Editor’s note: Because of the sensitive nature of this topic, many of the interviews used were conducted under the condition of anonymity. The thoughts and opinions of many OEMs are reflected here, but many names are withheld.

The trend of large CPGs, pharma, and food and beverage companies extending payment terms, reportedly as an outgrowth of the 2008 downturn, isn’t news. From a mainstream perspective, The New York Times’ Stephanie Strom wrote about the trend in April 2015, Big Companies Pay Later, Squeezing Their Suppliers. And PMMI’s own Chuck Yuska has gone to bat for OEMs in various mainstream media editorials and opinion pieces.

“Late payments are squeezing small businesses that create almost 60 percent of new American jobs and employ half the workforce,” Yuska stated in a recent editorial in the Rochester Business Journal. “Late payments are also against these corporations’ self-interest: If these suppliers can’t hire, their productivity and innovation will stagnate. And if they shut down, prices will invariably rise.”

But for the OEMs themselves, the situation is most often related anecdotally, relegated to hushed tones over drinks at association meetings and trade shows, with suppliers bemoaning the lengthening state of payment terms. It’s difficult for an OEM owner to publically discuss, because if one OEM takes a stand, a competing builder may look more attractive to CPGs by comparison. It’s not a hill many are willing to die on, but they may die on it anyway. Suppliers are essentially floating loans to the extent of funding their customers’ projects—out to 180 days as one contract we saw suggests. The trend is becoming impossible for OEMs to bear, much less intentionally ignore.

CPGs risk hurting themselves

Because extended payment terms present an existential risk to OEMs in many cases, the negative impacts stand to come around to bite the very end users that have implemented these terms.

“In the long term as a customer, they’re going to be faced with limited choices, or declining innovation and solutions because of the suppliers’ inability to fund their businesses,” says Glen Long, SVP, PMMI. “Customers will have less choice in terms of number of vendors to choose from, and the innovative solutions that are coming from these members will be less if they’re less inclined to take this business.”

An engineer at one Midwestern OEM has seen this movie before. Coming from the automotive assembly field, he saw smaller automation houses pushed into unfavorable payment terms by the muscular “Detroit Three.” And when already long-tail automation projects were delayed, the negative cash flow became unfeasible for the suppliers, resulting in their shuttering or leaving the market.

A similar dynamic could befall OEMs, alongside their “big boy” customers. Leverage lies so heavily on the CPG side that OEMs are forced into one of two choices. One family-owned OEM explained how it walked away from a “huge client” due to that client’s intractability on unfavorable terms.

Another East Coast OEM went the other direction. “We have had to extend our window for them because those companies are not willing to budge. They set the rules, so we have to either be flexible to get the order from those big companies, or to just lose the order all together. They seem to have no problem walking away if we aren’t going to give them the terms they want,” he says.

The Midwestern OEM went on to cite different types of projects, and how some are more amenable to positive or neutral cash flow than others. But the differences in those project types portend something bigger for the industry as a whole.

“Payment terms are generally desired and intended to be at least cash flow-neutral,” the Midwestern OEM says. “Large or very custom systems with a high content of engineering should be more cash flow-positive due to risk inherent with custom projects. Likewise, standard machines that have a short lead time and that are not designed for a specific application allow us to be more flexible with payment terms.”

But such terms cause major distress to OEMs with comparatively few, engineering-heavy projects, per year. And in so many cases, those smaller, one-off, high-engineering-content jobs are the vanguards of real innovation that drive the industry forward. These are the innovations that stand to make CPGs more competitive. That being the case, OEMs say that CPGs aren’t doing themselves any favors with extended payment terms on such jobs.

“It hurts small/medium/big companies who pay their suppliers net 10 or net 30, like our company,” says Emmanuel Cerf, PolyPack, Pinellas Park, Fla. “We then become the financial institution for our customers.”

A playing field tilted toward foreign competition

Big CPG and food/beverage companies are managed by financial advisers, not the people to whom OEMs are directly selling. Those folks, sometimes engineers themselves, are often sympathetic to the OEMs’ plight. John Giles, Manager, Operations Engineering at Ada, MI-based Amway, is a good example. In response to a PP-OEM survey in which 42 percent of OEM respondents considered net 60 to be a fair payment window, he said:

“To me, the surprise is that [so many] said net 60 is OK. We went to a net 60 model two years ago and it was a disaster as far as the OEMs are concerned. It ends up being a procurement and negotiating thing for us,” he says. “But we take the first stab at that net 60 days and we’re responsible for that. If the OEM doesn’t deem that acceptable, then we let them deal with the procurement department. We get out of it at that point.”

The European Union legislated its way around this disconnect with the Late Payment Directive, an on-the-books 2013 EU law designed to safeguard smaller businesses from the long payment terms from their larger customers. As a collection of sovereign nations trading across borders, it only made sense, as over-border trade is notorious for creating extended payment term situations. The U.K. enacted its own version, the Prompt Payment Code. While nonbinding, it encourages reasonable payment terms.

“In the European Union, they abide by the Late Payment Directive, which requires public authorities to pay their suppliers within 30 calendar days of receipt of an undisputed invoice, matching the UK Government’s standard practice,” Yuska says. “In Europe, payment terms for business-to-business payments as fixed in the contract cannot exceed 60 days unless otherwise expressly agreed, provided that the terms are not ‘grossly unfair.’ Under the directive, the 60-day limit also applies where a public authority is carrying out ‘economic activities of an industrial or commercial nature’ by offering goods and services on the market. However, the U.K. has opted to keep the limit at 30 days for this type of contract.”

The Supplier Pay Initiative (called SupplierPay) was created by the Obama administration aiming to create an American version of the U.K.’s code. Created in 2014, it’s a similarly voluntary pledge, unlike the European binding legislation. But OEMs say SupplierPay has no teeth to bring companies to the table. Or worse, CPGs are coming to the table, but not fulfilling their pledge’s commitment.

While the roster of companies signing up for SupplierPay has grown from 26 in 2014, to 47 in 2015, the program has less than stellar results. Some stats say that more than half of the companies who originally pledged have actually extended their overall payment days, by a median of +1.9 days. Without legislative muscle, OEMs see this as a weak first step, and Yuska agrees.

“Sadly, all that appears to be window dressing,” he says. “Based on supplier reports, the situation appears to be getting worse in the CPG industry. Companies like Anheuser Busch-InBev, General Mills, CocaCola, and dozens of others continue to withhold payment for 90 and even 120 days upon delivery of services.”

In a letter to suppliers, a large CPG offered this rationale:

“A recent benchmark study confirmed that our current payment terms are significantly shorter than the industry standard. As a result, we have made our standard payment terms a minimum of net 60 days…”

Yuska worries that a multinational company adopting devastating late payment practices as “industry standard” clears the way for other companies to follow suit and force small and medium-sized businesses to carry the burden of extended payment terms. And it’s not like those companies aren’t in a position to pay, as many are sitting on piles of cash.

Cerf worries that the fact that big muscle can dictate an unfavorable business environment helps threaten American technology, as foreign counterparts can get government assistance to export equipment and therefore accept unrealistic terms.

“The industry has become a financial game instead of a technological enterprise,” he says. “The bottom line is that bankers do not produce anything, they just move money around to be able to keep a part of it.”

The aftermarket problem

Longstanding OEMs have thousands of machines in the field, and those machines are designed to last. But they won’t last without regular maintenance, and wear part replacement is a necessity.

If longer payment terms force builders out of the industry, or force consolidation, some OEMs point out that parts and service for existing machines will become more expensive, or of lower quality, if they can even be found.

One Southern OEM with thousands of machines around the world explained that in the course of a machine’s life, which can span decades, general operation requires fresh parts. Some of those parts are manufactured at the time of order. A CPG may have 50 machines from a vendor that he or she has to keep operating, 24/7. Without a steady, quality parts supply, that 24/7 operation may be interrupted.

“Would you shift your source of wear parts from the original equipment manufacturer, who designed the part to begin with, to, say China?” that OEM asks. “It could and does work for some parts, to be sure. But it’s also adding risk, both in availability and quality.”

Leveraging innovation

Donald Copertino, senior counsel at Becton Dickinson, a large pharmaceutical end user, is pushing for more innovation for his company’s pharma packaging lines and has been relying particularly on smaller OEMs for more unique, custom solutions. In working with these OEMs, the company recognizes that net 120 payment windows are not compatible with innovation. While larger OEMs can commit more manpower to multiple projects at once, smaller OEMs may only have enough people on the floor to handle one project at a time, putting them in a dangerous position if they were to take on a project with a long payment window. But the company says there is value in working with a smaller OEM, which makes it easier for the company and other multi nationals to be flexible to accommodate their terms.

“OEMs need to understand the payment terms they are getting are mandated by corporate procurement groups, and a net 90 or longer payment schedule isn’t uncommon for them. OEMs are designed to be innovators, and a lot of times, they can’t adhere to an unrealistic net 120 payment schedule because their cash flow doesn’t support necessary innovation,” Copertino says. “Our business understands that long payment windows are not reasonable for a small, nimble OEM that might have 10 people in the company. How can you wait a quarter before you get paid?”

Until help arrives, OEMs try to make it work

Though each OEM may have an exclusive and specific set of tactics relating to payment terms, PP-OEM found some general strategies to help mitigate friction for OEMs of all sizes.

Copertino urges OEMS to negotiate with end users and procurement groups. He says that he and other large multinationals willingly accommodate shorter payment windows for female- or minority-owned business, or family businesses.

“It’s definitely something that should be brought up during negotiation. Although there is no formal process in the industry for these small businesses to negotiate terms, if you don’t ask for shorter payment windows, you aren’t going to get them. But don’t spend six months trying to negotiate to meet in the middle. End users need to get their lines up and running quickly, so negotiations can be seen as a waste of time that they do not have,” he says.

Another tactic can involve making the end user pay more for longer windows. A second Midwestern OEM with whom PP-OEM spoke builds the cost of long payment windows into their terms to get customers to agree to shorter windows.

Cerf agrees with that tactic. “What our customers do not realize is that they are paying more for our equipment than if they respected net 30 days terms. Our cost of operation is much greater as, in turn, we have to finance our R&D and/or growth. For example, we have had to secure a loan to add 24,000 sq. ft. of production area. If all of our customers paid us net 30, we could have paid cash, but instead the cost of the loan will ultimately be added to our equipment costs.”

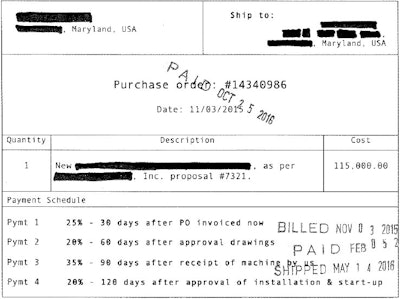

In another effort to level the playing field further, OEMs can use the “proof of principle” method as a tool to reduce and manage technical risk and demonstrate feasibility. Set a payment schedule that specifies events and milestones with payments that should follow. These milestones could include the initiation of purchase, design reviews, fabrication of a system, factory acceptance testing, site acceptance, or delivery of final documentation. However, OEMs should avoid disclosing the cost of specific events, like purchasing machine components, in the schedule.

“Procurement groups will try to disassemble your bid where you are telling them why a certain amount is going to components or other factors, and they could come back and say, ‘That is too expensive.’ Instead of allocating money for what those components cost, focus on when those components are purchased and put into the system and what milestone you can classify that as,” Copertino says.

Other OEMs introduce incentives into schedule milestones. Incentives and penalties may also help both parties adhere to terms, conditions, and schedules more closely.

“We have bonuses for early deliveries and penalties for late deliveries. We offer both the carrot and the stick because we have to hit the schedule right on target. Developing the schedule together during specifications is extremely important and allows you to create these incentives,” Copertino says.

When developing a unique payment schedule, assign different payment terms for different milestones to mitigate longer payment windows, for example, a net 10 window for the upfront payment may provide the OEM with more cash flow, faster.

“If we are working with a longer window than net 60, most of the time, we end up settling on a larger down payment to counter it,” one OEM said.

In contrast, the East Coast OEM says the biggest challenge in dealing with its customers is landing the company’s standard, initial payment of 40 to 50 percent down before product initiation. That OEM says there is a lot of pushback to make that initial payment as small as possible. The OEM has had end users asking for as little as 10 percent to get started.

Beyond negotiation tactics, a sure-fire way to ease payment window friction points is something most OEMs are already doing.

“Once you have established a relationship with an end user, it makes contracting easy. There is value to an end user in knowing that you are a valuable OEM supplier,” Copertino says. “As you develop relationships over time, those terms could relax a bit to help your company be much more effective.” pw

The ethics of extended payment terms

Guest editorial source withheld

Editor’s note: Due to the sensitive nature of this article, many who wanted to speak on this topic weren’t able to. PP-OEM received the following editorial submission on the topic, and we’ve chosen not to identify the author.

It wasn’t that long ago, in 2007, when terms were typically net 30. And if someone asked to extend payment terms, there would be whispers that something must be wrong at that company, or that it must have a cash flow problem. But now, less than 10 years later, it has become acceptable to extend terms for, from an OEM’s perspective, no reason at all.

We haven’t mentioned ethics and integrity in this conversation. All of the largest CPGs have pages on their websites outlining their vision, values, code of ethics, codes of conduct, and their overall concern for the world around them. A few examples include the following “enduring commitment to integrity, ethical performance” or “basic ideas of fairness, honesty, and concern for individuals and society” or “adhere to the highest ethical standards of conduct…Integrity is and must continue to be, the basis of all our business relationships.”

How is it fair and ethical to expect a smaller company—less than $100 million in revenue—to finance the capital equipment purchases of a much larger one of maybe $20 billion in revenue? Where is your integrity when you stretch payment out 120 days without regard for the trickle down effects this has on small business or the economy as a whole? The economic reasons for this shift in payment terms (some count 2008 as the culprit) are not affecting the CPGs’ cash flows now, as most are sitting on large amounts of cash. Yet they have doubled-down on squeezing their suppliers even more (we’ve seen payment terms extend from net 30 in 2007 to net 120 days in 2016), all while touting their ethics and fairness. It is very short-sided of these largest of the large; it’s the wrong thing to do. It’s unethical, irresponsible, and is directly affecting the economy, for the benefit of the few.