Multilayer, mixed-material flexible film packaging is a sustainability conundrum. Lighter in weight, using less material, and resulting in fewer greenhouse gas emissions than alternative packaging formats such as glass, aluminum, and rigid plastic, flexibles seem like the most eco-friendly packaging choice. But, unlike glass, aluminum, and rigid plastic, mixed-material flexible film* cannot be recovered at end of life.

For some sustainability diehards, the fact that the only place for multilayer flexibles at the end of their use is the landfill is a deal-breaker—despite all of their sustainability advantages. For those companies that supply and use this material, however, understanding the challenges associated with flexible film recovery and moving toward feasible solutions have become a priority, especially as the use of flexible packaging grows.

According to a 2015 report from PMMI, The Association for Packaging and Processing Technologies, “The unique benefits of flexible packaging have made it the second largest packaging segment in the U.S. [representing 19% of the total $164 billion packaging market]. The format has grown considerably in popularity over the last decade and has continued to take market share in the packaging industry.” It adds that while this growth may be starting to plateau, the market is expected to continue to expand at a healthy rate into the future. (Source: PMMI 2015 Flexible Packaging Market Assessment Report.)

Consulting firm Freedonia estimates in its 2015 study, “Converted Flexible Packaging,” that demand for mixed-material film packaging will rise 3.3% annually through 2019, to $20.7 billion, due to the cost and performance advantages of lightweight bags and pouches. In addition, it says that “converted flexible packaging’s source reduction, space savings, and lower production and transportation costs…will drive further conversions from rigid to flexible formats.”

Currently there are no systems in the U.S. to collect and recover multilayer flexible films. To put such systems in place will involve solving technical and commercial challenges at every stage of the process—collection, sorting, and end markets—with the development of each depending on the success of the others.

Drivers of change

While it is true flexible films represent a large chunk of the packaging materials market, their percentage of landfill waste does not: multi-material laminates accounted for just 1.6% of the total municipal waste stream in 2012, according to the Flexible Packaging Assn. Even though this number has increased since then and will continue to grow as the market expands, there are other pressing reasons why the packaging industry is taking on the challenge of flexible film recovery.

Alan Blake, Executive Director of PAC Next, a part of Canadian association PAC, Packaging Consortium, that was founded to create a vision of “A World Without Packaging Waste,” says the group initially became interested in finding ways to recover flexible films due to Canada’s Extended Producer Responsibility laws. Under EPR requirements, all stakeholders pay a fee based on the quantity of packaging materials they put into the market. PAC NEXT’s Multi-Layer Laminated Films & Bags project is focused on initiating and completing a pilot to recycle post-consumer recycled multilayer laminated film from a Municipal Recycling Facility (MRF).

“Given EPR, there’s this pressure to see what can be done to avoid materials going to landfill and what can be done to find solutions,” Blake says. “People become a bit emotional when they start seeing increasing levels of materials going into the waste stream that are non-recyclable, such as multilayer, mixed-plastic laminates.”

Jeff Wooster, Global Sustainability Director of Dow Packaging and Specialty Plastics, which is involved in many initiatives around flexible film recovery, explains the growth in interest in flexible film recovery this way: “The development of the recycling infrastructure for any material follows the introduction of that material and its growth to a scale where it makes sense to invest in a recycling infrastructure.”

For example, he says, when aluminum cans and PET bottles were first introduced, they were not recycled. But as the markets for these materials grew, recycling followed. “With flexible packaging, because it’s more difficult to mechanically recycle and because the weight of each individual package is much lower than it is for other materials, there are some additional challenges that other materials don’t have to the same extent.”

Consumer pressure is definitely also a driver, he adds: “Consumers don’t like to see packaging going into the landfill, and neither do we.”

One of the projects Dow is involved with is Materials Recovery for the Future, an initiative of the Research Foundation for Health and Environmental Effects, established by the American Chemistry Council. The project has brought together brand owners, manufacturers, and packaging industry organizations interested in creating recovery solutions for flexible packaging. Its first goal is to study the movement of films and flexible plastic packaging at U.S. MRFs.

“Our motivation for this is to close the resource loop and make sure that our materials continue to deliver value for as long as they can,” Wooster says. “We know it’s of great interest to companies, NGOs, and well-informed consumers to try to recover the value of their materials instead of putting them into a landfill.”

Collection: curbside or store drop-off?

The first step in any packaging materials recovery system is its collection from consumers. Single-stream curbside collection is available in many municipalities for a range of materials, including PET, glass, aluminum, paper, and cartons. Single-layer polyethylene bags, such as grocery, newspaper, and dry cleaning bags, are also collected for recycling through store drop-off programs. Currently, there are 18,000 locations across the U.S. that collect PE films. In 2013, 1.14 billion lb of PE film were recovered for recycling, according to the “2013 National Postconsumer Plastic Bag & Film Recycling Report,” from ACC.

Blake says adding multilayer flexible films to the materials collected through store drop-off systems is one option. “If you could get those materials together, then they are relatively easy to sort because of weight and density,” he says. “The plastic bags will just sort of float away. You could skim them off.”

However, he believes retail stores are somewhat reluctant to expand these programs due to fears about contamination and dirt. “Retailers are concerned about people bringing all this stuff to their front-of-store; they don’t want it to turn into a garbage dump,” he says. “You’d have to make a bigger effort in terms of defining areas where the material could be brought, making it clear to consumers, and keeping it clean.”

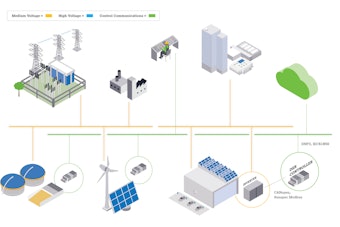

With current single-stream curbside collection in the U.S., consumers often mistakenly throw flexible films into the bin, believing that they are—or should be—recyclable. Once in a MRF sorting system, the two-dimensional flexible films play havoc with the MRF’s mechanical systems. “The material wraps around screens and other rotating equipment, it gets caught in places it’s not supposed to be, and it contaminates the paper stream,” explains Wooster.

Ultimately, the collection system adopted for flexible packaging will depend on the development of MRF sorting systems. “If MRFs had technology to adequately separate bags and not have processing problems, then the material wouldn’t be a contaminate, it would be a raw material,” Wooster days. “If we can implement technology that makes more of the things already in the bin into raw materials, we can ask for even more materials to be put into the bin. Then we can have a system with higher recovery rates.”

Sorting: technology available, but costly

Sorting technology for flexible films does exist—at a significant cost. The challenge is finding the most efficient systems and making them financially viable for MRFs. In order for MRFs to make the investment, there needs to be enough material collected, and viable end markets must be developed for the recovered material.

According to Blake, even if the challenges of collection are overcome, it will still take a lot of material to make sorting it worthwhile. “The recycling industry works on weight,” he explains. “To make a bale of flexible laminates, you need a ton of material. Just fathom this: To create a bale of rigids—and these are just approximate numbers—you need 10,000 containers. Since laminates weigh 80-percent to 90-percent less than rigid containers, you would need approximately 100,000 multilayer flexible laminates to make up that same bale, to achieve that same weight.”

In terms of end markets, because flexible films comprise a mix of polymers, there are currently no commercial uses for the recovered material. Said Nadine Kerr, Acting Manager of Processing Operations for the city of Toronto in a webinar sponsored by PAC Next, “Even when flexible film packaging is sent to a processor, it is difficult to recycle. Recycling is complicated, and it can yield a plastic with poor physical properties because it contains a variety of materials and is often contaminated with food.”

Before tackling the development of end markets, however, the Materials Recovery for the Future project is first trying to determine how flexible materials can be sorted. Dow initiated the project by commissioning Resource Recovery Systems to conduct a study to understand what it would take technically and financially to sort flexible films at a MRF. Upon completion of the study, Dow invited brand owners and packaging producers to join the project and drive it forward.

The first phase involves studying the movement of films and flexible plastic packaging through the MRF. So far, project members have gathered a representative assortment of flexible packaging present in the marketplace. These will be mixed with paper and other materials commonly found in a MRF and run through the sorting systems typically used for paper.

As Wooster explains, MRFs use modern optical sorters based on infrared technology that can identify the composition of the polymer types to sort 3D HDPE and PET bottles. “It’s not in use for plastic films or flexible packaging, however, but there are a few facilities that use this type of equipment to sort paper,” he says.

The hope is that the technology used to sort paper can be employed to separate out flexible films. “Paper is a two-dimensional object when it goes through the MRF, whereas a bottle is a three-dimensional object, so there’s quite a bit of handling and processing differences between the two,” Wooster says. “Flexible packaging and films though are two-dimensional like paper, so our hypothesis is that we’ll be able to use the sorting equipment that’s currently used for paper to sort the flexible film from the paper. What the project really entails is a series of experiments with equipment manufacturers and MRF operators to figure out how to use this equipment to properly sort the materials.”

Meanwhile, PAC Next has identified a company in Canada, TeTechS, that is using terahertz wave technology to sort different polymer types based on spectral signals. TeTechS has proved out its Rigel™ technology on a lab scale, but is looking for a venture capital partner to invest in the technology for commercial scale use. “This is an interesting sorting technology that might be the sort of thing that could help identify flexible films,” says Blake. “Then, using a sort of optical sorting air-blowing collection system, the materials could be shot into a recovery system.”

End-use markets: a range of opportunities

The development of end-use markets for recovered flexible films is really the linchpin upon which the rest of the recovery system depends.

One possible end market is energy recovery. This includes technologies such as:

Gasification, which converts feedstock into clean, synthetic fuel gas that can be used to generate electricity.

Engineered solid fuels, in which plastics and other waste is turned into fuel pellets to generate power.

Pyrolysis, a technology that transforms plastics into energy feedstock, such as industrial wax, lube stock, and synthetic crude oil.

Says Wooster, recycling options include a mechanical-type technology that allows the material to be turned into another article without changing the nature of the plastic, and chemical feedstock recycling, where the plastic is broken down into its chemical components so that the feedstock can be used to make other materials.

PAC Next is working to bring together industry partners to help advance technologies from Zzyzx Polymers and Greenable Technology. As Blake explains, the extrusion-like technologies allow PCR laminates to be reprocessed as is or as blends with virgin materials.

Zzyzx uses solid-state sheer pulverization technology to compatibilize resins and reduce and disperse contaminants. The end product is pellets that can be used in injection molding and compression molding to create new films.

Equipment supplier Greenable has developed a range of compounding extruder machines engineered to reprocess PCR laminated film, which can be used to manufacture products such as dimensional lumber.

PAC Next has done pilot work with both companies, but the biggest challenge has been collecting enough materials to run larger-scale trials.

Single-material laminates: a work-around

To circumvent the challenges of recovering mixed-material flexible packaging, some companies and projects are focused on designing multilayer films that use a single material, PE, or combinations of materials that can be collected through store drop-off programs.

In the U.K., the REFLEX project, led by Axion Consulting and co-funded by the U.K.’s innovation agency Innovate UK is working on designing new film constructions—in addition to helping develop a recovery infrastructure. “The aim of the REFLEX project is to create a circular economy for post-consumer flexible packaging,” explains Liz Morrish, Principal Consultant for Axion. “There are a number of key elements to the project, including the redesign of current packaging so that it is recyclable and investigating and optimizing technologies for sorting recyclable packaging from the waste stream.

“A key output of the project will be a set of design for recycling guidelines, to help brand owners, packaging designers, and convertors design flexible packaging that can be recycled.”

According to Morrish, over the last year, the REFLEX project has made significant progress in redesigning flexible packaging for food and household products to make them potentially recyclable, while ensuring the packaging structures and designs still achieve their required barrier and mechanical properties, and ease of handling on packaging lines.

Closer to home, Dow and film converter Accredo Packaging, Inc. recently collaborated to help launch a multilayer stand-up PE pouch for Seventh Generation’s dishwash detergent pods. Another reverse-printed multilayer PE SUP—which also sports a unique cube-shape—was designed by ConservaCube, LLC for Mountain View Seeds.

At least a decade away

Despite a multitude of challenges, there is a way forward for multilayer flexible film recovery, but it will not happen overnight. “It takes an awful lot of time to get the momentum and the critical mass to drive change through the packaging industry,” says Blake. “People forget how many decades it took to get decent systems in place for the recovery and recycling of PET. We would say that PET is a big success story. Yet if you look at the overall recycling rates even for PET, you’d argue that there’s significant room for improvement, but it’s taken decades to get where we are today with PET.

“Multilayer flexible films, despite their growth and despite the fact that they’ve been out in other regions of the world for some time, are still a relatively young packaging format in North America, so it’s going to take time to find solutions for these materials and find end markets, which by the way, unfortunately is still a challenge globally.

“I think it will probably be at least a decade before you’ll start to see the kind of investments needed to recover these films. I don’t think it will be any sooner than that.”

Says Wooster, “It’s really going to take a lot of people working together to solve this challenge. It’s not an easy challenge to solve, or it would already have been fixed, but we recognize that it’s important, so we’re committed to doing it.” c

*For the purposes of this article, “flexible film” or “flexible packaging” will be used to describe multilayer, mixed-material film—used for packaging such as stand-up pouches for snacks, petfood, beverages, frozen meals, and other products—versus single-layer PE film.