Introduction

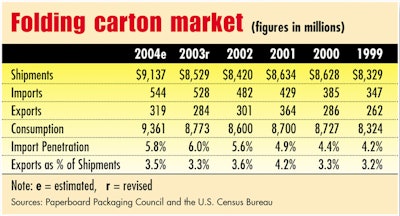

A group of executives at U.S. paperboard packaging companies, known as the Paperboard Packaging Alliance (PPA), raised this question: How can paperboard packaging create more value for consumer packaged goods companies? The PPA enlisted consultancies Packaging Technology & Integrated Solutions, Kalamazoo, MI, and New Product Works, Ann Arbor, MI, to help find out.

Two years of research—consumer focus groups, interviews with brand managers and store managers, and independent observations in stores—determined that significant growth opportunities exist for paperboard packaging. But suppliers and consumer product manufacturers must do a better job of creating packaging that complements contemporary consumer lifestyles and addresses retailer preferences.

In this second article of a continuing series, Packaging World looks at the shift from cost-based to value-based packaging, the visual and structural cues that consumers and retailers equate with value, and strategies for maximizing paperboard’s impact in signaling value.

Consumers crave convenient products that simplify and accent their lifestyles. Retailers demand shelf impact, product security, and customization. The term that best describes each of these desires is “value,” and both consumers and retailers point to paperboard as a packaging material they would like to see used more frequently—and effectively—to deliver it.

They told independent researchers recently that paperboard packaging offers under-explored potential for providing value in ways that matter to them. The possibilities include improving visual communications about product benefits on paperboard packaging’s expansive “billboard” and creating packages that double as the product delivery system while increasing product security.

Marketers and paperboard packaging manufacturers can answer these challenges—and improve sales—by rethinking their approach to package development. They should integrate the entire value chain so the best solutions can be assessed and adopted at the earliest stages of design. This process provides the best chance for creating a package that works through operations, distribution, at retail, and in the consumer’s hands.

This conclusion comes from consultancy Packaging & Technology Integrated Solutions (PTIS), which conducted an ambitious research project for the Paperboard Packaging Alliance. PTIS also brought in NewProductWorks (NPW) to assist in conducting consumer and retailer research during 2003 and 2004. The PPA is a joint initiative between the Paperboard Packaging Council and the American Forest & Paper Association.

During the research, each of the packages that consumers and retailers identified as those that really work for them were rooted in this equation: Product value = benefits/price vs. competition.

A value instead of a cost

Simply stated, the equation summarizes the belief of today’s consumer that the product and the package are one and the same, explains Brian Wagner, vice president at PTIS. Marketers at the forefront of this shift in thinking are responding with packaging that has shifted from cost-based to value-based. In this view, consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies treat packaging as part of the value rather than just a cost of goods sold.

The goal is still to keep costs low. However, this is not an absolute requirement when it comes to producing value-based packaging. When packaging simplifies consumers’ lives or solves a problem for them, they don’t mind paying a little more at retail, as long as the packaging makes the benefits clear to them.

How can paperboard packaging deliver more effectively on the value equation? Wagner recommends that marketers and paperboard materials manufacturers study consumers as both product shoppers and product users. The shopper in them wants packaging that helps them evaluate product differences and benefits and that makes them feel connected to a community of people with similar interests. The user side desires packaging that saves time, provides convenience, and inspires confidence that they can use the product properly.

On the retailer side, value-based packaging protects against theft, helps reduce labor costs, and directs consumers quickly to the right product on orderly shelves. It turns lookers into buyers and instills the trust that leads to repeat business.

Store managers and associates interviewed during the research said paperboard trays can improve the visuals in communicating product value, especially in pallet displays, which are prevalent with club stores and some mass merchandisers. Paperboard packaging, among other pluses, can give their freezer cases more graphic intensity and order, provide a better delivery system in pharmaceuticals, and heighten the graphic pizzazz in consumer electronics goods.

The value gap

Too often, a gap exists between what consumers and retailers want from paperboard packaging and what appears on store shelves. Steve Levkoff, president at Standard Folding Cartons, believes one reason is that packaging manufacturers in general spend too little time talking directly with consumers.

“We need to spend more time with consumers and with package designers,” Levkoff says.

Wagner believes the gap exists for a second reason: Few marketers ask their packaging suppliers how to achieve value.

“Marketers generally don’t see the value in talking to suppliers. They see package development as a more linear exercise,” he says.

In a linear approach, a brand manager develops a product concept. The Marketing Department takes the product to Engineering with the directive that “we need to put the product in a box.” Marketing then asks the Purchasing Department to solicit bids from suppliers to make the box. But too often, Purchasing focuses solely on cost and doesn’t understand the value equation.

One weakness of the linear approach, as it pertains to paperboard packaging, is that converters and raw materials suppliers of paper products are often brought into package development too late to introduce ideas for creating value-based, innovative packaging that works on all levels, Wagner says. As a result, consumer goods companies too often emphasize how their product tastes and performs over how it’s delivered to the consumer. They’re not thinking through the overall imagery that a package can create, he adds.

Levkoff supports this assessment. “There are very few marketers who bring us in and allow us to enter the value chain early enough,” he points out.

Allan Boyle, head of creative design for Nestlé global brands, agrees that marketing and paperboard packaging manufacturers need to integrate more effectively. Speaking at the Paperboard Packaging Council’s annual spring meeting, Boyle said the paperboard industry should avoid “seeing things only as you see them. Instead of thinking like board manufacturers, think about what you can do for the consumer.”

Maximize every inch of a carton or container to sell the emotion in a brand and encourage consumers to rationalize that emotional impulse as they make product selections, Boyle says. When a distinctive shape using paperboard is not possible, the graphics need to be superlative to compete on the shelf, and success requires combinations of the right materials. One tactic is incorporating “smart” technologies into a carton design to create an interactive package (see oven box item on page 15 for an example).

A cat’s meow pantry pack

The principles of selling the emotion while providing a highly functional package are evident in Nestlé Purina PetCare Co.’s Friskies 12-can variety pack. Nestlé wanted a pantry pack that would protect and deliver 12 cans of cat food without damaging the package. The pack also needed to provide a high-impact front panel on store shelves and then function as a convenient dispenser unit in the consumer’s hands. It also had to hold up in high-speed mechanical filling processes.

Caraustar Custom Packaging Group used .022 solid unbleached sulphate (SUS) board for tear strength in designing a carton to break apart and allow consumers access to the product while storing neatly in the pantry. A lift flap on the main front panel tears away using j-cut perforations that expose the middle section of the carton. The rear panel features a cut-crease that engages when consumers break open the carton to expose the cans.

In Boyle’s view, “appetite appeal” now ranks second behind branding in packaging communications for food and beverage products. Offset printing in up to six colors on aqueous-coated board delivers the graphic intensity on the Friskies pantry cartons that says “buy me.”

Wagner says paperboard packaging manufacturers can engage earlier in package creation by taking the initiative to bring innovative ideas for value-based packaging to CPG companies. “You have the technical options that they didn’t even know existed,” he says. “There’s no reason why a marketer would know. It’s not their job to know.”

Paperboard packaging manufacturers can succeed in this proactive approach by anticipating their customers’ needs, Wagner says. Conversely, consumer goods companies should align themselves with manufacturers that work ahead of the curve.