Caught in the vise-grip of daily crises, compressed schedules and shrinking staffs and budgets, today's packaging professionals are sending a clear message: Packaging people are asked to do too much, too fast, with too little.

That's the conclusion of men and women readers who responded to Packaging World's exclusive salary and job satisfaction survey. Sent earlier this year to 2ꯠ readers with engineering, production and purchasing responsibilities, 14%, or 280, responded. Readers work for large companies as well as small throughout the U.S., representing a variety of industries, including food, beverage, pharmaceutical, medical and industrial.

This article will showcase the overall highlights of the survey. Also in this issue is a report on specific salary and job satisfaction results from respondents with packaging engineering responsibilities (p. 60). Subsequent issues will cover respondents with purchasing responsibilities, as well as department managers and plant managers/vps.

Gender bender

In looking at the overall data, some interesting facts surface. The first is apparent gender inequality.

Packaging has a shaky footing when it comes to gender equality, at least among our survey respondents. Among those respondents, slightly under one quarter were women (Chart 2, p. 53). And 75% of women responding to the survey work in purchasing. Just 15% of women respondents are department managers, and only 7% of women respondents work as engineers.

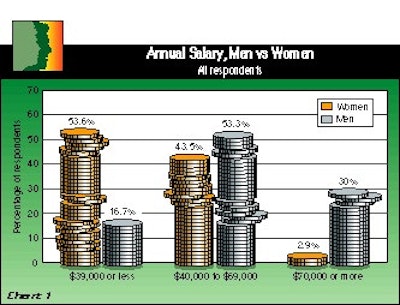

The survey also showed that women respondents tend to earn salaries at the lower end of the salary spectrum compared to male respondents. For example, over half of female respondents earned $39ꯠ or less in the last year, versus about 17% for men (Chart 1, p. 52). At the high end of the pay scale, 30% of male respondents earn $70ꯠ or more; less than 3% of women are similarly rewarded.

The lower salary figures for women respondents could be explained, however, by several factors. First, women who responded had less experience than men: only 15% of women had over 15 years' experience, versus almost 45% for men. Second, there was a difference in education. About 40% of women respondents indicated the highest level of education completed was high school or a two-year technical degree. That figure was only 28% for men; the rest had a college or post-graduate degree. Finally, of those respondents who hold management positions, only 14% are women. This last statistic is telling in itself.

What's interesting is that the percentage of women respondents that reported being satisfied with their jobs (48%) was nearly equal to the percentage of men who are satisfied (51%).

Northeast earns most

Survey respondents in the Northeast reported the highest salaries, with 57% of respondents in that part of the country earning $55ꯠ or more. Respondents on the West Coast were next at 47%, with the Southeast (44%) and Midwest (43%) trailing.

The survey also revealed something that this magazine's circulation department has known for a while: people in packaging move around. Nearly half of all respondents have been in their current position five or fewer years; 17% less than two years (Chart 3). Over 20% of respondents report being promoted to a new job in the last year, and another 15% said they changed jobs or switched to a new company during the same period.

While packaging people frequently change jobs, they're not without experience. To the contrary, about 75% have been in their packaging career for more than 5 years, and more than half have been in packaging for over ten years.

Packaging people also appear to be well educated. Nearly 70% of this survey's respondents report a college or post-graduate degree (Chart 5). These numbers, incidentally, remain fairly consistent across all job titles.

The survey uncovered that respondents who completed specific packaging coursework either in trade school, college or after college were likely to earn more money. Those without packaging-specific courses reported lower salaries (Chart 4, p. 54). However, only a minority of respondents (just over 10%) reported having taken such courses in school (Chart 6). It may be tenuous to suggest that obtaining packaging education will directly result in higher earnings, but our survey does show a correlation between the two.

Purchasing not satisfied

The survey questions about job satisfaction struck some universal chords among all respondents.

Winner for most disgruntled group of respondents: purchasing agents. More than 25% report that they are dissatisfied with their jobs. One purchasing agent at a small Northeastern food company wants to spend "less time performing clerical duties and more time purchasing!" Many others voiced similar complaints. A buyer/planner at a pharmaceutical company groused that "firefighting and clerical responsibilities prevent proactively looking for better ways to do things."

Dissatisfaction among other packaging people was less pronounced: only 13% of the packaging engineers in our survey say they are dissatisfied with their jobs; 15% of department managers and 9% of plant managers and VPs also report they're unsatisfied.

When asked to rate the degree of satisfaction with specific aspects of their jobs, advancement potential seemed to rate the lowest. Those in purchasing positions were most likely (48%) to be dissatisfied with advancement potential; packaging engineers were close behind them, with 46%. Perhaps understandably, department managers (33%) and plant managers/VPs (24%) were less unhappy about advancement opportunities.

Purchasing respondents also were least happy about their salary. Nearly 40% were dissatisfied with their paycheck. In contrast, only 15% of packaging engineers in the survey said they were dissatisfied with their pay.

Packaging engineers were the happiest group (46.5% satisfied) when asked about the number of hours worked; department managers were at the opposite end, with only 35% satisfied.

Crisis management 'routine'

To encourage reader comments, the survey asked what they would like to spend more time on at work, and what prevents them from doing that. (For a summary of responses, see p. 53.)

Important disclaimer: it should be stated that exactly half of our survey respondents indicated they were satisfied with their jobs. Another 32% were neutral, with only 18% dissatisfied. The comments that make up the remainder of this story should be considered in the context of the above numbers. In other words: we asked readers to gripe-even if they were satisfied with their jobs-and they complied.

Perhaps PW skewed the results by suggesting an example, "putting out fires." The "fire" issue seemed to resonate profoundly with packaging people in all industries, functions and levels.

"Your example pretty much describes my feelings," wrote a packaging engineer at a large food company in the Midwest. "Crisis management is the routine," agreed a purchasing agent at a small Southwestern food company.

And "putting out fires and motivating subordinates" is what one plant engineer at a cosmetics company in the Northwest says prevents him from spending more time on "special projects and increasing overall plant efficiency."

A maintenance supervisor at a small Midwestern food company circled our example and asked, "Is this an industry trend?"

Compressed timelines

At the same time packaging professionals are besieged by defusing day-to-day crises, they're also grappling with shrinking timelines that further compress development and production schedules. (For a look at how this problem affects the downsized packaging operation at Pillsbury, see Packaging World, Aug. '97, p. 72.) Several packaging engineers griped about being overloaded with projects, lacking the time to give each the attention it deserves.

Purchasing, too, piped up: "New product development timelines prevent thorough vendor analysis," says a purchasing agent for a large Midwestern food company.

Says a purchasing agent at a small food company in the Southwest: "Short cycles of production forecasting causes more time spent scrambling for suppliers instead of being able to concentrate on regular duties."

Production schedule changes seem to bother some. "Schedules change daily," complains a packaging department manager at a small food company in the Southeast. That can create a ripple effect through other departments, especially purchasing.

"Constantly being reactive to shortages or schedule changes keeps me from being proactive," verifies a director of purchasing at a small Northeastern food processor.

And one purchasing agent at a small Midwestern manufacturing firm admits that even suppliers can be caught up in the grind as a result: "We have too many emergency situations and often become unrealistic in our expectations of our vendors," he writes.

Stretched too thin

Besides crisis response and shrinking schedules, PW readers report being squeezed by other forces: being asked to do more with less. The survey respondents document the trend towards shrinking packaging staffs and budgets. Over 20% of PW's survey respondents report packaging staff cuts in their companies in the past year.

"Downsizing and budget constraints do not allow for sufficient staff," writes a Southwestern purchasing manager for a maker of medical products. He continues: "I spend too much time doing detail work and putting out fires."

A VP of materials management at a medium-sized Mid-Atlantic food company says "a lack of staff prevents spending more time . . . planning and scheduling."

Most tellingly, over 60% of all respondents say they've had to take on more responsibilities without more pay in the last year. A purchasing agent at a pharmaceutical company says he has "too many job responsibilities, and can't spend enough time on each."

The angst of some respondents is almost tangible. Says a manager of purchasing, traffic and inventory control at a small Southwestern chemical company: "I feel pulled in so many directions most of the time that I feel I am not doing the best job that I know I am capable of doing." She adds: "I wish I had more resources at my disposal to do a more efficient job."

No time for 'rainy day' projects

With so many tasks on PW's readers' plates, something has to give. A number of respondents indicated that they are so busy with the day-to-day grind that they don't have a chance to tinker with new ideas for the future. A packaging R&D engineer at a large Midwestern food company said she doesn't have enough time for "R&D of new and unique packages."

A director of packaging purchasing at a medium-sized food company in the West has time to dream, but little else: "I'd like to develop the package of the future," she wrote.

Several respondents suggested that they'd like more time to visit suppliers, customers, other manufacturing operations to help stay current with what's new. A pharmaceutical packaging engineer in the Northeast writes that he'd like to "Go out in the field more often to see competitive packages and [better understand] customer needs." A packaging engineer at a medium-sized cosmetics firm in the Northeast agrees. She'd like to "take more trips to primary packaging suppliers to learn first-hand how packages are made."

Many respondents decry the pace and would like just a moment to catch their breath and do some "rainy day" items. Several respondents desired to, in the words of one packaging engineer at a food processing firm in the Northeast, spend time on "updating documentation, standards and specification development."

Another engineer at a medium-sized food company in the Northwest wants to "spend more time trying to improve the big picture rather than putting out fires." An engineer at a food company in the Southwest would like time to "determine the true root causes for problems. There isn't enough time to perform accurate studies and subsequent analysis," he adds.

Many packaging people say they spend so much time dealing with crises that they have little time to focus on what their companies want most: determine ways to reduce costs. One VP of purchasing based in the Northeast at a haircare products manufacturer would like to spend more time "Looking into additional value analyses and opportunities."

Another purchasing manager at a medium-sized manufacturing company in the Southeast says she would like to pursue "better sourcing for price and quality. [We have a] small staff, with not enough time to work on job proposals." A purchasing agent at a small Midwestern cosmetics company says she wants more "supplier interaction to improve quality and reduce costs." Still another purchasing agent at a small Southwestern food company needs "more time to seriously consider packaging and vendor alternatives."

Sheer lack of time prevents many respondents from cultivating new sources of supply. "[There's] not enough time available to analyze new sources, competitive quotes, etc.," writes a Southeastern purchasing/traffic manager at a chemical manufacturer.

A director of purchasing at a small food manufacturer in the Northeast wishes he could spend time "find[ing] improved and unique packaging materials."

Packaging professionals from all departments, industries, company sizes and regions have spoken clearly. While most-but by no means all-are satisfied with their paychecks, hours, and work environment, a clear portrait has emerged. It depicts packaging professionals up against a crush of trends that only threatens to increase in intensity in the coming years.

The anxiety of respondents might be best summed up in this comment from a plant manager at a small, family-owned meat products company in the Midwest: "By the way, where is my eight-day week and five-week month? I need it!" c