Mechanical drive systems perform well where designs can be specifically optimized to run one product. However, today’s manufacturing environment requires increased responsiveness and versatility, particularly where packaging is concerned.

Servo drive systems are ideally suited to these challenges, coping well with changing demands. They are capable of high speed and high accuracy, and, by synchronizing actions and entire machines, provide continuous motion. Being programmable, they can be modified as required, leading to fast changeovers so that shorter batch runs are cost-effective.

Enhanced diagnostics of servo systems enable increased monitoring of the performance and health of packaging machines. Predictive maintenance becomes more realistic, and potential failures can be caught early on. During jams, help screens can provide assistance with fault diagnostics to better pinpoint root causes. Finally, all production data can be made instantly available both locally, to operators, and to management for long-term planning and optimization.

One reason that servo drives are finding their way into an increasing range of packaging machinery is that an expanding number of controls systems suppliers, aggressively competing for a share of this growing market, have developed new systems with an emphasis on ease of use at significantly reduced prices.

In turn, more machinery users have been drawn to consider how the technology will help improve their daily operations, particularly meeting the demands of their retail customers for variety and lower prices. The flexibility of servos promise to simplify adopting servo-based machines to accommodate new product launches or extensions.

Many packagers find that though production volumes may remain similar to those of previous years, the total is now spread over an increasing range of new flavors and varieties. The result is shorter runs and more changeovers, all of which take time and leave valuable resources idle.

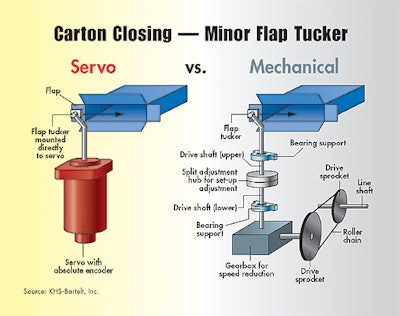

Modern drive systems are providing some of the answers, carrying out the same machine operations, but in a much more flexible fashion than the typical mechanically controlled machine, with its main drive shaft and mechanical linkages performing discrete operations such as the cam action of a sealing jaw or knife. Indeed, such mechanical linkages rely on gears or sprockets to ensure the correct speed ratio and that synchronization is maintained.

Introducing inaccuracies

To cope with different products on the same machine, a range of settings and change parts, relevant to each product, is typical. The trouble is that these change parts can take a long time to install and rely heavily on the skill of a technician or machine operator to set them up. This human intervention can introduce inaccuracies into the process.

So how do modern drive systems help? There are a number of different drive types and technologies available, from AC inverters, DC drives, servo and stepper drives, along with a range of hybrid technologies. Each has its place, with the selection being made on either cost or performance grounds. However, servo drive technology is having the biggest impact in high-performance packaging applications.

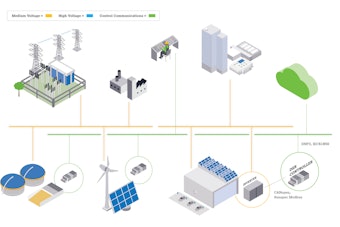

The basic configuration of a servo drive system consists of a servomotor to move the load, a servo drive that controls the motor, and some form of feedback from the motor to the drive that transmits speed, position, and torque data. These systems can operate in stand-alone mode or can be connected to an external control system, allowing complete motion control of multiple axes.

In a servo machine there is a main or master servo axis—which equates to the main drive shaft in a mechanical system—and any further servo axes, called slaves, are synchronized electronically to this master axis via software, instead of via a mechanical linkage.

These servo drive systems are sophisticated and simulate mechanical actions such as gear ratios, a cam-box, or lead screw. But because these functions are software-controlled, they can be programmed to quickly accept new parameters.

To highlight the benefits of servo versus mechanically controlled machines, consider the basic functions of a generic horizontal form/fill/seal machine.

In a mechanically driven machine there is a main drive, perhaps controlling the speed of the infeed conveyor. Further auxiliary actions are linked to the main drive—for example, forming and placing the product into the pouch, controlling the heat-sealing jaws, and so forth. These auxiliary actions are mechanically synchronized, often through gearboxes or cams, to the speed of the infeed conveyor. That way, any change of speed is then correctly seen across the entire machine.

The important difference of the servo control machine is that master and slave servos are linked by software. The master servo is continually reading actual machine conditions: the positions and loads given by feedback data. All slave servos then perform as directed in the control software.

To change the machine over to a new product, the operator simply loads the control system memory with all the new data, which could include numerous variables such as ratios, speeds, and product dimensions. This setup data may be selected from a number of pre-stored recipes made available through an operator touchscreen. Therefore, changeovers can be achieved at the touch of a button, downtime is kept to a minimum, and productivity is improved. Changeover on a servo machine also reduces the time spent making manual adjustments to the machine.

Another area to consider is machine throughput rates. In a mechanically controlled machine, where numerous actions are linked to a main drive shaft, it becomes difficult to change the individual speeds of these actions in isolation without affecting the rest of the machine or process.

For example, in an application using gravity filling there may be a need for a slightly longer filling cycle, perhaps because of variations in consistency of the liquid or powder. This would generally mean slowing the whole machine down to achieve this new fill cycle time.

If a servo-controlled machine were to face the same problem, it would be possible to design a control system to automatically compensate—within certain constraints—for variations in speeds of these individual actions.

Using the liquid or powder filling example above, if the operator wanted to add, say, two seconds to the fill cycle, the control system would compensate for this elsewhere in the machine. Indeed, the two seconds could well be made up through a combination of speeding up nonproductive return cycles, reducing acceleration times or increasing running speeds elsewhere.

Three generations

Lately, there’s been much talk of the different “generations” of servo-based packaging equipment. Although experts disagree what specifically constitutes each generation, there is broad agreement that so-called third-generation packaging machines—those designed from the ground up around servo technology—are best positioned to exploit the benefits of servo technology.

First-generation machines are those with mechanical drive systems. Second-generation machines are mechanical machines that have an added servo or two. In second-generation machines, because such servos are “bolted-on” to existing mechanical machine designs, the servos are inherently limited in the benefits they can offer in such applications.

Technology user groups like OMAC (Open Modular Architecture Controls) are working on ways to help machine builders migrate their designs to third-generation machinery, while helping machine buyers identify the different generations of packaging equipment.

The original version of this article was first published in the U.K.’s Processing and Packaging Machinery Assn.’s (PPMA) Jan./Feb. 2003 issue of Machinery Update magazine. Reprinted with permission.

For more on servos, download a PDF of our educational poster at: packworld.com/poster