Behind the scenes of a company that’s pioneering new and somewhat risky industry technology while growing beyond $100 million in annual revenue, Michael Senske hangs his hat every night and asks himself, “How could we have done it better?”

As the CEO and president of Pearson Packaging Systems, based in Spokane, Wash., Senske leads by example as his mindset of continuous improvement has transcended to the shop floor and beyond. From its people to its equipment, Pearson doesn’t rest on its laurels, which is most likely why the machine builder is appealing to companies like tech giant Amazon that needed an out of the ordinary solution to handle the unpredictable and everchanging e-commerce market.

Andrea Zaman, Pearson’s COO, will never forget opening an issue of the New York Times to find Pearson’s name on a Fanuc robot pictured in an article about how Amazon was deploying more robots to work alongside employees. But to her, that doesn’t mean Pearson has reached its peak; while Zaman and Senske celebrate and acknowledge milestones like these, the focus is always on what’s next and how they can optimize it.

“Growing from $20 million, when I first got here, to over $100 million now, you can’t just keep scaling the same way. You have to do it differently,” Zaman says. “And now, at more than 100, we’re again changing how we analyze our business and how we become scalable.”

As Pearson continues to scale, the OEM is prioritizing business initiatives that stand to propel their growth even further, and in some ways, potentially change the OEM business model altogether. With the company’s “continuous improvement” whiteboard full of new ideas from employees in all departments, Pearson is ready to ride the wave of whatever trend, industry or market that needs to be packaged and palletized.

Pearson Packaging Systems' facility: 180,000 sq. ft.

Pearson Packaging Systems' facility: 180,000 sq. ft.

Adaptation paves way for future development

Pearson Packaging Systems was founded in Spokane in 1955 with the invention of the first automated six-pack carrier erector. In 1994, the company expanded its facility to 110,000 sq. ft., which still serves as the headquarters. In 2002, the company shifted its focus from exclusively building machines to providing complete end-of-line solutions and then implemented lean techniques soon after in 2003 to improve quality and lead times for its customers. In 2004, the OEM began offering robotic systems, which positioned it for explosive growth. Four years later, Pearson went into acquisition mode, buying Goodman Packaging Equipment, giving them a presence in the Midwest as they kept Goodman’s Chicago office open with 20 project managers, service personnel and mechanical engineers. The company’s portfolio continued to grow with the addition of bliss/tray forming technology from Moen Industries in 2012. And most recently, Pearson acquired Flexicell, an Ashland, Va.-based robotics-only picking, packing and palletizing solutions provider, a move that will launch Pearson toward its next level of growth. While Pearson and Flexicell share similar product offerings, the companies didn’t share much customer overlap, but both stood a lot to gain by joining forces. Located in the Pacific Northwest, Pearson finds itself in a hard to reach place and also a little disconnected from the rest of the packaging industry. By purchasing Flexicell and leaving its operations in Virginia, Senske says he hopes to reach, service and support current and prospective customers more effectively.

The second most prominent reason behind the Flexicell acquisition revolves around Pearson’s dedication to offering robotic solutions. Flexicell was founded on the premise that it would solve packaging and warehouse automation problems with robots only, which was extremely appealing to Senske.

“Historically, we are more traditional machine builders, and although we had been integrating and implementing robots since 2004, we would always look at problems from a more traditional approach first and then apply robotics second,” Senske says. “Whereas with Flexicell, they were exactly the opposite. They wanted to solve problems from a robotic perspective only, and we thought that was healthy. We think that’s the direction the industry really needs to go because of flexibility, reliability, re-deployability and all those things that the robots offer.”

Pearson’s robotic offerings have also propelled the OEM into the e-commerce space, and with the addition of Flexicell’s approach to packaging applications, it will increase the OEM’s presence in the industry further.

“As an e-commerce company’s packaging or product styles are changing, we’re developing solutions that really leverage the flexibility and the re-deployability of robots, instead of more traditional approaches,” Senske says. “Another benefit of a robot is that there still might be some annual changeover, but you can automate large portions of the changeover process using robots. One online commerce company might have different needs than another, but at the end of the day, what we’re finding is that its automation process is very similar.”

Aside from conquering the e-commerce space, a large focus for Pearson in 2019 is ramping up Flexicell’s Virginia facility so that the OEM can better service the majority of its customers, which reside in the Midwest, East Coast, and Southeast. To manage the growth of the new facility, and two others, Pearson prioritized implementing an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, allowing all of Pearson’s employees—across multiple facilities—to see all of the OEMs projects.

Balancing LEAN with talent retention

To manage rapid growth over the past couple of decades, Pearson has implemented many LEAN techniques. In 2003, the company adopted LEAN manufacturing and have since developed a dedicated department with Six Sigma Black and Master Black Belts that lead a Continuous Improvement program with weekly meetings on the shop floor where people can pitch ideas and a group of managers evaluates and oversees immediate implementation. The department also leads anywhere from three to five Six Sigma projects at any given time and offers class instruction to all employees to facilitate the adoption of LEAN principles. Pearson also has a long history of running week-long Kaizen events to improve a large number of processes. Over the last decade, it has completed more than 65 official kaizen events. This year, Pearson was honored as the packaging leader in picking, packing and palletizing integration by FANUC America. Over the course of the past 10 months, Pearson has sold 110 Fanuc robots.

This year, Pearson was honored as the packaging leader in picking, packing and palletizing integration by FANUC America. Over the course of the past 10 months, Pearson has sold 110 Fanuc robots.

While LEAN has afforded Pearson success and growth, it didn’t come without hesitation from its people. When a company goes LEAN, there is a consensus that it means people and jobs will be eliminated, but Senske doesn’t view LEAN as a way to cut costs, he sees it as a way to drive growth. By removing as much non-value-added activity as possible, Pearson can increase its capacity, sell more equipment and handle more output with the same amount of people. It’s a win-win, which is why Pearson made a commitment that it will never eliminate a position as the result of a kaizen event. The company will redeploy that individual elsewhere.

“I have no doubt that not everybody is happy here,” Senske says. “Our growth, becoming an integrator and acquiring companies, can create a bit of angst. So I understand that there are times where people are stressed. Last year, we implemented a new ERP system, we integrated, we acquired Flexicell and we finished an office remodel. I would kind of jokingly walk into our staff meeting and say, ‘So what moron decided this was reasonable?’ We’re really fortunate to have really good people, and we really go out of our way to try to create an environment that retains them because we are only as good as they are.”

Back to the basics

When Senske came to Pearson 20 years ago from Microsoft Corporation, he envisioned the company focusing the product line, professionalizing the sales organization and realizing the ability to integrate complete end-of-line solutions. And Pearson has done just that.

“When I first came to Pearson, we were a much smaller company, and proudly proclaimed that we had 69 different standard products,” Senske recalls. “I think part of the problem we had back then was that we were really aligned around serving 10 key customers. So they would come to us every year and we would be really willing to do almost anything they asked. But we wanted to recast the company by focusing on what we were good at. Let’s actually look at what we’re good at, and then determine whether or not that applies to broader markets and a broader customer base, and just be really good at that for more people.”

So now, Pearson does fewer things—specifically case erecting, packing, sealing and palletizing—but for more people.

“As a result, I think the quality of our products is better,” Senske says. “Our customers just have a better overall experience.”

By focusing on its core competencies, Pearson was also able to recruit and train a sales force that knew the company’s equipment like the back of their hands but also understood the kind of industry Pearson deals in. Ultimately, bringing in more sales and customer relationships for the OEM.

“I want our sales force to communicate the value that we’re creating for customers. [I want them] to better understand what they need and then provide them that solution. It’s not just about the speeds and the feeds, it’s about how it’s going to help our customers solve a business problem.”

In Pearson’s Spokane facility, the OEM has taken part fabrication out of the equation due to the availability and abundance of machine shops in the Pacific Northwest, or the “land of Boeing." The OEM was adding the most value in the design, assembly and engineering of its equipment, so it decided to outsource part manufacturing to materials suppliers and vendors within Washington.

In Pearson’s Spokane facility, the OEM has taken part fabrication out of the equation due to the availability and abundance of machine shops in the Pacific Northwest, or the “land of Boeing." The OEM was adding the most value in the design, assembly and engineering of its equipment, so it decided to outsource part manufacturing to materials suppliers and vendors within Washington.

Pioneering new technology

While Pearson has now become an integrator, Senske says the company isn’t trying to be everything to everyone. Focusing its offerings on its core competencies has allowed the OEM to not only do what it does best, but it’s also given them opportunities to take risks on emerging technologies that have yet to impact the OEM space.

“I really underestimated how traditional of an industry this has been historically,” Senske says. “It’s taken a little bit longer than we thought it would reach some milestones, but I think over the last five years, we got the rock to the top of the hill, and now, it’s rolling downhill pretty quick.”

What does the rock represent to Pearson? Perhaps its blockchain, the technology that underpins cryptocurrencies—like bitcoin—but can also be used for other applications by providing a secure, decentralized approach to distributing digital information in a way that can be shared but not modified. It also has quite the potential to disrupt the current OEM business model.

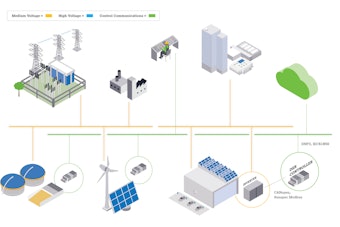

Pearson is currently piloting blockchain-based equipment, which will gather machine productivity parameters in real-time and use them to calculate transactional payments based on the machine’s overall performance. This Machine-as-a-Service (MaaS) model allows Pearson’s customers to get a machine up and running before they pay for the entire piece of equipment. The OEM has ventured into the MaaS model before blockchain technology existed, which meant the process was more manual. But now, implementing blockchain technology to this model has streamlined data collection and payment.

Learn more about who Pearson is Partnering with to provide blockchain-based machinery by visiting: oemgo.to/blockchain

“Instead of the customers feeling like they have to have onerous terms and conditions to force our compliance, we really believe blockchain potentially simplifies the contract because those terms and conditions really don’t apply anymore,” Senske says. “At the end of the day, they don’t have to worry about their down payment because there isn’t one. We’re providing them a completely different service than before that has a different financial and economic paradigm, and now there will be other terms and conditions.”

And while machine builders are already squeezed and pressured when it comes to handling payment terms from both its suppliers and customers, Senske thinks that blockchain-based equipment may put the power of cash flow and revenue back into the OEM’s hands.

This case sealer was tailor-made for the e-commerce industry in response to the demand for highly flexible equipment. Instead of having uniform sealers at the end of lines, Pearson will install a sealer like this that automatically adjusts to the different case dimensions that are coming at it on the fly. The sealer has many moving parts inside, the first checks the width of the box, the second checking the height, and there are photo eyes up front that will adjust the equipment to handle whatever it sees. Finally, the tape head will automatically adjust to accommodate the different box sizes. The first moving part checks the width of the box. And then this will check the height of the box.

This case sealer was tailor-made for the e-commerce industry in response to the demand for highly flexible equipment. Instead of having uniform sealers at the end of lines, Pearson will install a sealer like this that automatically adjusts to the different case dimensions that are coming at it on the fly. The sealer has many moving parts inside, the first checks the width of the box, the second checking the height, and there are photo eyes up front that will adjust the equipment to handle whatever it sees. Finally, the tape head will automatically adjust to accommodate the different box sizes. The first moving part checks the width of the box. And then this will check the height of the box.

“We will determine a certain amount of money per unit to measure with that particular customer, and they may look at that amount and say, ‘Well, wait a minute. If we just bought this equipment, it would be $100,000, but if we essentially lease this equipment for seven years, we could pay more than that. Why would we do that?’” Senske says. “But end-users will fundamentally have to step back and remember that they are not acquiring the equipment, we are giving them more flexibility, parts, service and delivering on a promise of throughput.”

During the pilot phase, Senske says Pearson is being very selective in who it works with so that the OEM can fine-tune its approach to find out how to benefit both parties equally. Once in place, throughput metrics could either be measured week by week or even down to second by second. And as Pearson’s equipment hits its goals, there’s going to be a continuous annuitized revenue stream because the invoicing and payment will be automated through the blockchain.

While this approach may provide Pearson with more flexibility and diverse revenue streams in the long run, what does that mean for its engineering resources that are dedicated upfront to building a piece of equipment that doesn’t pay them until after the machine is up and running?

“If you have the financial strength or wherewithal to get through that first year or two while you build that revenue stream, at the end of the day you’re going to have probably better and more consistent cash flow,” Senske says. “We are going to offer this service on a couple of our machines, not the whole business right away. It would be a problem if every single customer said they wanted to go to that model tomorrow. We probably could offer this because we are in a favorable position financially right now, but it would be a hell of a lot more risky than what we’re talking about.”

Pearson predicts five or six machines will be blockchain-based in year one, and maybe 15 to 20 in year two, but “who knows, it may take off even faster,” Senske says. The management and handling of Pearson’s blockchain-based machines will largely depend on the metrics and how customers want to measure them. There will be a code embedded into the machine’s PLC that will audit machine data periodically, which will then be substantiated by Pearson employees when a customer wants to validate that the machine is actually hitting its goals. In terms of the reconciliation of funds, a consistent connection to the machine where performance data can be transmitted and recorded is key. Pearson will also allocate occasional resources to help customers substantiate and audit the data and funds. Once the machine data is reported, the blockchain technology Pearson implements will work the rest out.

“We’re very aware of the fact that we need to further develop the model before we just open it up. We can’t be reckless,” Senske says. “But the feedback we’ve gotten from customers…a lot of people are clamoring for it.”

Looking forward

With 75 to 100 machine projects on the floor at any given time, it’s safe to say that Pearson is busy, but lowering its lead times are a major priority for the OEM in the near future. Right now, its core equipment has a 60-day lead time, which Senske and Zaman say they want to be lowered to 30 days or less, one year from now.

“It will no longer be that we’re competitive with lead times, it will be that no one will be able to keep up,” Zaman says. “We want to be able to say we have the best lead time in the industry.”

Going forward, Senske also thinks that Pearson needs to be less conservative in its approach to implementing new technology. The OEM’s future will be shaped by how well it listens to its customers, and how it implements operational adjustments to meet lead time expectations—not just within the obvious departments like engineering, assembly or supply chain, but also in marketing, HR, finance and IT.

“I think that we have a lot of opportunities in progressive technology, and frankly, we could also improve our service and support,” Senske says. “That’s one of the most important things we hear from customers…and no matter how good it is, it can always be better. We shouldn’t be satisfied if our customers are satisfied. We need to always push to be better and faster and create more value for our customers and the industry.