Has the bloom gone off the Retail-Ready Packaging rose? Are Consumer Packaged Goods Companies reluctant to expand RRP because they don’t see a clear path to an acceptable ROI? Are purchasing departments pushing back as they realize that a retail-ready shipper holding a dozen units might cost 20% more than a brown kraft RSC holding the same amount?

The short answer to each question is no and yes. In other words, the amount of packaged goods reaching consumers in RRP formats continues to grow. But at the same time, certain observers of or participants in the value chain are beginning to say that effective RRP initiatives that bring benefits to all are not that easy to come by. Consider, for example, this discussion question posted to the LinkedIn Packaging World Group by Wally Petrac, vice president of sales at Pearce Wellwood, a full-service display company specializing in design, printing, co-packing, and delivery of point-of-purchase solutions.

“Is Retail-Ready Packaging still viable? Back in 2009 there was quite a push by Canadian, and later U.S., retailers towards Retail-Ready Packaging. After many CPGs found it difficult to find reasonable ROIs, there seems to have been a slow down in RRP implementation. What have any of you seen or heard?”

Among the comments posted in response was one from Thomas Ciecorka, a packaging engineer, structural designer, and project manager consultant. He observes that while Walmart and Loblaws Canada are still moving forward, the only true believer in the U.S. is Aldi. “The U.S. is not moving ahead quite like in Europe,” notes Ciecorka. “Kroger was moving ahead with its store brands until they found out the cost. They have slowed progress and are looking at only certain items. Walmart is trying to go ahead in the U.S., but many store managers are pushing back, and some in Walmart do not see the savings in the U.S.”

Ciecorka also believes that from an execution standpoint, while the best solution is a proper display tray from which a perforated brown kraft top has been removed, too many companies are settling for a standard brown kraft RSC with a perforation bolted on. This, in his opinion, leaves much to be desired where presentation is concerned. It’s too much of a hybrid as opposed to being something designed to accomplish specific goals in the value chain. He adds that, unlike the European marketplace, no one in the U.S. wants to pay for graphics on RRP. His summation: “The CPGs I have been working with have not embraced RRP. They are preparing for it, and they have done some items, but they are fighting tooth and nail all the way.”

Hormel’s approach

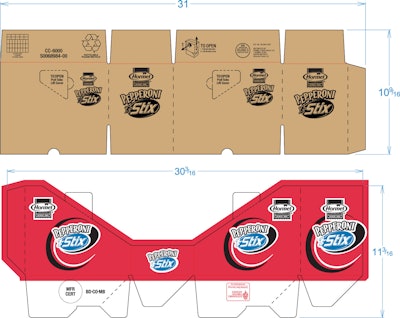

While Ciecorka’s observations about CPGs apply in some cases, they don’t appear to ring true where Hormel is concerned. The Austin, MN, food giant recently adopted a retail-ready display case for pouch-packed Hormel Pepperoni Stix holding five or six individually-packaged dry sausage stix. Twelve of the pouches are placed in the display case, and the cases are palletized 34 per layer and five layers high, for a total of 170 cases/pallet.

This is no brown box with a perf bolted on. It’s an RRP that is carefully and specifically designed to function optimally from point of manufacture to the moment when the consumer picks a primary package or two from the attractive red display tray.

According to Hormel, the price of this case is slightly higher than a standard RSC due to the extra manufacturing process of combining the top and bottom together at corrugated manufacturer Minnesota Corrugated Box. The corrugated manufacturer even had to invest in new equipment to produce this style of display shipper. But Hormel believes that developing this shipper was the right thing to do for several reasons:

• This design reduced the potential for ergonomic issues at Hormel facilities by reducing the number of motions and steps it takes to assemble each case.

• The new display shipper eliminates the need for retailers to use a box cutter to get into the case, so their job is safer.

• The Hormel plant was able to eliminate one inventory of boxes; now that the display tray and cover come glued together, Hormel does not have to stock and manage both cover and display tray inventories at their facility.

According to Hormel, the move to the display case was a Hormel Foods initiative. “It was a collaborative effort among our corrugated supplier, the plant, operations, purchasing, and the R&D packaging group,” says Chad Donicht, senior packaging engineer at Hormel. The two pieces of the display case are combined in one pass to produce a flat blank with an auto bottom and RSC top. At Hormel, these are opened and filled by hand.

The specialty folder/gluer that MC Box uses to make Hormel’s two-part RRP is the Turbox/Top Matcher from Bahmueller (www.bahmueller-usa.com). A sheet-fed machine capable of 10,000 units/hr, it was installed last year, says MC Box President Tim Krebsbach.

In this application, the sheet fed into the Bahmueller that becomes the red in-store display tray is a 32-lb ECT E-flute whose clay white linerboard is printed flexo in three colors. The sheet that becomes the removable top is a 32-lb ECT B-flute whose brown kraft linerboard has one-color flexo printing that includes opening instructions for store personnel. The two are folded and glued in a single pass.

“We’re combining two pieces in this case, but the Bahmueller is capable of joining three pieces if you wanted,” says Krebsbach. “For example, you could add a structural support like a bottle divider in the package. It’s also capable of handling not just corrugated but paperboard, too. This container’s bottom, for example, could have a 20-point folding carton stock.”

Servo technology is the key

Krebsbach appreciates the ability of the Bahmueller machine to join multiple substrates into one shipper. He says that servo technology is the key. “An older system relying on chains and belts and gears would have too much give,” he points out. “This is a very exacting process that can only be done with servos.”

MC Box’s investment in such equipment reflects management’s belief that more RRP business is on the horizon. But Krebsbach stresses that the investment in such a machine can only pay off if the machine is used to produce a certain kind of customer order. “Because set-up time is anywhere from one to four hours, depending on the job’s complexity, we look for high-volume jobs that repeat,” says Krebsbach.

Hormel’s Donicht believes that packages like these are good for both Hormel and the retailers who are on the receiving end. “Both groups want to make their employees’ jobs easier, safer, and more efficient. They also want to increase consistency of product displays and increase sales of products while being profitable.”

Donicht says that Hormel sees the most success with RRP when both parties—Hormel and the retailer—collaborate during the design process and are flexible on display counts. Ideally, the design should

• not be too complicated for store or plant employees to execute properly

• be cost-effective yet robust enough to protect the product during transit

• be effective for the retailer’s desired location and movement throughout the store

Also, machineability and operational efficiencies are essential to make RRP work, says Donicht. “Depending on the production quantities required and the shelf-life of the product, it might not even be feasible to produce the RRP if we can’t pack it out quickly enough,” says Donicht.

As for display counts, too few units cause the cost to be very high for the extra labor and materials needed to produce the RRP, says Donicht. On the other hand, if the number of units is too high, the store can’t sell through in a timely manner. If the retailer sets a hard count for the number of consumer units in the RRP, it’s possible to miss out on opportunities to improve shipping efficiencies, pallet utilization, or the opportunity to see a better design that has a slightly different consumer unit count.

Standard vs. premium

Sometimes the RRP approach taken by a CPG company is shaped by where the product sits on the standard-to-premium continuum. At Bumble Bee Foods, for example, the RRP format for a standard brand of sardines may not be much more than shrink film around a dozen tins of sardines or tuna. The premium King Oscar brand, on the other hand, gets the more lavish treatment shown on page 84: a display tray format made of E-flute corrugated printed flexo in three colors plus varnish. It’s manually assembled and semiautomatically filled and closed in a plant in Poland. Each tray holds 12 tins, and each tin is wrapped in flexible film.

Brian Stepowany, packaging development manager at Bumble Bee Foods, emphasizes how important it is to be careful about costs in designing for RRP. “Look at any RRP manuals put out by Kroger or Walmart and you’ll quickly see they are asking for white linerboard. Anything but brown kraft looks good on the store shelf from a display standpoint. But when you go from brown kraft to white linerboard, right off the bat you’re looking at a cost increase of about four percent.”

The other thing that must be kept in mind are the limitations of tray-forming and packaging machinery, says Stepowany. The typical tray format in RRP includes a prominent front facing. If a packaging line’s tray assembler isn’t geared for that, it can be a problem. In the case of the King Oscar RRP shown here, he adds, such considerations are not an issue because these are set up by hand and loaded by hand.

Another packaging machinery line issue, adds Stepowany, revolves around lot and date coding. “A line may be set up for ink-jet printing on a simple brown kraft tray sidewall,” he observes. “If you modify the shape of that sidewall for RRP purposes, or if the linerboard is glossy paperboard rather than brown kraft, you may find yourself needing a bunch of new equipment on your packaging line. But you can’t just run out and spend millions of dollars on new machinery, nor is it easy to outsource the RRP portion of your output to a contract packager without introducing cost issues.”

RRP should try to be plant and production friendly, says Stepowany. “We can’t afford to start affecting line speeds negatively. If my can of tuna that retails for 97 cents is doing 56 cycles per minute, I can’t afford to have a newly designed tray that runs at 40. So at Bumble Bee I’ve been trying to communicate these in-plant realities to sales and marketing. The goal is to prevent us from agreeing to things that we can’t then produce profitably.”

So where is RRP headed as we look to the future? According to MC-Box’s Krebsbach, there seem to be two philosophies.

“When purchasing departments look at multiple passes on the box-making machine and the use of white linerboard instead of brown kraft, they see a 20% increase in cost and begin to question the validity of a shipper like the one Hormel uses for Pepperoni Stix,” says Krebsbach. “On the other hand, marketing departments are continuing to push RRP. Retailers are, as well. In fact, you now have Tesco in the U.S., and they know how widespread and successful RRP has been in the U.K. So I think the philosophy that is in support of RRP will win out.”

Bumble Bee’s Stepowany agrees.

“Yes, I see RRP continuing to be a front runner in the packaging scene, alongside of productivity optimization and sustainability,” says Stepowany . “What I’m trying to do is working more closely with operations and the capital budget to make sure that if we’re looking at buying new equipment it’s conducive to RRP type designs. Why buy a new machine capable of doing the same 13⁄4 inch sidewall trays? It should also be able to do a tray having a 3⁄4 inch lip and die cut panels on it while not requiring us to sacrifice any cycle time.”