctor squeezes the bulb and inflates the cuff to the point where she feels her arm’s going to burst. Packagers are being squeezed by the stress of keeping up with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, validation issues, and new technologies such as advanced machine controls and radio-frequency identification (RFID).

A host of broader, often global issues understandably raise the blood pressures of healthcare packagers. These include developing packaging to improve patient compliance with drug regimens, serving an aging baby-boomer population, aiding hurricane victims, packaging drugs for a potential bird flu pandemic, and readying drugs to counter the possibility of bioterrorism.

Add to that the growing global problem of counterfeiting, evaluating outsourcing/contract packaging, coping with resin price hikes, and increasing sales and profitability at a time of increased public and media scrutiny, and you can begin to understand why healthcare packaging professionals are under pressure.

According to the Strategic Research Institute, “the issue of patient compliance is of vital importance to the healthcare industry as non-adherent patients account for over 125ꯠ deaths annually.”

SRI held a two-day “meeting of the minds” in mid-November in Philadelphia to address the issue, with innovative packaging design scheduled as one of the topics of the discussion.

Amid media reports indicating that the United States is unprepared to handle a potential Avian flu pandemic, the FDA in late October announced the formation of a Rapid Response Team to ensure that antiviral drugs, such as Roche’s Tamiflu, are available when needed. “Making sure Americans are protected against an outbreak of Avian flu is one of the FDA’s top priorities,” said Andrew von Eschenbach, MD, and acting FDA commissioner. “Using the Rapid Response Team approach, we believe we could review a complete drug application in six to eight weeks.” That would add more pressure for packaging materials and lines to be ready.

‘One-piece’ flow; globalization

Each of the experts listed on this page was asked to identify the most critical packaging issues he or she expects to face in the next year or two. John White of Smith & Nephew Orthopedics identified three main issues, beginning with globalization. “As we expand into new global markets, we need to ensure that our packaging processes are consistent and effective, even though we may use local equipment and packaging supplies,” he says. “This requires developing expertise at the plant level and managing these resources from overseas.”

White believes, “In addition to our traditional role as engineers, we are also rapidly becoming flexible trainers, as we start up global operations. Starting an operation in Europe presents different challenges than starting one in the Far East, even though the products could be the same.”

His second critical issue concerns “smaller production runs, with equipment that is both flexible and easy to change over. Our goal is to achieve a one-piece flow packaging operation,” he says, defining the term as, “a lean manufacturing concept in which parts are produced one at a time (or in small batches).

“Companies that have effectively implemented one-piece flow,” White says, “benefit from less work-in-process, quicker throughput times, increased output, enhanced quality, ‘freed-up’ production floor space, and a reduction in machine and operator errors.” He declares, “This is a major change from traditional methods of packaging. As we transition, we have seen packaging lead times cut by 40- to 50-percent. Our goal is to create processes that can move to another room or building at a moment’s notice.”

White lists “smaller and standardized packaging” as his third key trend or issue. “Hospitals that use our products have limited storage space, and they require that our packages be as compact and uniform as possible. Even though the number of our packaging stockkeeping units is constantly growing, we have shown overall reductions in the number of packages.”

Getting qualified engineers

Lockwood Greene’s Nancy St. Laurent admits that keeping abreast of technology is a challenge. “We need to be on the leading edge of technology, so we must be prepared for new line integration features, new and different packaging, trends such as RFID, and our engineers need to attend trade shows, search the Internet, and read trade magazines for new and different technologies.”

Beyond these technology challenges, she notes, “drug administration is constantly changing. The FDA initiative for bar coding of unit-dose products for hospitals is one example of an emerging technology. Companies have to employ different printing options, whether that is performed by the supplier of printed material, or on the equipment used to assemble the package.”

St. Laurent’s most pressing issue, however, is “getting enough qualified engineers for pharmaceutical packaging operations, including sterile filling. There are very few packaging engineers who are thoroughly knowledgeable of the technology, of the specific equipment used in pharmaceutical packaging, or with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), and the efforts needed to validate this equipment.”

Dana Guazzo agrees with St. Laurent’s concern, identifying the “lack of expertise ranging from early development and validation stages through product support and post-launch package changes. Novel unit-of-use packages, senior-friendly designs, and unique routes of product delivery are examples of the many opportunities that require a team of package development engineers.”

Workplace issues

Beyond the lack of qualified engineers, other personnel or workplace issues were also raised. White says, “In some companies, there’s a perception that engineers are far removed from the actual happenings on the shop floor. At Smith & Nephew, our engineers are actively involved in projects with the production department. We have learned a great deal from each other. I think this jump in technical and practical expertise has greatly enhanced our packaging operations.”

St. Laurent believes, “more training is always necessary in packaging operations,” even though it can be challenging. She says, “As old equipment is replaced, upgrades to machine controls are inevitable. With bar codes and RFID, more and more vision [systems are] being applied, requiring extensive training.”

Kristen Giovanis explains that her company, KJ International, specializes in helping pharmaceutical and medical device firms translate packaging copy into different languages. This includes labels for primary and secondary packages, technical manuals, usage instructions, etc. Electronic labeling is a key area of focus for KJI as well. This means providing label information in an electronic mode such as a CD, or via a Web site, as opposed to traditional printed materials.

Giovanis sees the need for “more training on systems and processes for companies seeking technical solutions to electronic labeling. Also, technical writers and internal support staff will need to work within [these] new processes.”

Guazzo is the founder and sole member of RxPax, a pharmaceutical package development consulting firm. She says, “the majority of pharmaceutical and medical device companies I am familiar with are attempting to do more work, do it faster, and with fewer staff. Management may not even perceive the need for early product development packaging support. This can lead to improper material or component choices and incomplete package development efforts. As a result, multiple problems typically begin during development and haunt the firm all the way through to manufacturing. For example, a poor package can lead to product degredation during stability studies, a sporadic loss of package integrity during larger-scale manufacturing operations, delays in product approvals, and even product recalls due to a less-than-robust package.”

New product packaging issues

Beyond this workplace pressure, Guazzo cites package protection as a major issue. She says, “Many pharmaceutical and medical device combination products include potent active ingredients and may be reactive to package headspace gases or extractables. Parenteral products are frequently filled aseptically, not terminally sterilized, and formulated without preservatives.

“This is complicated by the fact that companies are assembling packages at higher speeds,” Guazzo continues. “The manufacture of the package components themselves must be more specific, controlled, and monitored. Also, the ability to identify and prevent package integrity flaws in the assembled package is more critical than ever.”

As science advances the use of biological products, Guazzo foresees another critical issue. “More biological products are required to be stored at cryogenic temperatures, under conditions that no traditional package is designed to tolerate. That can dramatically affect the viscoelastic properties of the package components. For example, during cryogenic storage, a package’s seal integrity may be affected, resulting in an influx of atmospheric gases. For products stored in dry ice, carbon-dioxide ingress can cause a product’s pH to shift, and the product to degrade. Another consideration is the potential ingress of microorganisms, especially as the product is warmed prior to use.”

Validation issues

Validation continues as one of the most discussed and most challenging on the healthcare packaging “beat.” St. Laurent reports, “We stay closely attuned to the FDA, the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE), and other organizations. Validation still requires an inordinate amount of time and money. There is a huge expense in materials that are wasted in some cases, and I feel way too much time is spent on some equipment that does not require extensive validation,” says St. Laurent. In particular, she cites case-packing, palletizing, and cartoning equipment.

“Any printing inspection that is done on these [packages] needs to be validated, but a lot of other things that are validated are more cosmetic in nature. FDA requirements call for things to be validated that affect the potency, safety, purity, and efficacy of a drug, and a lot of packaging equipment does not affect these factors. The most challenging part of validation of packaging machinery continues to be the lack of time,” says St. Laurent.

Guazzo offers the following validation advice: “The more knowledge, research, and vision devoted up front, the faster and smoother the development, validation, and approval process. Communication between product and package development, engineering, regulatory affairs, and marketing must be constantly flowing. Outside the organization, the package development staff needs to link closely with suppliers of packaging materials and components.”

White adds, “Validation has become more standardized now with the tools available through Six Sigma methodology such as failure mode and effects analysis, design of experiments, and process capability. These are excellent ways to predict and address potential situations prior to putting a process into production.”

In part two, these healthcare packaging experts discuss counterfeiting, packaging and personalized medicine, oil/resin pricing concerns, and material and machinery advances.

See sidebar to this article: Radio-frequency identification

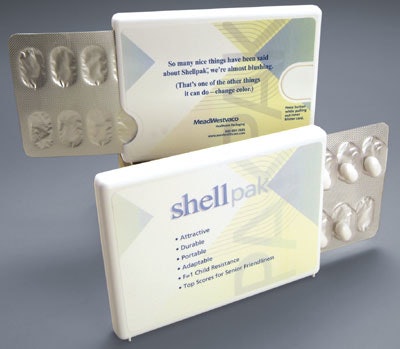

See sidebar to this article: The end of drug bottles?

See sidebar to this article: Edible strips now deliver drugs

See sidebar to this article: The experts