Bottle Line 4 in Elkton, VA, the newest bottling line installed by Golden, CO-based Coors Brewing Co., was engineered and started up in a compressed time frame thanks in part to the efficient use of “data blocks” influenced by standards set forth in PackML.

Other notable attributes in the line include these:

• A new type of variable-speed drive mounted directly on the conveyors dramatically reduced the amount of wiring necessary and also helped accelerate installation.

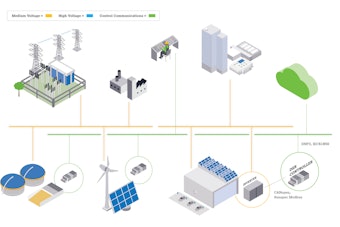

• Industrial Ethernet is used more extensively than in any Coors line thus far.

• Manufacturing Execution System (MES) software implemented on the line makes real-time data so accessible to operators that they are uniquely positioned to maximize throughput.

The MES software at the heart of the new line’s controls package lets data flow from a data historian to Coors’ Enterprise Resource Planning system. The data historian is like a flight recorder on an airplane. Its primary job is to collect time-related data from PLCs that reside on discrete pieces of packaging equipment. Then Coors needs to take that time-related data and add some context to it. This is what the MES software does. It turns the data into contextually rich information that an operator can act upon. For example, if the mean time between failure on a case packer is supposed to be 30 minutes but in actual operation it turns out to be 20 minutes, that hurts the efficiency of the line. If Coors monitors such things in real time, they can identify potential problems early and link them to quick-fix routines or other corrective action. It isn’t like Coors hasn’t done such things in the past, but this will deliver the information faster in a more sophisticated way. With this kind of improvement in real-time data acquisition comes better asset utilization and more cases out the door.

The MES software’s interface with Coors’ Enterprise Resource Plannning system brings added manufacturing efficiency, says senior manufacturing solutions manager Mike Pichler.

“Process orders are sent from ERP to the MES software,” says Pichler, “which cues that order up so that an operator can look at the screen beside a packaging machine and know when it’s time to make, say, 20ꯠ cases of Coors Light. Included is all the necessary information regarding glass, crowns, labels, and cases that will be needed. He then interacts with the MES software to say, ‘OK, I’m starting this process order right now.’ The MES software then keeps track of how many cases are really made and how much beer was consumed to fill those cases. And when the process order is complete, the MES software reports back to ERP regarding the actual production.”

Top floor to shop floor

Doug Gray, director of process control and manufacturing information systems at Coors, is a big believer in this kind of closed-loop, top-floor-to-shop-floor information exchange.

“The idea is to have a process order come down from ERP and have it automatically reconfigure the packaging lines,” says Gray. “Of course there’s a necessary pause to run out the previous order’s containers, and naturally there are certain mechanical adjustments that will be impossible to get away from completely. But what we’re trying to avoid is the need for operators to have to look up the next run and then take numerous steps to make the line ready for it. Things like the speed on conveyors or the pressure and temperature setpoints—the whole dynamics of the line. To the extent possible, these things should be derived from the process order that comes down from the ERP. And in the opposite direction, data on efficiency, downtime, and material usage is captured and sent back to the ERP.”

Gray’s vision is not entirely fulfilled by the new systems implemented at Elkton. But the smooth exchange of information does play a key role in making the line versatile enough to handle any one of six different bottle types: 40-oz, 22-oz, 16-oz, 12-oz long-neck nonreturnable, 12-oz returnable, and 7-oz. Responding to the next container size that comes down from the ERP would not be possible without knowing the real-time status of all the machines in the packaging line.

When asked what steps had to be taken by packaging machinery OEMs to permit the efficient flow of information that characterizes Bottle Line 4, Gray laughs a little wearily. “We’re still working on that,” he says. “The OEMs have to structure their code above the normal logic they provide so that this kind of data acquisition is possible. Getting them to do that isn’t always easy. What we try to get them to understand is that these are the tools manufacturers like us need today if we plan to stay in business. Nothing more, nothing less.”

The packaging machinery that Gray and his project team would like to see more of is the kind whose controller exposes data in an accessible way the minute it hits the plant floor. They don’t want their team to have to bolt something on top of the program that the machinery arrived with.

That’s where PackML (an OMAC standard that brings consistency to the definitions used for packaging machine states) and Make2Pack (an initiative sponsored by WBF and the OMAC Packaging Workgroup aimed at developing conceptual models and terminology for industrial automation that can be consistently applied to both processing and packaging) come in. “If these concepts and their emphasis on standards were embraced more widely by the OEMs, all this data exchange would come standard on the packaging machines we buy,” says Gray.

The bolt-on data block

On previous projects Coors created a series of “standard data blocks” for communication between the PLC and MES layers. As Coors gained experience with this type of communication, the data blocks were refined to reflect many of the PackML guidelines and still meet Coors’ needs. Coors and the line integrator responsible for the installation worked together to make sure these data blocks were used so that information was presented consistently to the MES layer.

The idea was to create standard data blocks for each piece of packaging equipment so that as soon as it arrived at the Elkton plant its PLC was able to expose its data to the data historian software in a recognizable way. According to Coors, these data blocks were influenced by PackML, though they don’t follow PackML guidelines exactly and contain some extensions.

One of the things that sets Bottle Line 4 apart from a controls integration standpoint is that its packaging machinery was designed to be ready to exchange data freely as soon as Coors plugged it in. In a more conventional installation, a data acquisition system is implemented after the line has been installed and started up. With a data acquisition system that is pre-loaded, the amount of time required for checkout and startup can be dramatically reduced.

Helpful in making this “plug-and-pack” scenario possible is that Coors standardized on a single controller for each piece of packaging machinery in the line. All the machinery OEMs were given the data blocks and the example PLC logic that drives the data block population so they could include it in their code prior to shipping their machines.

Locally mounted conveyor drives

Effective use of data blocks wasn’t the only contributing factor behind Coors’ ability to compress Bottle Line 4’s installation time frame. Also helpful was the use of a new breed of variable-speed drives mounted along the conveyors. Unlike more conventional AC motor drives—which are mounted in a remote control panel and connected by wire with the conveyor motors they drive and the sensors whose inputs govern the motors’ operations—these new variable-speed drives are mounted right next to their conveyor motor. Each drive has a lockable disconnect with four inputs and two outputs built in. Sensor wiring runs only a few feet to reach the locally mounted drive, rather than having to run all the way to a remote control panel.

By locally mounting the variable-speed drives, it’s possible to reduce I/O hardware and wiring, eliminate expensive shielded cabling, reduce wireway size, and dramatically lower electrical installation costs. The key to getting the physical drive hardware out of the remote panel and putting it instead out on the packaging line is the cabling system. The power to the drives is supplied by a new type of power cable. It’s a distributed power system that uses connectors to distribute 480-volt power. So rather than running individual power wires to each drive, you string a single cable along the conveyor length and connect the drives to it with the connectors. Two additional cables, one for DeviceNet and one for DeviceNet power, are also needed. But that’s it, only three cables running along the conveyors. At each drive there are three ‘Ts’: one for power, one for DeviceNet communication, and one for DeviceNet power. Not having to do all that wiring back to the remote control cabinet probably shaved considerable cost from the total installation.

As for Coors’ use of Ethernet on Bottle Line 4, it’s a reflection of a growing trend. Coors has four separate Ethernet networks. One is for control I/O, one for peer-to-peer communications from one packaging machine to the next, one is for MES—that’s the data collection layer where data is pulled out of the discrete pieces of packaging machinery to log downtime and throughput and efficiency and such—and one is for the normal office local area network communications, in other words, the ERP layer. The biggest benefit gained by using Ethernet so extensively is that it’s open and very common. Because it’s so well known, it brings easier maintenance, easier remote monitoring, and easier troubleshooting, says Coors.

With about five months of actual production on Bottle Line 4 now under their belts, Gray, Pichler, and the line integrator are working with Coors’ manufacturing optimization group to further improve the systems for this and future lines. All three are encouraged with the systems thus far and consider this a step in the right direction, although more work is necessary to achieve the expected efficiencies.

What’s really significant here, say Gray and Pichler, is that the project team practiced a form of concurrent engineering to compress the time frame needed to engineer, design, install, and put into production a complete new line.